Ever looked up at that tiny red dot in the night sky and wondered what it would actually cost to park a pair of boots there? It’s the ultimate "rich person" travel question, but honestly, the answer is a mess. You’ll hear some people talk about hundreds of billions of dollars like it’s pocket change, while others—mostly Elon Musk—claim we can eventually get there for the price of a nice house in California.

So, how much does it cost to go to mars? Right now, if you wanted to go today? You couldn't. Not for all the money on Earth. The tech isn't fully cooked. But if we look at the missions being built in 2026 and the cold, hard math of orbital mechanics, the price tag starts to come into focus. It’s a wild mix of government bureaucracy and billionaire bravado.

The Trillion-Dollar Question: Why Humans Are So Expensive

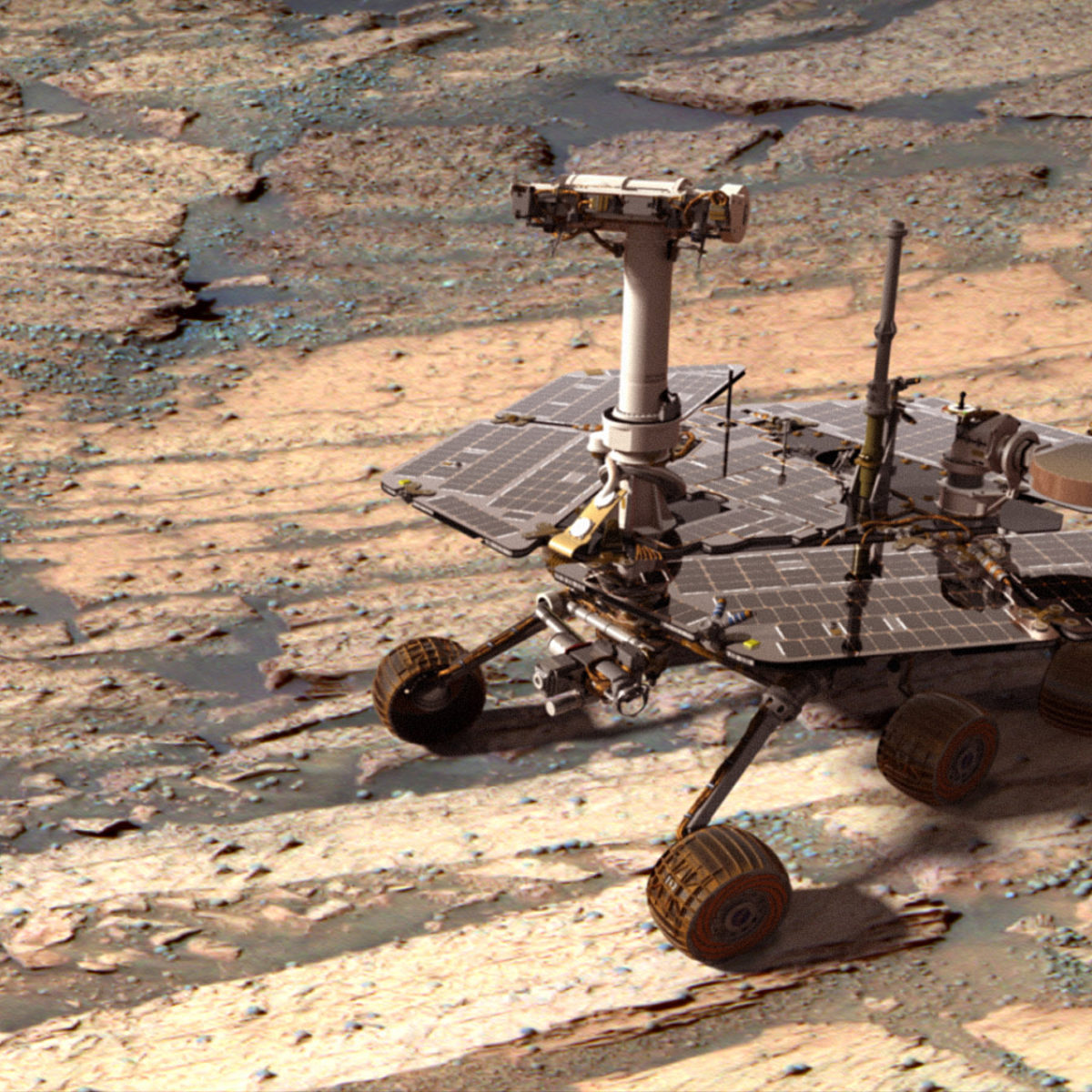

Let's be real for a second. Sending a robot to Mars is "cheap." NASA’s Perseverance rover, which is currently roaming the Jezero Crater, had a life-cycle price tag of about $2.7 billion. That sounds like a lot until you realize it’s basically the cost of one and a half B-2 stealth bombers.

📖 Related: Toronto Phone Book White Pages: What Most People Get Wrong

But humans? Humans are a nightmare to keep alive.

We need air. We need food that doesn't taste like cardboard for three years. We need protection from cosmic radiation that wants to shred our DNA. According to a 2024 report from the NASA Office of Inspector General and various studies from the International Conference on Environmental Systems, a single crewed mission to Mars could easily swing between $100 billion and $500 billion.

Think about that. That’s not just a "trip." That’s the cost of developing an entire planetary transport system from scratch.

Breaking Down the "Hidden" Costs

- Life Support: You’re looking at roughly $2 billion just to develop the systems that keep the air breathable and the water recycled.

- The Transit: It’s a six-to-nine-month commute. You need a habitat that won't leak or break down when you're 140 million miles from the nearest repair shop.

- The "Gas": Getting heavy stuff out of Earth's gravity well is the biggest budget killer.

SpaceX vs. NASA: Two Very Different Checkbooks

There is a massive rift in how we calculate these costs. NASA is currently focused on the Artemis program, using the Moon as a stepping stone. Their budget for 2026 is sitting around $24.4 billion, but a huge chunk of that is tied up in the SLS (Space Launch System) rocket, which costs about $2 billion per launch.

Then you have SpaceX.

Elon Musk is betting everything on Starship. His goal is to make Mars travel so routine that the cost of the rocket becomes almost irrelevant. SpaceX is currently aiming for a cargo rate of $100 million per metric ton to the Martian surface by 2030. If they can actually hit that, the economics change overnight.

Musk has famously stated he wants the ticket price to eventually drop to $100,000 to $500,000 per person. Is that realistic? Maybe in 2050. In 2026, it’s still very much a dream. But the fact that they are already testing orbital refilling—the "gas station in space" concept—shows they aren't just talking. If you can refuel in orbit, you don't need a rocket the size of a skyscraper to leave Earth. You just need a bunch of smaller, cheaper trips.

The Return Ticket Problem

Here is the thing nobody talks about: coming back.

It is exponentially cheaper to send someone on a one-way trip. To come home, you have to bring all the fuel for the return journey with you, or you have to build a chemical plant on Mars to manufacture it from the atmosphere. NASA’s Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission, which is just trying to bring back a few rocks, is already projected to cost over $11 billion.

Imagine trying to bring back four humans and their luggage.

This is why many experts, including those from the Aerospace Corporation, argue that the first missions won't be about "trips" at all. They will be about staying. If you don't have to launch a massive return vehicle off the Martian surface, you save tens of billions of dollars.

What You’re Actually Paying For

If we look at the 2026 federal budget requests, NASA is putting about $864 million into "Commercial Moon to Mars" infrastructure. This isn't for the rocket; it's for the boring stuff.

- High-speed comms relays ($80 million).

- Advanced space suits for the Martian dust ($50 million).

- Entry, Descent, and Landing (EDL) tech ($200 million).

These numbers show that we are still in the "buying the tools" phase, not the "booking the flight" phase.

✨ Don't miss: Apple Store in Penn Square: Why It Is Not Just Another Mall Shop

The Reality Check for 2026

So, if you wanted to be on that first ship, what’s the damage?

If the government does it, it’s a $200 billion project funded by taxpayers. If SpaceX manages to privatize it, you’re likely looking at an initial "founder's price" in the tens of millions of dollars—similar to what Axiom Space charges for a seat to the ISS ($55 million+).

The "cheap" Mars flight is a long way off. We are currently in the era of "Can we even do this without going bankrupt?"

To stay updated on how these costs are shifting, keep a close eye on the Starship flight tests in South Texas. Every time a Starship lands successfully and is ready to fly again, the "cost to go to Mars" drops a little bit more. The real breakthrough won't be a new engine; it will be the first time a rocket is reused so many times that the cost of the fuel is the most expensive part of the flight. Until then, Mars remains the most expensive destination in the known universe.

👉 See also: Why the Apple MacBook Pro M1 is Still the Best Value in 2026

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts:

- Track Starship's Reusability: Watch the turn-around time between SpaceX launches. Reusability is the only factor that will actually lower the price for individuals.

- Monitor NASA's MSR Budget: The Mars Sample Return mission is the "canary in the coal mine." If NASA can't figure out how to bring rocks back affordably, they won't be bringing humans back anytime soon.

- Invest in Education, Not Just Tickets: If you actually want to go, the best "cost-saving" measure is becoming an expert in ISRU (In-Situ Resource Utilization)—the tech used to make fuel and water on Mars. Those experts will be the ones getting their seats subsidized.