You can't just walk into Rao’s restaurant in New York. Seriously. Don't even try calling for a Friday night reservation at 7:00 PM because the person on the other end—if they even pick up—will probably just laugh. It’s not because they’re mean. It’s because every single table in that tiny East Harlem joint has been "owned" for decades.

It’s a bizarre setup.

Basically, the seating at Rao’s operates like high-end real estate or a season ticket at Madison Square Garden. If you "own" a table on the second Tuesday of every month, that’s your table until you die or decide to give it up, which almost nobody ever does. This is why it’s often called the most exclusive restaurant in the United States. It only has ten tables. Ten. In a city of over eight million people, that’s a statistical impossibility for the average diner.

The Myth and the Meatballs

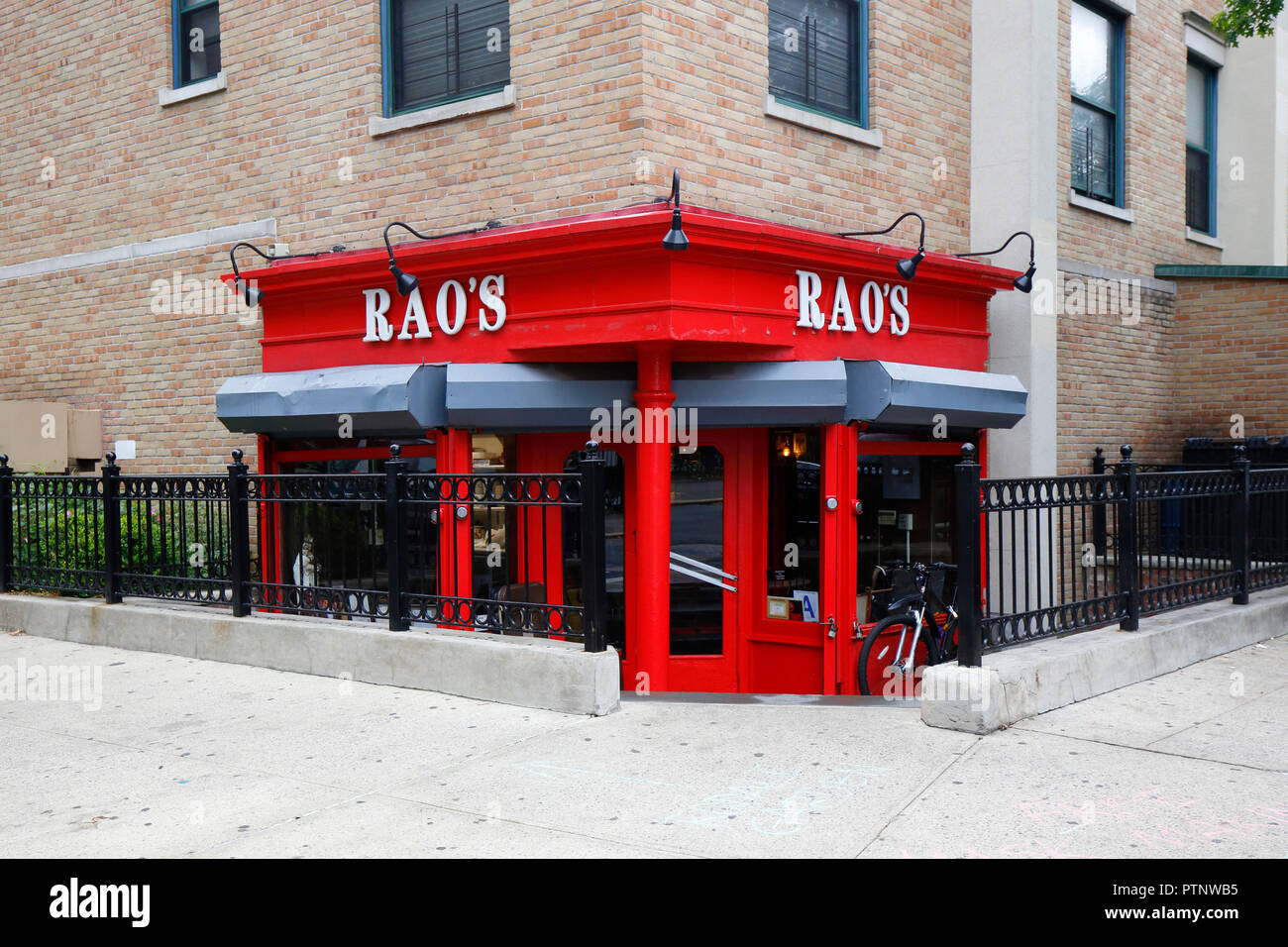

Located on the corner of East 114th Street and Pleasant Avenue, the red-awninged storefront looks like a thousand other old-school Italian spots. But inside, it’s a time capsule.

The walls are covered in photos of people like Billy Joel, Hillary Clinton, and Leonardo DiCaprio. It’s cramped. It’s loud. The jukebox is legendary. Frank Pellegrino Sr., the late owner often nicknamed "Frankie No," earned that title by telling almost everyone "no" when they asked for a seat. He was the gatekeeper of a very specific kind of New York magic that feels like it’s disappearing.

What makes Rao's restaurant in New York so fascinating isn't just the difficulty of getting in; it's the fact that the food is actually good. Usually, when a place is this famous for being exclusive, the kitchen slacks off. Not here. The meatballs are the size of baseballs and somehow stay light. The lemon chicken is bright and acidic, cutting through the heavy atmosphere of wood paneling and Christmas lights that stay up all year round.

Why the "Table Rights" System Exists

It started back in the 70s. A local critic gave the place a glowing review, and suddenly, the neighborhood regulars couldn't get a seat in their own hangout. To protect the people who had been coming for years, the family started the "residency" system.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

It sounds unfair. It probably is. But in a city that changes every five minutes, there’s something weirdly comforting about a place where the same guy has sat in the same chair every Monday night since 1978. It’s about loyalty, not just money. You can’t buy your way into a permanent table at Rao’s. You have to be "of" the family, or at least close enough to someone who is.

Bo Dietl, the famous private investigator, is one of the guys who has a table. So do various titans of industry and neighborhood legends. If they can’t make it, they don't just leave the table empty. They give it to a friend. That is the only way a "normal" person ever gets to taste the seafood salad. You have to know a guy who knows a guy.

Beyond the East Harlem Corner

Because the demand was so insane, the brand eventually expanded. You can find Rao's in Las Vegas and Los Angeles now. These locations are great, and they’re much easier to get into, but they aren't the Rao's. They lack that specific, heavy air of history that hangs over the Harlem original.

Then there’s the sauce. You’ve seen the jars in the grocery store. They’re expensive—usually $8 or $9 a pop.

Honestly, it’s one of the few celebrity-chef products that actually lives up to the hype. When the family started selling the sauce in the 90s, people thought they were "selling out," but it was a stroke of genius. It allowed the brand to become a household name without diluting the exclusivity of the physical restaurant. If you can’t get to 114th Street, you can at least have the marinara in your kitchen in Ohio.

The Culture of "The Room"

When you’re inside Rao's restaurant in New York, the rules of the outside world sort of stop applying. It’s not about being fancy. It’s about being "in."

💡 You might also like: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

There are no menus. The waiter—who has probably worked there since the Bush administration—will just tell you what they’re cooking. You eat what they bring. Usually, it’s a parade of antipasti, then the pasta, then the heavy hitters like the veal parm or the steak pizzaiola.

You’ll see a billionaire sitting next to a guy who grew up three blocks away. They’re both singing along to "My Way" on the jukebox. It’s a performative version of New York that shouldn't exist anymore, yet it survives because the gatekeepers refuse to let it change.

Misconceptions About Getting a Table

People think there’s a secret phone number or a bribe that works. There isn't.

I’ve heard stories of people offering five figures for a single night at a table. The answer is still no. The only real "hack" is charity auctions. Occasionally, a table owner will donate their night to a high-end charity gala. These lots can go for $20,000 or more, often including a dinner for four or six. That is literally the only price tag you can put on a reservation.

Otherwise, you’re looking at the "waiting for a death" strategy. When a table owner passes away, the "rights" usually stay within the family. It’s inherited like a rent-controlled apartment or a vintage Rolex.

The Impact of Frank Pellegrino

Frankie No was the heart of the operation. He was an actor, too—you might recognize him from Goodfellas or The Sopranos. He understood that Rao's wasn't just a restaurant; it was theater.

📖 Related: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

He treated the regulars like royalty and the celebrities like regulars. After he passed away in 2017, many wondered if the restaurant would lose its soul. But his son, Frank Pellegrino Jr., has kept the engine running. The policy remains the same. The lights are still up. The meatballs are still huge.

How to Experience Rao's Without a Connection

If you are dying to experience Rao's restaurant in New York but don't have a "table" or a cool $20k for an auction, you have to get creative.

First, follow their social media and look for pop-up events. They are rare, but they happen. Second, go to the Las Vegas location at Caesars Palace. The vibe is different—it’s much larger—but the recipes are identical. They even tried to recreate the "room" feel in certain sections.

But if you want the true Harlem experience, your best bet is to become a regular at the bars where the table owners hang out. It’s a long game. It involves a lot of negronis and a lot of listening. Eventually, someone might say, "Hey, I can't use my table next Thursday. You want it?"

That is the "Golden Ticket" moment.

The Actionable Reality of Rao's

Most people read about Rao's and get frustrated. It feels elitist. But look at it differently: it’s one of the last places on earth that hasn't been conquered by an app. You can’t use Resy. You can’t use OpenTable. It’s a human-to-human business in a digital world.

If you’re planning a trip to see Rao's restaurant in New York, here is the realistic way to handle it:

- Do a drive-by: Visit the corner of 114th and Pleasant during the day. It’s a historic neighborhood with incredible architecture. Just seeing the facade is a pilgrimage for foodies.

- Buy the cookbook: Seriously. The Rao's Cookbook is legendary. The recipes are surprisingly simple. The secret is the quality of the tomatoes and the patience of the cook.

- The Sauce Test: Go to the store, buy a jar of the Rao's Homemade Marinara, and compare it to any other brand. You’ll see why they were able to build an empire off a ten-table room.

- Check the Charity Circuit: If you have the budget and want to support a good cause, keep an eye on New York City police or fire department benefits. These are the most common places where a Rao’s dinner is auctioned off.

Rao's isn't just a place to eat. It’s a piece of New York City folklore that refuses to die. While other legendary spots like Luger’s or Kat'z are accessible to anyone with a credit card and a willingness to wait in line, Rao's remains the final boss of New York dining. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the best things in life aren't for sale—they’re for the family.