You’ve seen the magic number. 1,200 calories. It’s plastered across every fitness app and "thin-spiration" blog from the early 2010s like it’s some kind of universal law of physics. But here’s the thing: your body isn't a calculator. It’s a messy, adaptive, biological machine that doesn’t give a rip about what a generic website says you should eat.

Figuring out how much calories to take in to lose weight isn't about picking a random low number and suffering through it. If you go too low, your metabolism basically hits the panic button. If you go too high, well, the scale doesn't budge. It's a tightrope walk.

Let's get real for a second. Most people fail because they start with a deficit that is way too aggressive. They jump from eating 3,000 calories a day to 1,500 overnight. That’s a recipe for a binge-eating episode by Wednesday. To actually lose fat and keep it off, you have to find your "Goldilocks zone." This is the spot where you're eating enough to fuel your brain and workouts, but little enough that your body has to tap into its "savings account"—also known as body fat.

✨ Don't miss: Alcohol and Bulbous Nose: Why the "Gin Blossom" Myth is Still Hurting People

The Math Behind the Weight Loss Equation

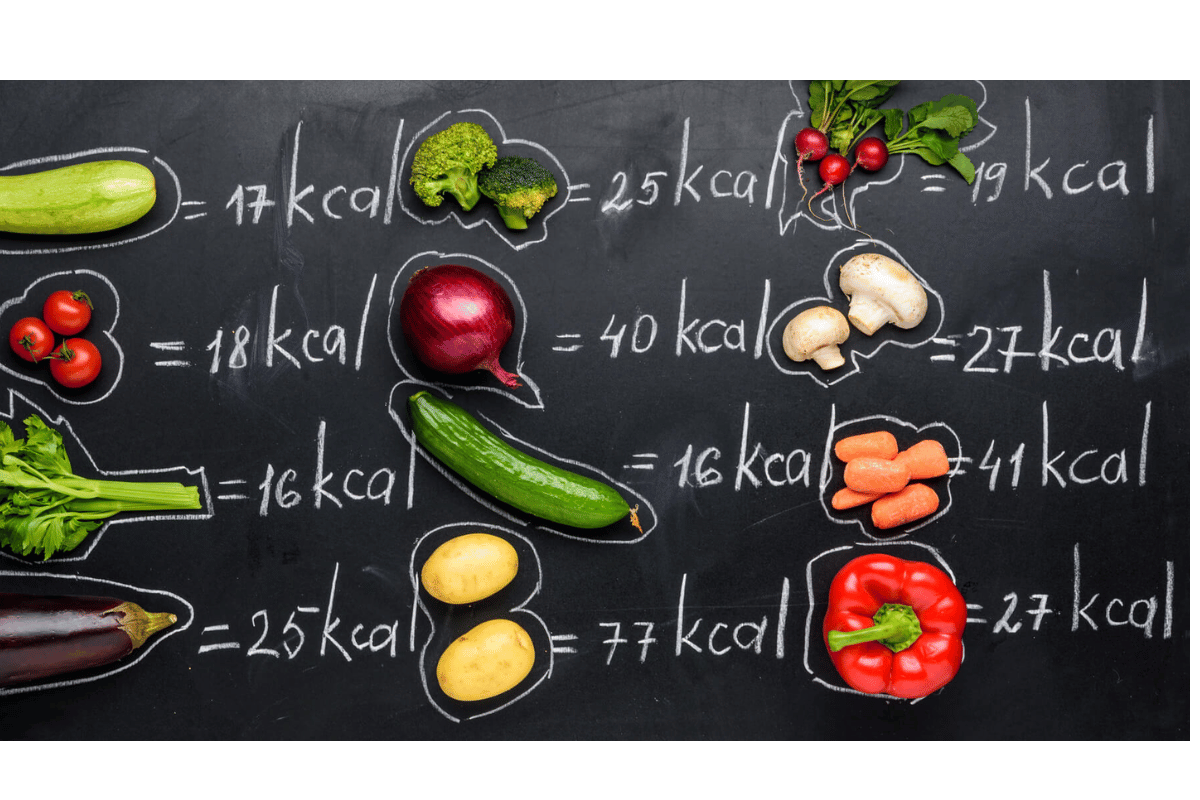

Calories are just units of energy. That’s it. To lose weight, you need a negative energy balance. You’ve probably heard of the 3,500-calorie rule. The old-school logic says that if you cut 500 calories a day, you’ll lose exactly one pound a week ($500 \times 7 = 3500$).

It’s a nice theory. Too bad it’s often wrong in practice.

Researchers like Kevin Hall at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have shown that as you lose weight, your body actually starts burning less energy. This is called adaptive thermogenesis. Your body thinks you're starving in a cave somewhere, so it gets "efficient." It lowers your heart rate, makes you fidget less, and slows down protein synthesis. So, that 500-calorie deficit might actually feel like a 200-calorie deficit after a month.

So, how do you actually start? You need to find your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). This is the sum of your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)—what you burn just staying alive—plus the energy you use for walking, working, and exercising.

If you're a 180-pound woman who sits at a desk all day, your TDEE might be around 2,000 calories. If you're a 220-pound guy who works construction, it could be 3,500. You see the gap? This is why generic advice is useless. You have to calculate your own starting point.

Why Your "Maintenance" is the Secret Weapon

Most people skip the most important step. They don't track what they're currently eating before they start a diet.

Honestly, before you try to figure out how much calories to take in to lose weight, you should spend seven days tracking your normal, everyday food intake. No judgment. No changes. Just data. If you eat 2,600 calories for a week and your weight stays the same, guess what? You found your maintenance.

Now, subtract 10% to 20% from that.

For someone eating 2,500 calories, a 20% cut is 500 calories. That puts you at 2,000. It’s a much more sustainable way to approach things than just guessing. It allows your hormones—like leptin and ghrelin—to stay somewhat stable so you don't feel like you're losing your mind every time you walk past a bakery.

✨ Don't miss: Gestational Diabetes Dinner Recipes: What Most People Get Wrong About Carbs

The Role of Protein in Your Calorie Budget

If you only focus on the total number of calories, you might lose weight, but you’ll probably look "skinny-fat." Why? Because without enough protein, your body will happily burn muscle for fuel alongside the fat.

Muscle is metabolically expensive. Your body wants to get rid of it if it’s not being used or fueled. Aiming for about 0.7 to 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight is a solid rule of thumb. If you're eating 1,800 calories, a huge chunk of that should be coming from chicken, tofu, eggs, or Greek yogurt. It keeps you full. It has a higher thermic effect of food (TEF), meaning you actually burn more calories just digesting protein than you do digesting fats or carbs.

Moving the Needle Without Starving

You can’t out-train a bad diet, but you can definitely use movement to give yourself more "room" in your calorie budget.

There's this thing called NEAT. Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis. It’s the energy you spend doing everything that isn't sleeping, eating, or intentional sports. Taking the stairs. Pacing while on a phone call. Folding laundry.

For many people, increasing NEAT is more effective for weight loss than hitting the treadmill for 30 minutes. If you burn an extra 300 calories a day just by being more active, you can eat an extra 300 calories of food and still be in the same deficit. That’s a whole extra snack or a much larger dinner.

Don't Fall for the "Starvation Mode" Myth (Mostly)

People talk about "starvation mode" like it’s a light switch that flips and stops all weight loss. That’s not quite how it works. You won't stop losing weight if you're truly in a deficit—look at the Minnesota Starvation Experiment if you want the grim proof.

However, "metabolic adaptation" is very real. If you've been dieting for six months and the scale has stopped moving despite eating very little, your body has adapted. You might be moving less without realizing it. You might be "mis-measuring" that tablespoon of peanut butter (which is actually 190 calories, not 90).

When this happens, the answer isn't always to eat less. Sometimes, the answer is a "diet break" where you eat at maintenance for a week or two to let your hormones recover.

Practical Steps to Find Your Number

Stop looking for a single number. Start looking for a range. Weight fluctuates daily based on water retention, salt intake, and even how much sleep you got last night. If you eat 1,800 calories one day and 2,000 the next, you haven't failed. You're just living.

- Calculate your BMR. Use a standard Mifflin-St Jeor formula online. It’s a guess, but a good one.

- Factor in activity. Be honest. If you work at a computer, you are "sedentary," even if you go to the gym for an hour.

- Set a conservative deficit. Start with 250-500 calories below your maintenance.

- Track for two weeks. Ignore the first three days (that's mostly water weight). Look at the trend from day 7 to day 14.

- Adjust based on reality. If you lost 0.5 to 1.5 pounds, stay there. If you lost nothing, drop another 100 calories. If you lost 5 pounds and feel like a zombie, eat more.

Listen, weight loss isn't a race. The faster you lose it, the more likely you are to lose muscle and the more likely you are to gain it all back. Focus on the highest amount of food you can eat while still seeing the scale trend downward. That is the true secret to long-term success.

Actionable Next Steps:

Download a tracking app like Cronometer or MacroFactor. For the next three days, don't change how you eat, but weigh everything you consume on a digital kitchen scale. Eyeballing "one cup" of pasta is almost always wrong—usually by 30% or more. Once you have a hard average of what you’re currently eating, reduce that total by 300 calories. Focus on hitting a protein goal of at least 100g per day to preserve muscle. Re-evaluate your progress in exactly 21 days; the trend line will tell you everything you need to know about whether your calorie target is working.