New York City’s subway is basically a giant, metallic organism that never stops breathing. If you’ve ever stood on a platform in July, sweat dripping down your back while waiting for a delayed G train, you’ve probably cursed its age. It feels ancient. It smells like history—and other things. But when people ask how old is the NY subway, they usually get a single, clean date: October 27, 1904.

That date is a bit of a lie. Well, not a lie, but it’s definitely not the whole story.

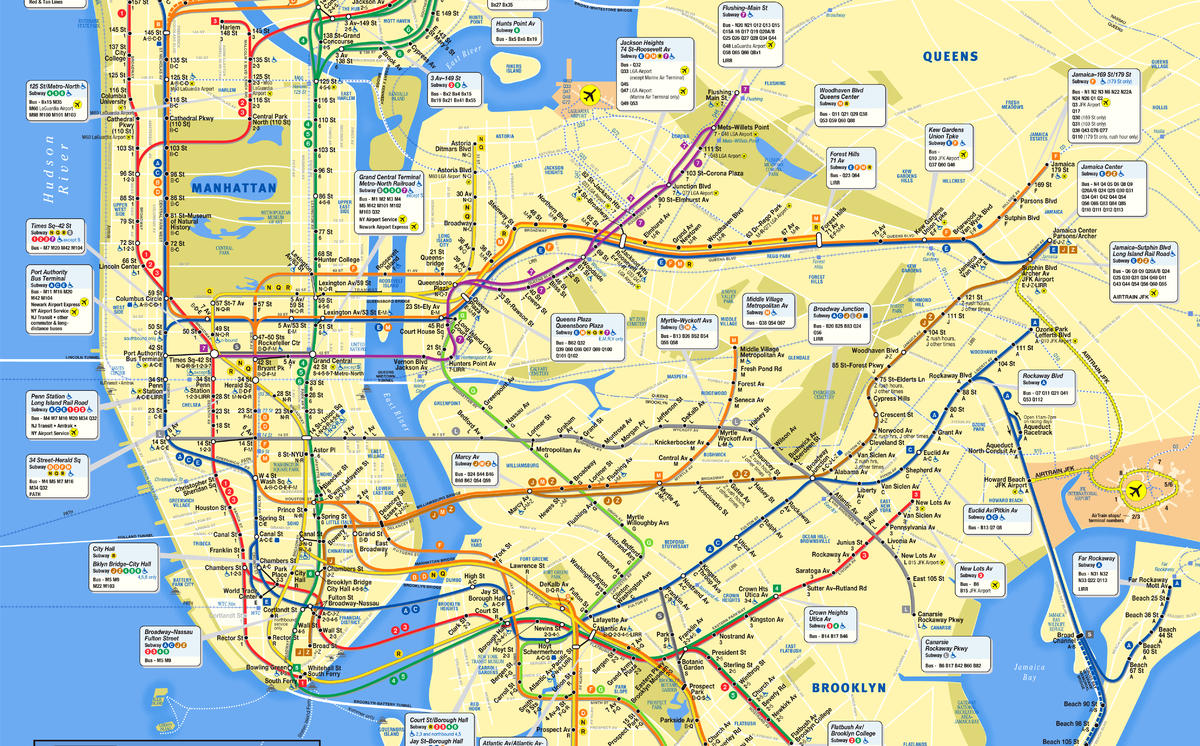

If you want to get technical, and New Yorkers love getting technical, parts of the system are way older than that. Other parts are basically brand new. It’s a Frankenstein’s monster of transit. You've got 19th-century elevated lines, early 20th-century deep tunnels, and the Second Avenue Subway which finally opened its first phase in 2017 after decades of being a punchline.

The 1904 "Official" Birthday

The Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) is the one that gets all the glory. At 2:35 PM on that Tuesday in October, Mayor George McClellan took the silver controller and drove the first official subway train from City Hall to 145th Street. It was a massive deal. People were terrified of going underground back then. They thought the air would be poisonous or the tunnels would collapse.

Honestly, the city was a mess before this.

Manhattan was becoming insanely crowded. Horse-drawn carriages were slow and, frankly, disgusting because of the sheer amount of manure left on the streets. The "L" trains—the elevated railroads—were already running, but they were loud, dirty, and sprayed soot on anyone walking underneath. The subway was supposed to be the clean, fast future.

The original line ran about 9 miles. It served 28 stations. If you look at a map today, that original route roughly follows the 4/5/6 lines from City Hall up to Grand Central, then cuts across the 42nd Street Shuttle to Times Square, and then heads north along the 1/2/3 lines to Harlem.

Why "how old is the NY subway" is a trick question

If we are talking about when New Yorkers first started riding trains on tracks to get around, 1904 is way too late.

Beach’s Pneumatic Transit is the weirdest piece of this puzzle. In 1870, a guy named Alfred Ely Beach built a secret tunnel under Broadway. He did it under the guise of a mail tube because the corrupt "Boss" Tweed wouldn’t give him a permit for a passenger rail. It was a single-block tunnel where a cylindrical car was literally blown back and forth by a giant fan. It was more of a carnival ride than a subway, but it was underground. It only lasted a few years before it was shut down, but it proved the concept.

📖 Related: Why San Luis Valley Colorado is the Weirdest, Most Beautiful Place You’ve Never Been

Then you have the "L" lines.

The Ninth Avenue El started operating in 1868. These weren't subways, but they were the foundation of the system. In the 1940s, the city started tearing these down and moving the service underground. So, while the tunnel might be from the 1930s, the route and the service history go back to the mid-1800s.

Even some of the actual subway tracks we use today predate 1904. The BMT lines in Brooklyn—specifically the West End and Sea Beach lines—started as surface steam railroads heading to Coney Island in the 1860s and 70s. Eventually, they were sunk into open cuts or put onto elevated structures and connected to the subway system.

When you ride the Q train through Brooklyn, you’re basically traveling on a path laid out right after the Civil War.

The Era of the Three Companies

For a long time, the "subway" wasn't one thing. It was three competing companies that hated each other.

- The IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit): These were the "First" ones. Their tunnels are narrower and their cars are shorter. This is why a 1 train can’t run on the same tracks as an A train today.

- The BMT (Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit): This came a bit later. They had wider cars and focused heavily on connecting Brooklyn to the business hubs.

- The IND (Independent Subway System): This was the city-owned disruptor. The Mayor at the time, John Hylan, hated the private companies. He wanted a "City-owned and City-operated" system. The IND lines (like the A, C, E, F, and G) are the ones with the massive, cavernous stations because they were built to compete with and eventually replace the other two.

The city finally bought everything in 1940 and merged them. That’s why the system is such a confusing maze. You have stations like Atlantic Avenue-Barclays Center or Fulton Street where you’re walking through a labyrinth of tunnels; you're literally walking between the old bones of three different companies that never intended to share a hallway.

Construction that defied the era

Building this thing was a nightmare. They used a method called "cut-and-cover."

They didn't have the massive tunnel-boring machines (TBMs) we have now. Instead, they literally dug up the street, laid the tracks, and built a roof over it. Imagine digging up Broadway today. It would be an absolute catastrophe. Back then, they just did it. They moved pipes, sewers, and gas lines by hand.

👉 See also: Why Palacio da Anunciada is Lisbon's Most Underrated Luxury Escape

Thousands of workers, mostly immigrants from Italy and Ireland, worked in brutal conditions. It was dangerous. In 1902, a massive dynamite explosion at Park Avenue killed several workers and shattered windows for blocks.

The depth of the stations tells you how old is the NY subway in that specific spot. Deep stations like 191st Street (the deepest in the system) were built using mining techniques through solid rock. Shallow stations like those on the Upper West Side were cut-and-cover.

The Mid-Life Crisis and the 1970s

By the time the subway hit 70 years old, it was falling apart. This is the era of the "Warriors" aesthetic. Graffiti covered every square inch. The tracks were "deferred maintenance" personified. Trains derailed constantly.

In 1981, the system was so bad that the MTA (formed in 1968) basically had to start over. They spent billions on the "New York Subway" as we know it today—replacing thousands of cars, fixing the tracks, and scrubbing the graffiti.

If you ask a historian how old the subway is, they might point to 1982 as its "rebirth." Without that massive infusion of cash, the 1904 system would have likely collapsed under its own weight.

Modern Additions: The Newest Old Subway

Is the subway 120+ years old? Yes. Is it 7 years old? Also yes.

The Second Avenue Subway (the Q extension) opened its first phase on January 1, 2017. Before that, the 7 train extension to 34th Street-Hudson Yards opened in 2015. These stations look like they belong in a different city. They have high ceilings, elevators that actually work, and no peeling lead paint.

But even these "new" parts are haunted by age. The Second Avenue line was first proposed in 1919. They started digging in the 70s, stopped because the city went broke, and let the tunnels sit empty for decades.

✨ Don't miss: Super 8 Fort Myers Florida: What to Honestly Expect Before You Book

Technical Evolution: From Signals to Screens

One of the biggest struggles with an aging system isn't the tunnels—it's the brains.

Most of the NYC subway still runs on "fixed block signaling." This technology is effectively from the early 1900s. It uses mechanical "trips" on the tracks to stop a train if it gets too close to another. It’s incredibly safe, but it's slow. You can’t run trains close together.

The MTA is slowly (painfully slowly) switching to CBTC (Communications-Based Train Control). The L train and the 7 train have it. This is why they generally run more frequently and feel "smoother."

Upgrading the rest of the system is like trying to install a fiber-optic network into a medieval castle without breaking the walls. It takes forever.

Why the age matters for your commute

The age of the system is the reason for the "Weekend Service Changes" we all hate.

Because the subway runs 24/7—one of the few in the world to do so—there is no "downtime" for maintenance. In London or Tokyo, they shut down at night and fix things. In New York, the only way to fix a 100-year-old pump or replace a rotting tie is to shut down a track on Saturday and Sunday.

When you see a "Track Work" poster, you’re seeing the price we pay for having a system that never sleeps.

Actionable Insights for Navigating the History

If you want to actually see the age of the system instead of just reading about it, there are a few things you should do:

- Visit the New York Transit Museum: It’s located in an authentic 1936 subway station in Downtown Brooklyn. You can walk through vintage cars from every era, including the wooden ones from the early 1900s.

- Look at the tiles: In older stations like 81st St-Museum of Natural History or Astor Place, the mosaics often tell you what was above ground when the station was built. The IRT stations have a specific "Beaux-Arts" style that you won't find on the newer IND lines.

- The "City Hall Loop" Trick: If you stay on the 6 train after the last stop (Brooklyn Bridge), the train loops through the abandoned City Hall station to head back uptown. It’s the "crown jewel" of 1904 architecture with vaulted ceilings and glass skylights. You can see it through the window if you stay on the train.

- Check the station signage: If a sign says "To IND Trains," you know you're in the 1930s-era part of the system. If it's cramped and has low ceilings, you're likely in the 1904 IRT section.

The New York subway is roughly 122 years old if you go by the 1904 opening, but its DNA spans over 150 years of urban planning, political corruption, and engineering genius. It’s a mess, it’s beautiful, and it’s the only reason a city of 8 million people can actually function.

To get the most out of your rides, use apps like Transit or MYmta, but keep an eye on the walls. The history is written in the grime and the mosaics. If you're interested in more than just the "when," look into the "how"—the engineering of the East River tunnels remains one of the most underrated feats in American history.