You’ve seen the images on the news a thousand times. Those iconic, rust-streaked blue or black drums sitting in a field or stacked on a tanker. Most people assume that when we talk about how much barrel oil costs or how much we’re producing, we’re talking about a container filled to the brim with gasoline.

It’s not. Not even close.

In reality, a "barrel" is a bit of a ghost. It’s a unit of measurement that hasn't physically existed as a standard shipping container for over a century. If you went to a refinery and asked to buy a physical barrel of crude, they’d probably look at you like you were lost. We use the 42-gallon standard because of some guys in Pennsylvania back in the 1860s who wanted to make sure they weren't getting ripped off during transport. They used old whiskey barrels. Why 42 gallons? Because a 40-gallon barrel often leaked or evaporated during the bumpy wagon ride to the river, so they added a "tax" of two extra gallons to ensure the buyer actually received 40.

That 160-year-old logistical headache is still how we measure the global economy today.

The Magic of Refinery Gain: Why 42 Becomes 45

Here is the first thing that trips people up. If you have a 42-gallon barrel of crude oil, you don't end up with 42 gallons of products. You actually end up with more.

Wait, what?

It’s called refinery gain. When you take heavy, dense crude and crack those complex hydrocarbons into lighter, less dense liquids like gasoline or butane, the volume expands. Think of it like making popcorn. You start with a small cup of kernels, and you end up with a massive bowl of fluffy corn. On average, a 42-gallon barrel yields about 45 gallons of refined products.

It’s basically the only time in physics where "more" comes from "less," at least in terms of liquid volume.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), that yield is a moving target. It depends entirely on the "API Gravity" of the oil. Light, sweet crude from the Permian Basin is going to give you a lot more gasoline than the thick, tar-like "heavy" oil coming out of the Canadian oil sands. Refining heavy oil is a grind. It requires more energy, more heat, and more chemical intervention to get it to behave.

💡 You might also like: Wegmans Meat Seafood Theft: Why Ribeyes and Lobster Are Disappearing

Breaking Down the Barrel: Where Does It All Go?

If you crack open that metaphorical barrel, you aren't just getting fuel for your Ford F-150. Crude oil is basically a chemistry set in a jar.

About 19 to 20 gallons of that barrel will become finished motor gasoline. That’s the big player. But the rest of the barrel is where things get weird. You get about 11 to 12 gallons of distillate fuel oil, which is most commonly sold as diesel or heating oil. Then you’ve got jet fuel, which takes up about 4 gallons.

The leftovers? That’s where the modern world lives.

We’re talking about "other products" like asphalt for roads, lubricants for your car's engine, and the feedstock for almost every plastic item in your house. Your toothbrush? Part of a barrel of oil. The polyester in your workout shirt? Oil. The medical-grade tubing in a hospital? Also oil.

Honestly, it's easier to list things that don't come from a barrel of oil.

The Gasoline Myth

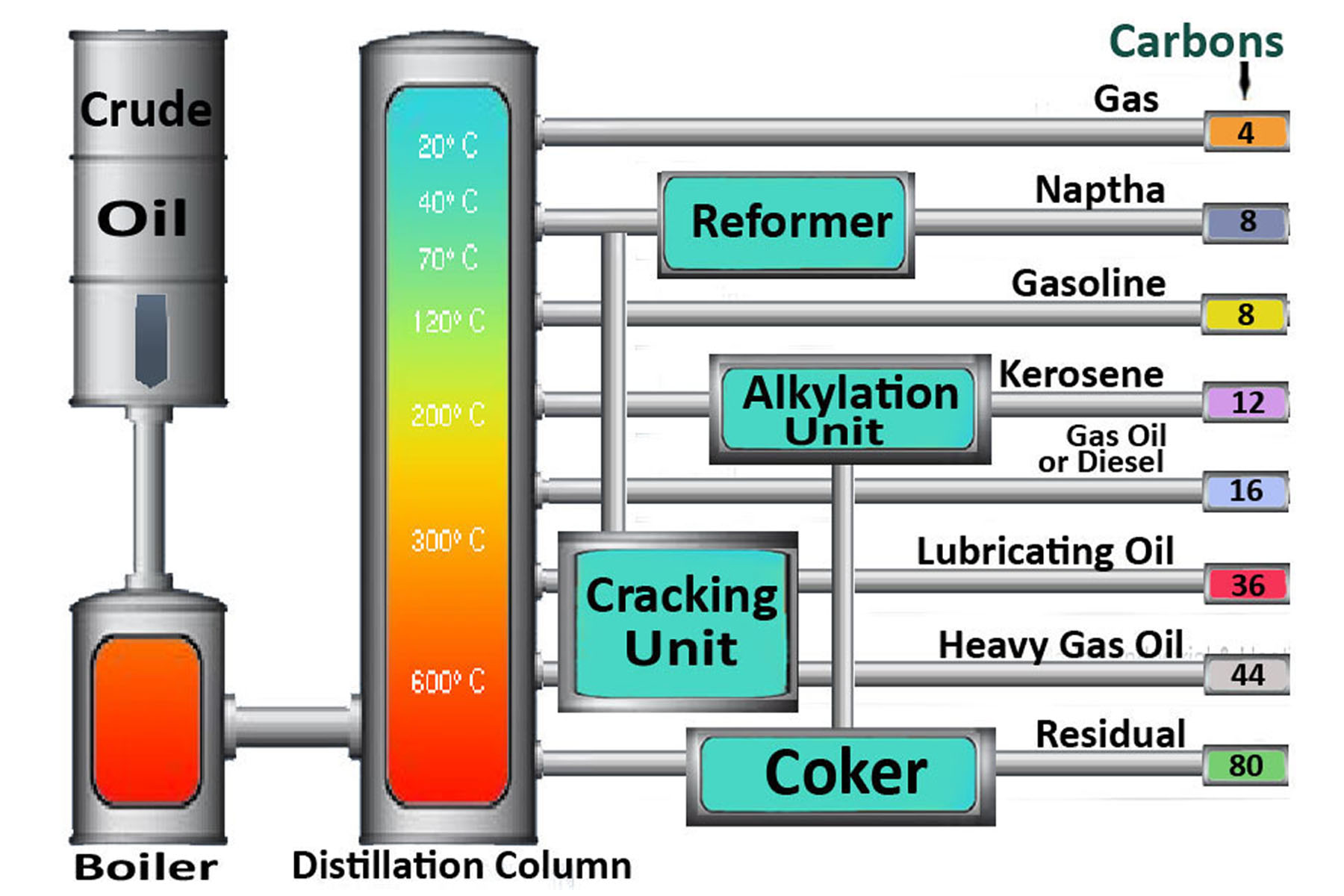

A common misconception is that refineries can just "choose" to make only gasoline if the price is high. They can't. A refinery is a giant distillation tower. You heat the oil, and the different components boil off at different temperatures. It's like baking a cake; you can't decide you want a cake made of 90% frosting after you've already mixed the batter. You’re limited by the chemical "cut" of the crude you started with.

Refiners use "crackers" and "coking units" to try and force more gasoline out of the heavier parts of the barrel, but there's a limit. This is why when diesel prices spike but gas prices stay flat, it’s often because the global shipping and trucking industry is starved for that specific middle-of-the-barrel cut, and the refineries simply can't squeeze out any more without making a bunch of gasoline they don't need.

The Economics of Scale: Global Consumption Patterns

When we ask how much barrel oil the world needs, the numbers become hard to wrap your head around.

📖 Related: Modern Office Furniture Design: What Most People Get Wrong About Productivity

In 2024 and heading into 2026, global demand has hovered around 102 to 104 million barrels per day.

Think about that.

Every single day, the world consumes enough oil to fill about 6,600 Olympic-sized swimming pools. If you lined up 100 million barrels end-to-end, the line would stretch roughly 56,000 miles. That’s twice around the circumference of the Earth. Every. Single. Day.

The U.S. remains the largest consumer, using about 20 million of those barrels daily. China is trailing but catching up fast as their petrochemical sector expands. Interestingly, the growth in "oil demand" isn't actually coming from cars anymore—electric vehicles (EVs) are starting to bite into that gasoline share. Instead, the growth is coming from petrochemicals. We are using more oil to make plastics, fertilizers, and synthetic materials than ever before.

Why "Sweet" and "Sour" Matter to Your Wallet

You might hear traders talk about "West Texas Intermediate" (WTI) or "Brent Crude." These aren't just fancy names; they describe the quality of the oil.

- Sweet oil has less than 0.5% sulfur. It’s easier to process.

- Sour oil is high in sulfur. It smells like rotten eggs and is corrosive to refinery equipment.

If a refinery is set up to handle sweet oil (like most in the U.S. Midwest), they can't suddenly switch to sour oil from Saudi Arabia without millions of dollars in upgrades. This creates "bottlenecks." Sometimes there's plenty of oil in the world, but it’s the "wrong kind" for the refineries that need it.

This is why you’ll see the price of a barrel of oil dropping on the news, but the price at your local gas station staying stubbornly high. The "crude-to-gasoline" spread—often called the crack spread—is the profit margin refineries make. If a refinery goes offline for maintenance, that spread widens. You pay more, even if the crude oil itself is cheap.

The Environmental Math

We can't talk about how much barrel oil we use without looking at the carbon cost.

👉 See also: US Stock Futures Now: Why the Market is Ignoring the Noise

Burning one barrel of oil produces roughly 430 kilograms of CO2.

That’s about 950 pounds of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere from a single 42-gallon drum. When you multiply that by 100 million barrels a day, you start to see the scale of the climate challenge. However, it's not just about the tailpipe. A significant portion of that carbon is "embedded" in products. When oil is turned into a plastic chair, that carbon is sequestered—at least until that chair ends up in an incinerator or breaks down in the ocean.

Surprising Uses You Probably Use Daily

Most people realize oil is in their car, but the reach of a single barrel is staggering.

- Aspirin: One of the precursors for salicylic acid often comes from petroleum byproducts.

- Solar Panels: Irony alert. The plastic films and resins used to hold solar cells together are made using oil.

- Makeup: Lipsticks and foundations often use paraffin wax or petrolatum.

- Food: Not directly, but the synthetic fertilizers (Haber-Bosch process) that grow about half the world's food supply rely heavily on natural gas and petroleum feedstocks.

What’s Changing in 2026?

We are currently in a weird transition period. Efficiency is skyrocketing. The average car today gets significantly better mileage than it did twenty years ago. At the same time, the "emerging middle class" in countries like India and Vietnam is buying their first scooters and cars.

We are approaching "Peak Oil Demand." Some experts, like those at the International Energy Agency (IEA), suggest we might hit it before 2030. Others, particularly in the OPEC+ camp, think that’s wishful thinking and that we’ll need these 100-million-barrel days for decades to come.

The reality is likely in the middle. We might stop burning as much oil for transport, but our "stuff"—our phones, our clothes, our medical equipment—will still be tied to that 42-gallon drum for the foreseeable future.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you want to track how oil impacts your personal economy, don't just look at the "Price of Oil" on the evening news. That's just the raw material.

- Watch the Crack Spread: If you see news about refinery outages in the Gulf Coast, expect gas prices to rise within 48 hours, regardless of what's happening with global crude prices.

- Check the API Gravity: If you’re investing in energy, know that "heavy" producers (like those in Canada) often trade at a discount to WTI because their oil is harder to cook.

- Audit Your Plastics: Look around your room. Almost everything that isn't wood, metal, or stone is a piece of a barrel of oil. Reducing plastic use is actually a more direct way to lower oil demand than many people realize, as the petrochemical sector is the fastest-growing part of the industry.

The "barrel" may be a 19th-century whiskey container, but it is still the pulse of the 21st-century world. Understanding that it’s a mix of gasoline, jet fuel, and the very fabric of our synthetic lives helps make sense of why a conflict halfway across the world or a refinery hiccup in Texas changes the price of your groceries.

Next time you see a 42-gallon drum, remember: it’s actually 45 gallons of "civilization" once the refinery gets through with it.

Key Data Summary

- Standard Barrel Size: 42 Gallons.

- Post-Refining Volume: ~45 Gallons (Refinery Gain).

- Typical Gasoline Yield: 19-20 Gallons.

- Typical Diesel Yield: 11-12 Gallons.

- Global Daily Consumption: ~102-104 Million Barrels.

- Carbon Footprint: ~430kg CO2 per barrel.

To stay informed on how these numbers shift, monitor the EIA Weekly Petroleum Status Report. It is the gold standard for seeing exactly how much oil is moving through the system in real-time. Paying attention to the "Distillate Stocks" section is often a better indicator of economic health than gasoline stocks, as diesel moves the trucks that move the economy.