Big numbers are weird. We use them all the time in news headlines about national debt or Elon Musk’s net worth, but honestly, most people can’t actually visualize the jump from a billion to a trillion. It sounds like they’re right next door to each other. They aren't. Not even close. If you’re trying to figure out how many zeros in a trillion versus a billion, you’re looking at a difference that is literally a thousand times larger.

Let's just get the raw data out of the way first. A billion has 9 zeros. A trillion has 12 zeros.

Writing it out looks like this:

1,000,000,000 (Billion)

1,000,000,000,000 (Trillion)

But just counting the circles at the end of the number doesn't tell the whole story. It’s the scale that messes with our heads. Humans are great at counting apples or sheep, but once we hit the "illions," our brains sorta just categorize everything as "a lot." It’s a cognitive bias that economists and mathematicians spend a lot of time worrying about because when we can't tell the difference between these scales, we make bad decisions about money and policy.

The Massive Gap: How Many Zeros in a Trillion Really Matters

When you add those three extra zeros to get to a trillion, you aren't just adding a little bit more. You are multiplying the billion by a thousand. That’s the part people miss.

Think about time. It’s the easiest way to feel the weight of these zeros. A million seconds is about 11 days. Not too bad. A billion seconds? That’s about 31 and a half years. Now, take a breath. A trillion seconds is roughly 31,700 years.

That is the difference between "the late 1990s" and "the era when woolly mammoths were still roaming the earth."

When we talk about how many zeros in a trillion, we’re talking about a scale that spans human civilization. If you spent a dollar every single second, it would take you 31 years to go broke if you had a billion dollars. If you had a trillion? You’d be spending for thirty thousand years. You would have outlasted the Roman Empire, the Egyptian Pyramids, and basically everything we call "history."

Why the Number of Zeros Changes Depending on Where You Live

Here’s a curveball: the answer to how many zeros in a trillion actually depends on your passport.

Most of the world uses what’s called the Short Scale. This is what you find in the United States, the UK (mostly, since the 1970s), and modern financial markets. In this system, every new "-illion" name represents a jump of 1,000.

- Million: $10^6$

- Billion: $10^9$

- Trillion: $10^{12}$

But if you go to France, Germany, or many countries in South America, they often use the Long Scale. In the long scale, a "billion" isn't a thousand millions; it’s a million millions. So, in those places, a billion has 12 zeros—the same as an American trillion. Their "trillion" (a million billions) has a staggering 18 zeros.

This causes massive confusion in international business. Imagine a diplomat from a Long Scale country talking about a "billion-dollar" trade deal with an American. They might be talking about two completely different realities. It’s one of those weird historical hangovers that still creates friction in global economics. The UK actually used the long scale until 1974, when Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey officially moved the country to the short scale to align with the US.

Visualizing the Zeros in the Real World

If you took a trillion $1 bills and stacked them on top of each other, how high would that go?

A stack of one billion $1 bills would reach about 67 miles into the sky. That’s already past the "edge of space" (the Karman line). But a trillion? That stack would reach 67,000 miles into space. That is more than a quarter of the way to the moon.

We see these numbers in the news constantly. The US national debt is currently hovering over $34 trillion. When you realize how many zeros in a trillion there actually are—and that we have 34 of them—the math starts to feel heavy. To pay off just one trillion of that debt by paying $1 million every single day, it would take you nearly 2,740 years.

The Scientific Notation Shortcut

At some point, the zeros become a nuisance. Imagine being an astrophysicist trying to calculate the number of stars in the observable universe. Typing out 24 zeros is a recipe for a typo.

This is why we use $10^{12}$ for a trillion. That little "12" is just a shorthand way of saying "put 12 zeros after the one."

In the world of data, we use prefixes.

- A billion bytes is a Gigabyte (GB).

- A trillion bytes is a Terabyte (TB).

Most of us have a terabyte hard drive in our laptops or gaming consoles. That means your computer is literally juggling trillions of tiny bits of information every time you boot it up. It’s pretty wild that we carry a "trillion" of anything in our backpacks, yet we still struggle to pay for a trillion-dollar infrastructure bill.

Does it stop at a trillion?

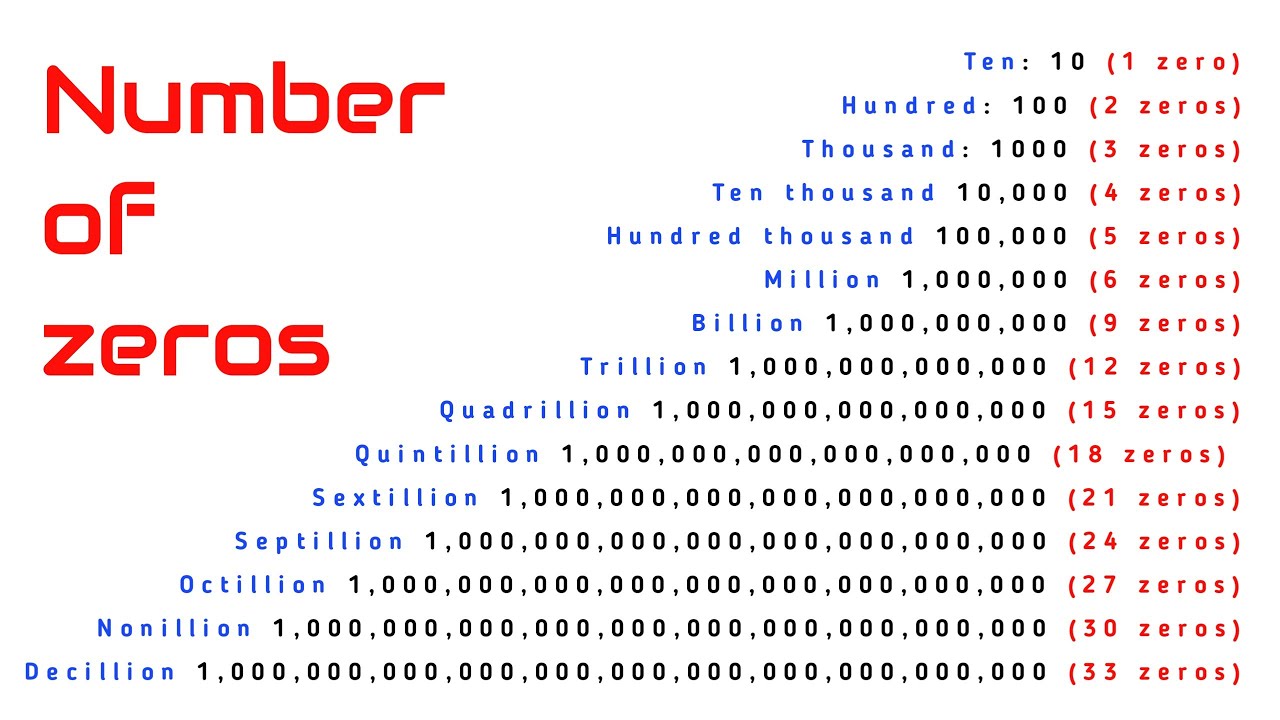

Hardly. Once you master how many zeros in a trillion, you run into the Quadrillion ($10^{15}$), the Quintillion ($10^{18}$), and the Sextillion ($10^{21}$).

If you want to get really crazy, look at the Avogadro constant used in chemistry. It’s $6.022 \times 10^{23}$. That’s the number of atoms in 12 grams of carbon-12. It’s a number so large that if you had that many unpopped popcorn kernels, you could cover the entire United Kingdom in a pile of corn 9 miles deep.

Why Our Brains Hate This

Evolutionarily, we didn't need to understand a trillion. Our ancestors needed to know if there were two lions or ten. They needed to know if the tribe had enough berries for twenty people. There was never a biological advantage to understanding the difference between a billion and a trillion.

This is what researchers call "Magnitude Neglect." We tend to treat all very large numbers as roughly the same "size" in our emotional centers. It’s why a charity might struggle to raise money if they say they need $10 billion versus $100 billion—to the average donor, both numbers just feel "impossible."

📖 Related: Why Gulf of America Still Matters for Global Trade and Energy

Actionable Steps for Navigating Big Numbers

Understanding the scale of zeros isn't just a party trick; it's a financial literacy skill. When you see these numbers in the wild, use these mental shortcuts to keep things in perspective:

- The Time Test: Always convert the number to seconds. If someone mentions a billion, think "31 years." If they say trillion, think "31,000 years." It immediately grounds the figure in a reality you can feel.

- The Per-Person Check: When you hear about a trillion-dollar government program, divide it by the population. In the US (roughly 330 million people), a $1 trillion expense is about $3,000 per person. That makes the "zeros" much easier to digest.

- Check the Scale: If you’re reading older British literature or documents from non-English speaking countries, double-check if they are using the Long Scale. A "billion" in an old UK text might actually be what we call a trillion today.

- Practice Scientific Notation: If you work in tech or finance, start thinking in powers of ten. It’s much harder to lose a zero when you’re looking at $10^9$ versus $10^{12}$.

The jump from 9 zeros to 12 zeros is the jump from a manageable (if massive) amount to a global, generational scale. Next time you see a trillion mentioned, remember the stack of bills reaching toward the moon. It’s the only way to keep the zeros from blurring together.