Everyone asks the same thing. You're staring at a nutrition label or scrolling through a fitness app, wondering how much calories should I consume to lose weight and actually keep it off this time. It’s frustrating. Most calculators give you a generic number that feels like it was pulled out of thin air. Honestly, the "2,000 calories a day" rule is basically a myth for anyone trying to get lean.

Weight loss isn't a math problem you solve once. It's a moving target.

If you eat too little, your thyroid slows down and your cortisol spikes. If you eat too much, well, the scale doesn't budge. You've probably heard of the 3,500-calorie rule—the idea that cutting that amount leads to one pound of fat loss. That’s old school. It’s based on research from Max Wishnofsky back in 1958. We know better now. Your body adapts. It fights back.

The math of maintenance vs. deficit

Before you can figure out your deficit, you need to know your TDEE. That's Total Daily Energy Expenditure. It’s the sum of everything you burn just by existing, plus your movement.

Most people overestimate how much they burn at the gym. A 30-minute jog might burn 300 calories, which is basically a large latte or a handful of almonds. To figure out how much calories should I consume to lose weight, you first have to find your baseline. If you've been maintaining your weight on 2,500 calories, dropping to 1,200 is a recipe for disaster. That’s a 50% cut. Your brain will literally start screaming at you to eat everything in the pantry by Tuesday night.

A "safe" deficit is usually around 15% to 25% below maintenance. For a woman who maintains at 2,000, that’s 1,500 to 1,700. For a guy at 2,800, it’s closer to 2,100. Small changes win. Huge changes fail.

Why your BMR isn't the whole story

Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) is what you burn if you stayed in bed all day in a coma. It’s the energy needed for your heart to beat and your lungs to breathe.

Never eat below your BMR.

✨ Don't miss: Fruits that are good to lose weight: What you’re actually missing

When you do that, your body enters a state called Adaptive Thermogenesis. This is what happened to the contestants on The Biggest Loser. Research published in the journal Obesity showed that years after the show, their metabolisms were still suppressed. They had to eat significantly less than a normal person of their size just to stay the same. You don't want that. You want a metabolism that works with you, not against you.

Protein is the non-negotiable variable

If you only track calories and ignore protein, you’ll lose weight, but you’ll look "skinny fat." You’ll lose muscle alongside fat. Muscle is metabolically expensive; it burns calories while you sleep.

Aim for roughly 0.7 to 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight. If you weigh 180 pounds, try to hit 130–150 grams of protein. It sounds like a lot. It is. But protein has the highest Thermic Effect of Food (TEF). About 20-30% of the calories in protein are burned just during digestion. Compare that to fats, where only 0-3% are burned.

Eating more protein literally makes your "calories out" number go up. It also keeps you full. Ghrelin, the hunger hormone, stays quiet when you're eating enough chicken, steak, tofu, or Greek yogurt.

The NEAT factor

NEAT stands for Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis. This is the "fidgeting" energy. It’s walking to the car, doing dishes, or pacing while on the phone.

When you cut calories, your body gets sneaky. It tries to save energy by making you move less. You might stop tapping your foot. You might sit down more often. This can account for a 200–500 calorie difference in your daily burn. This is why people "plateau" even when they think they are eating the right amount. They aren't lazy; their nervous system is just trying to conserve fuel.

How much calories should I consume to lose weight and stop plateauing?

Eventually, the weight loss stops. This is the part nobody likes to talk about. Your body is smaller now, so it requires less energy to move. If you started at 220 lbs and you're now 190 lbs, your 1,800-calorie diet might now be your maintenance diet.

🔗 Read more: Resistance Bands Workout: Why Your Gym Memberships Are Feeling Extra Expensive Lately

You have two choices here. You can drop calories further, or you can increase activity.

- Option A: Drop another 100 calories.

- Option B: Add a 20-minute daily walk.

- Option C: Take a "diet break."

Diet breaks are underrated. Spending two weeks eating at your new maintenance level can reset your hormones. It lowers cortisol. It lets your leptin—the fullness hormone—climb back up. Then, when you go back into a deficit, your body is more willing to let go of fat. It’s a marathon, not a sprint.

The role of fiber and volume

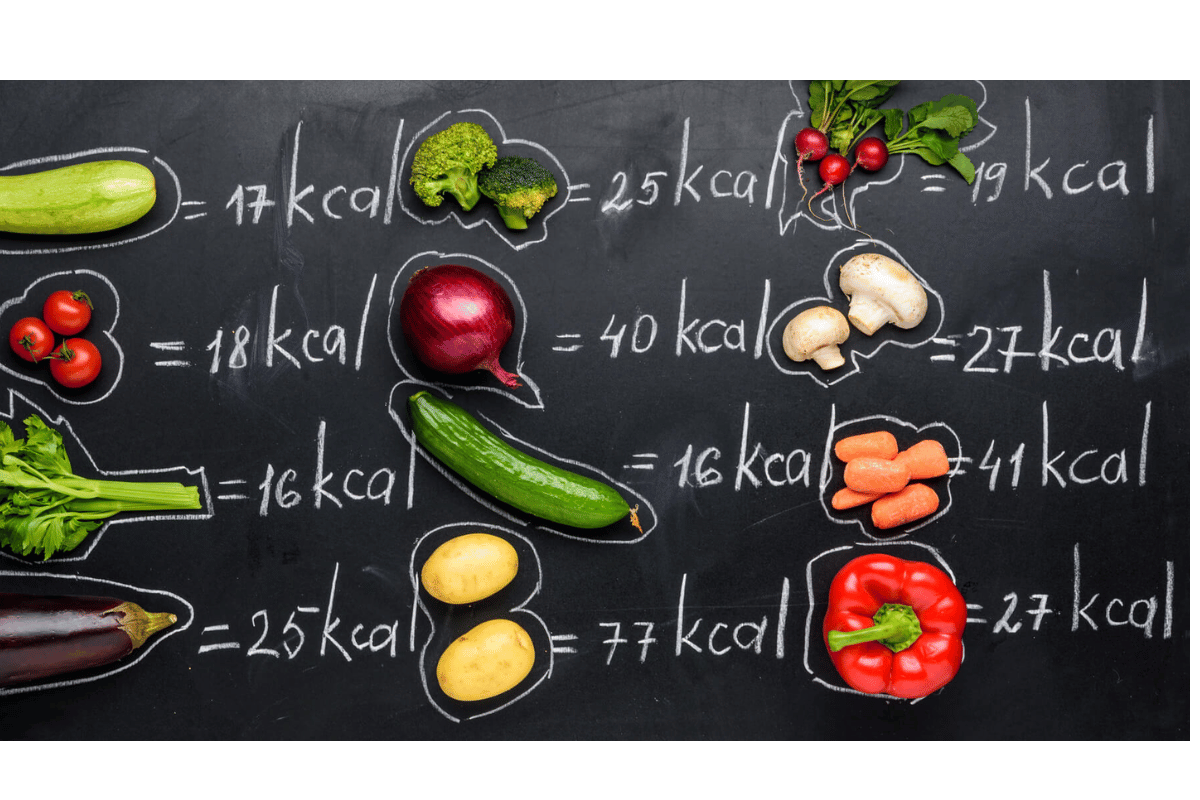

Fiber is your best friend when you’re cutting. Think about it. You could eat a tablespoon of peanut butter, or you could eat two cups of steamed broccoli. Both have the same calories.

Which one fills your stomach?

High-volume, low-calorie foods (like leafy greens, berries, and cucumbers) stretch the stomach lining. This sends signals to your brain that you're full. If you're constantly hungry, you're doing it wrong. You're probably eating calorie-dense processed foods that don't take up any physical space in your gut. Fill half your plate with vegetables. It's a cliché for a reason.

Tracking accuracy and the "weekend effect"

Most people are terrible at estimating calories. Studies show that even registered dietitians can underestimate their own intake by 10% to 20%. The average person? They might be off by 50%.

That "handful" of nuts is 200 calories. That "splash" of cream in your coffee is 60. That "bite" of your partner's dessert is 100.

💡 You might also like: Core Fitness Adjustable Dumbbell Weight Set: Why These Specific Weights Are Still Topping the Charts

Then there's the weekend. If you eat 1,500 calories Monday through Friday but hit 3,500 on Saturday and Sunday because "you earned it," your daily average for the week is actually 2,071. If your maintenance is 2,000, you are actually in a surplus. You will gain weight. You'll then wonder why your "1,500 calorie diet" isn't working. Consistency is the only thing the scale cares about.

Real-world expert steps to calculate your number

Stop using the generic calculators on the back of cereal boxes. Use the Mifflin-St Jeor equation. It's widely considered the most accurate for healthy adults.

For men: $10 \times \text{weight (kg)} + 6.25 \times \text{height (cm)} - 5 \times \text{age (y)} + 5$

For women: $10 \times \text{weight (kg)} + 6.25 \times \text{height (cm)} - 5 \times \text{age (y)} - 161$

Take that number and multiply it by an activity factor:

- Sedentary (office job, no exercise): 1.2

- Lightly active (1-3 days of exercise): 1.375

- Moderately active (3-5 days): 1.55

- Very active (6-7 days of hard exercise): 1.725

If your result is 2,400, subtract 500. That’s your starting point. 1,900 calories.

Track everything for two weeks. Watch the scale. If it moves down 0.5 to 2 pounds a week, you've found the sweet spot. If it doesn't move, your "activity factor" was probably too high. Lower the multiplier and try again.

Practical Next Steps

- Calculate your BMR using the Mifflin-St Jeor formula above to ensure you never eat below your physiological floor.

- Track your current "normal" eating for three days without changing anything to see what your true maintenance looks like.

- Set a protein goal of at least 0.7g per pound of body weight to protect your muscle mass during the deficit.

- Prioritize 8,000 steps a day to keep your NEAT high, which prevents your metabolism from slowing down as you eat less.

- Adjust every 4–6 weeks. As you lose weight, your calorie needs will decrease, and you'll need to slightly reduce intake or increase movement to keep seeing progress.