You probably found it in a junk drawer. Or maybe a relative handed you a dusty paper roll and said, "Keep these, they're silver." (They aren't silver, by the way). Most people see that iconic profile of a Native American and the bulky bison on the back and immediately think they’ve hit the jackpot. I’ve spent years looking at these things, and honestly, the answer to what is a buffalo nickel worth is usually a reality check, though sometimes it's a genuine thrill.

Most of them are worth about fifty cents. Maybe a buck.

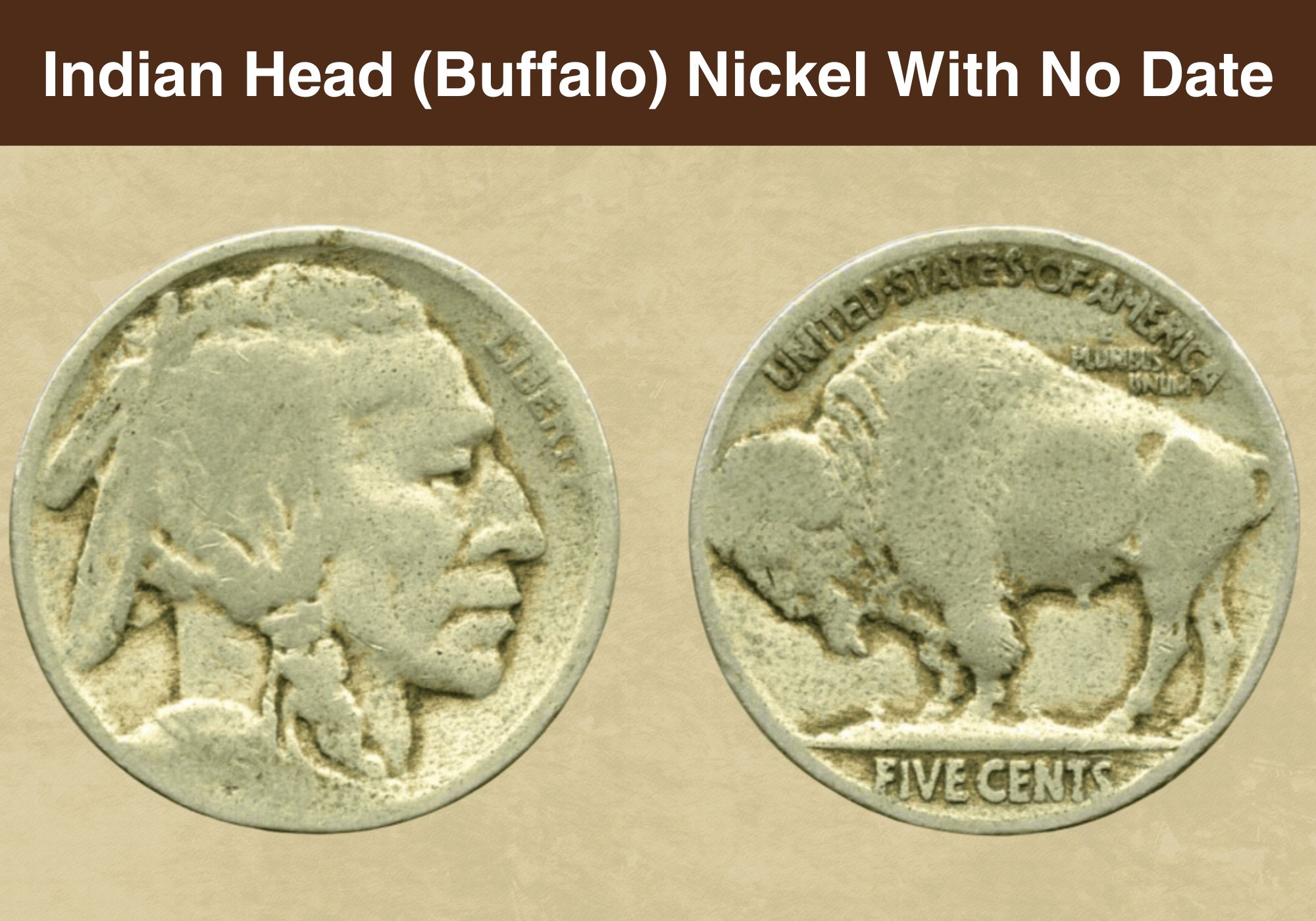

That’s the hard truth. But before you toss them back into the "someday" pile, you need to understand that the gap between a common 1936 nickel and a rare 1918/7-D overdate is the difference between a pack of gum and a down payment on a house. These coins, minted between 1913 and 1938, are notorious for one major design flaw: the date was positioned on a raised part of the design. It wore off fast. A Buffalo nickel without a date is basically worth its weight in copper-nickel alloy—which isn't much.

The Basics of Buffalo Nickel Valuation

So, what determines the price? Condition is king. If you can see the horn on the buffalo, you’re winning. If you can see the tail, even better. Professional numismatists use a 70-point scale, but for the average person, it’s about readability.

A common-date Buffalo nickel in "Good" condition (heavily worn but readable) typically sells for $1.00 to $2.00 to a dealer. If it’s a "dateless" coin, you’re looking at $0.10 to $0.25. However, the 1913 Type 1 is a different story. In 1913, the Mint changed the design because the "mound" the buffalo stood on caused the "Five Cents" text to wear away too quickly. They flattened the ground (Type 2). Because the Type 1 was only made for a few months, collectors still hunt for them.

Don't ignore the mint marks. Look at the reverse side, right under the words "Five Cents." If you see a 'D' (Denver) or an 'S' (San Francisco), you’re likely holding something more valuable than a plain coin from Philadelphia. San Francisco strikes are famously lower in mintage. For instance, a 1926-S is a monster of a coin. In high grades, it can fetch $50,000, but even in a well-worn state, it’s a $200 bill.

The Error Coins That Actually Matter

This is where things get weird and expensive. Collectors go crazy for mistakes.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

The most famous error is the 1937-D "Three-Legged Buffalo." It happened because a pressman at the Denver Mint got a bit too aggressive while cleaning a damaged die. He accidentally polished away the buffalo's front right leg. It’s hilarious, really. A mistake that should have been trash became one of the most sought-after coins in American history. If you have one, even in "Fine" condition, you’re looking at $500 to $800. In Mint State? $20,000+.

Then there’s the 1918/7-D overdate. This is when a 1918 coin was struck with a die that still had a 7 visible underneath the 8. It looks like a messy smudge to the naked eye, but under a loupe, it’s a goldmine. Finding one of these in a bulk lot is the dream of every coin hunter. It's rare. Really rare.

Grading: Why Your "Shiny" Coin Might Be Worthless

I see this all the time. Someone finds a nickel, notices it’s a bit dirty, and decides to scrub it with baking soda or silver polish.

Stop.

Cleaning a coin is the fastest way to destroy its value. Collectors want "original skin"—the natural patina and luster that forms over decades. A cleaned coin has a weird, unnatural "whited-out" look or microscopic scratches that tell a professional grader exactly what you did. A 1914-D that would have been worth $500 can drop to $100 the second you touch it with a cleaning cloth.

If you think you have a high-value coin, look for the "Full Horn." On the reverse, the buffalo’s horn is the highest point and the first thing to wear down. If that horn is sharp and complete, the coin is likely in "Extra Fine" or "About Uncirculated" condition. That’s when the price jumps from pocket change to serious money.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

Spotting the Key Dates

You don't need to memorize the whole catalog, but you should know the "Big Three" of the regular issues.

- 1913-S Type 2: This is the "Holy Grail" for many. With only about 1.2 million minted, it’s a scarce bird. Even a beat-up one starts around $300.

- 1921-S: Another low-mintage San Francisco beast. It’s tough to find with a decent strike. Most are "mushy." A sharp one is worth thousands.

- 1924-S: Often overlooked by beginners, but pros know it’s incredibly difficult to find in high grades.

Basically, if the date starts with 191 or 192 and has an 'S' on the back, pay attention. If it’s from the 1930s, it’s likely a "common" coin unless it has that missing leg or is in absolutely pristine, original condition with "rainbow toning."

The Chemical Secret: Nic-A-Date

What do you do with a nickel that has no date? There is a chemical called ferric chloride, sold as "Nic-A-Date." You drop a tiny bit on the date area, and it eats away the metal. Because the metal was compressed differently when the date was struck, the chemical reveals the numbers.

But there’s a catch.

A "restored date" coin is never worth as much as an original one. It leaves a permanent, ugly acid mark on the coin. Collectors call these "acid dates." They are fillers. A 1913-S Type 2 with an acid date might be worth $50 instead of $300. It’s a tool of last resort, mostly used by people trying to complete a "junk" set for fun.

Modern Market Trends in 2026

The market for Buffalo nickels has shifted lately. Younger collectors are less interested in "filling every hole" in a blue Whitman folder and more interested in "Eye Appeal." We’re seeing a massive premium for coins with beautiful, natural oxidation—purples, blues, and golds.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Also, the "Variety" market is exploding. Beyond the Three-Legged Buffalo, people are now hunting for the 1935 "Doubled Die Reverse." You’ll need a magnifying glass to see the doubling on the words "E Pluribus Unum" and "Five Cents," but if you find it, you’ve turned a nickel into $500.

Actionable Steps for Your Collection

If you’re sitting on a pile of these coins, don't just take them to a Coinstar. You’ll lose money and probably jam the machine. Here is how to actually handle them.

Sort your coins by date and mint mark first. If the date is missing, set it aside; it’s likely worth twenty cents to a "bulk" buyer. For the ones with dates, check the 1913-1926 range specifically. Use a 10x jeweler’s loupe to inspect the 1937-D for that missing leg. Look closely—if you see a "ghost" of a leg or a stump, it doesn't count. It has to be completely gone.

Check for "Lustre." Tilt the coin under a single light source. If the light "cartwheels" around the surface like spokes on a bike, the coin is uncirculated. These are the ones you should consider sending to a grading service like PCGS or NGC. It costs about $30-$50 per coin for grading, so only do this if the coin’s value is realistically over $150.

Finally, check the "rims." A strong, thick rim often indicates a better strike, which collectors prefer. If you decide to sell, avoid pawn shops. They usually offer "melt value" or a flat rate that ignores rarity. Instead, go to a dedicated coin shop or look at "Sold" listings on eBay to see what people are actually paying right now—not what they are asking.

The Buffalo nickel is a piece of American art. It’s messy, it’s imperfect, and it’s beautiful. Whether yours is worth a dollar or a thousand, it’s a tangible link to a very specific era of U.S. history. Just don't clean it. Seriously. Stay away from the soap.