If you’re staring at a periodic table trying to figure out how many valence electrons are in f, you're likely hitting one of two very different walls. Maybe you're a chemistry student looking at Fluorine (F), the most reactive element on the board. Or, maybe you’ve tumbled down the rabbit hole of the "f-block"—those mysterious Lanthanides and Actinides sitting at the bottom of the chart like an abandoned basement.

Honestly, the answer depends entirely on which "f" you mean. Let's get the quick answer out of the way first. Fluorine has seven valence electrons. That’s it. But if you’re asking about the f-orbital or the f-block elements, things get weird. Fast.

The Straight Answer: Fluorine (F)

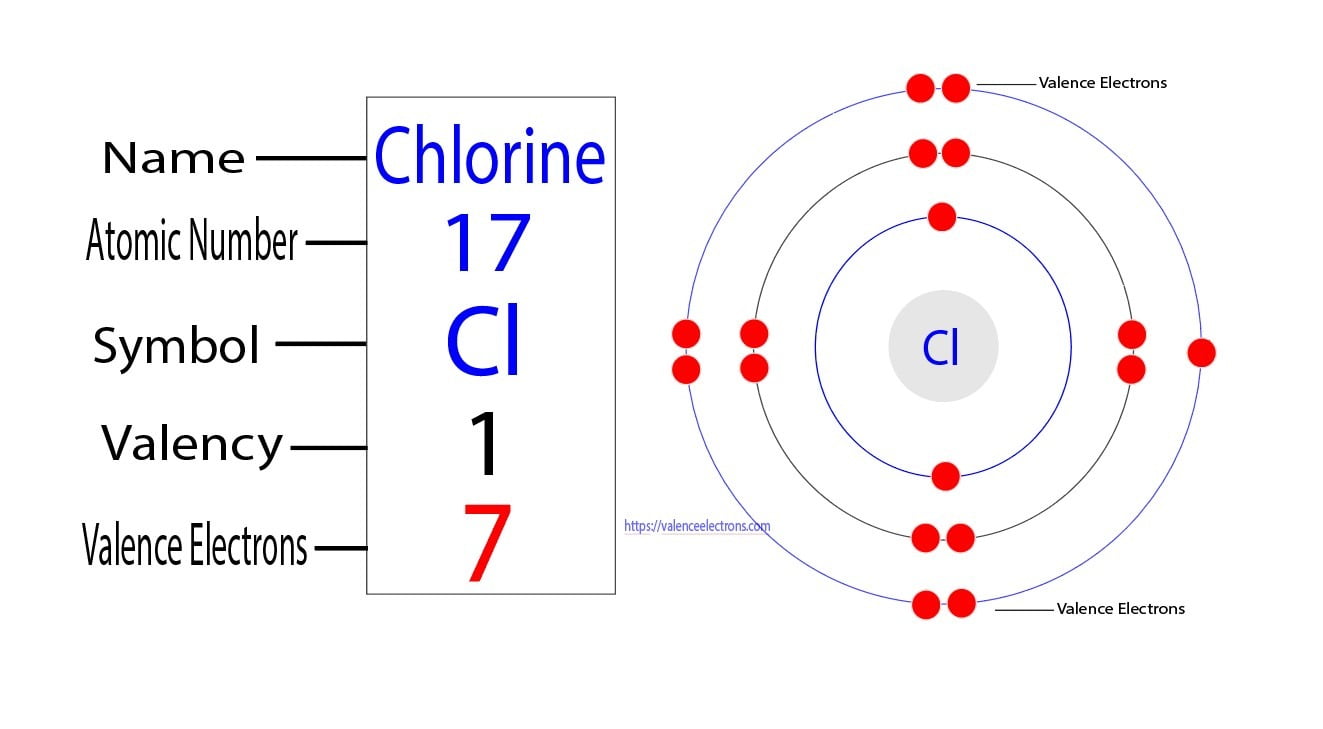

Fluorine is the poster child for the halogens. Located in Group 17, it has an atomic number of 9. If we look at its electron configuration, it looks like this:

$$1s^2 2s^2 2p^5$$

The valence electrons are the ones in the outermost shell. For Fluorine, that’s the second shell ($n=2$). Add up the two electrons in the $2s$ and the five in the $2p$, and you get seven. It is one electron away from a perfect octet. This is why Fluorine is basically the "honey badger" of the periodic table; it will tear electrons away from almost anything else to fill that gap.

But chemistry is rarely that simple once you move past the second row.

💡 You might also like: Starliner and Beyond: What Really Happens When Astronauts Get Trapped in Space

What About the F-Block Elements?

When people ask how many valence electrons are in f, they are often actually asking about the f-block. These are the elements where the $f$ subshell is being filled. We’re talking about elements like Neodymium, Uranium, or Plutonium.

Unlike the simple s and p blocks, the f-block doesn't follow the "group number equals valence electrons" rule. Not even close. In these heavy elements, the energy levels of the $s$, $d$, and $f$ orbitals are so tightly packed that they overlap.

Take Cerium ($Ce$), for example. Its configuration ends in $4f^1 5d^1 6s^2$. If you only count the outermost shell ($n=6$), it has two valence electrons. But in reality, those $4f$ and $5d$ electrons are often available for chemical bonding. Depending on who you ask—or more accurately, what kind of bond is being formed—Cerium might be considered to have three or even four valence electrons.

The Physics of Why F-Electrons are Different

Why is this so confusing? It’s because f-orbitals are "buried."

Imagine an onion. The $6s$ electrons are on the outer skin. The $4f$ electrons are a few layers deep. Usually, valence electrons are the ones on the skin, but because the $4f$ electrons are so high in energy, they can pop out and participate in reactions anyway.

📖 Related: 1 light year in days: Why our cosmic yardstick is so weirdly massive

Linus Pauling, a giant in the field of chemical bonding, spent ages trying to define electronegativity and bonding patterns for these heavier elements. Even today, researchers at places like Los Alamos National Laboratory are still debating the exact "valency" of certain actinides. It's not just academic fluff. If you're trying to store nuclear waste or design a new high-strength magnet, knowing exactly how those f-block electrons behave is the difference between success and a very expensive disaster.

The Periodic Table Lies to You (Slightly)

We often teach the "octet rule" like it's a law of nature. It’s more of a suggestion.

For the f-block, we sometimes talk about the 14-electron rule or even higher coordination numbers. Because there are seven distinct f-orbitals, and each can hold two electrons, you have a capacity of 14. When you combine that with the $d$ and $s$ orbitals nearby, you get atoms that can suddenly bond with twelve different neighbors at once.

If you are looking for a specific number for an f-block element, the most common answer is 2. Most of these elements have a $(ns)^2$ outer shell. However, their "valence" (the number of bonds they can actually form) is often 3.

Common Misconceptions About F-Electrons

- "The f-block doesn't matter." Wrong. Your smartphone vibrates because of f-block elements (Neodymium magnets).

- "Valence always means the outermost shell." In transition and inner-transition metals, this definition breaks. We usually include the $d$ or $f$ electrons that are energetically accessible.

- "Fluorine has f-orbitals." It doesn't. Fluorine is too small. Its electrons only fill the $1s, 2s,$ and $2p$ levels.

How to Calculate it Yourself

If you’re stuck on a homework problem or a research paper, follow this messy but reliable logic:

👉 See also: MP4 to MOV: Why Your Mac Still Craves This Format Change

- Identify the element. If it's Fluorine (F), the answer is 7.

- Check the period. If it’s in the lanthanide or actinide series, look at the Group 3 column.

- Use the Noble Gas shorthand. Write the configuration. For Europium ($Eu$), it's $[Xe] 4f^7 6s^2$.

- The "Safety" Answer. Usually, the two electrons in the highest $s$ orbital are the primary valence electrons. But if the question is about "available" electrons, you add the $f$ count.

Why This Matters for Modern Tech

We are currently in a "rare earth" arms race. Elements like Dysprosium and Terbium are essential for green energy. Their unique properties come specifically from those f-electrons. Because the f-orbitals are so shielded, they allow these atoms to maintain a magnetic moment even when packed into a solid.

If you're interested in materials science, the "valence" of the f-block is your bread and butter. It's what allows for the complex crystal field splitting that gives us lasers and fiber-optic amplifiers.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Electron Counts

To get this right every time, stop relying on the "shape" of the periodic table and start using energy diagrams.

- Download a high-resolution periodic table that specifically lists electron configurations. Don't guess.

- Practice the Aufbau Principle, but learn the exceptions. Chromium and Copper are the famous ones, but the f-block is full of them (like Gadolinium).

- Understand the "inert pair effect." As you go lower on the table, those outer s-electrons sometimes get "lazy" and don't want to bond, which changes the effective valence.

- Focus on oxidation states. For f-block elements, it's often more helpful to ask "What are the common oxidation states?" (usually +3) rather than "How many valence electrons are there?"

Whether you're dealing with the ferocity of Fluorine or the complexity of the Lanthanides, the "f" question is a gateway into the deeper, more chaotic reality of quantum chemistry. The rules you learned in 9th grade were just the beginning.