You’d think the number of people running the country would be a simple math problem. But if you’re looking for how many total house seats there are in the U.S. Congress, the answer is a weird mix of a hard cap, some non-voting observers, and a whole lot of 1920s drama.

Most people just say 435. They aren't wrong, exactly. But they aren't totally right either.

The Magic Number: 435

Basically, there are 435 voting members in the U.S. House of Representatives. This is the number that matters for passing laws, electing the Speaker of the House, and deciding who wins the presidency if the Electoral College ties.

It hasn't always been this way.

Back when George Washington was around, the House started with just 65 members. The Constitution basically said, "Hey, let's have one rep for every 30,000 people." As the country grew, Congress just kept adding seats. It was like a growing dinner party where you just keep dragging more chairs to the table. By 1911, the table was getting pretty crowded with 433 seats. Then Arizona and New Mexico joined the party, and we hit 435.

Then, things got weird.

After the 1920 census, Congress looked at the data and realized that the population was shifting from farms to cities. If they added more seats to keep everyone happy, the House would become "unmanageably large." If they didn't add seats, rural states would lose power to the cities.

📖 Related: Mark Milley Political Affiliation: What Most People Get Wrong

So, they did what politicians do best: they did nothing for a decade. They literally didn't reapportion the seats for ten years. Finally, the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929 fixed the number at 435.

The People Who Can’t Vote (But Are Still There)

While the "435" figure is the one you see on the news, the actual number of people sitting in the chamber is higher. There are 6 non-voting members who represent territories and the District of Columbia.

- District of Columbia: One delegate.

- Puerto Rico: One Resident Commissioner (who actually serves a four-year term instead of two).

- American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands: One delegate each.

These folks can do almost everything a regular representative can do. They can sit on committees, they can speak on the floor, and they can introduce bills. They just can't cast the final vote on the House floor that makes a bill a law.

So, if you’re counting warm bodies with office space on Capitol Hill, the total is 441. But for the purposes of "how many total house seats" determine the balance of power? It’s 435.

🔗 Read more: List of Australian Prime Ministers: What Most People Get Wrong

Why 435 is Kind of a Problem in 2026

Back in 1929, 435 seats meant each representative had about 210,000 constituents. Fast forward to today, and the average representative is looking at over 760,000 people.

That's a massive jump.

It makes it harder for you to get a meeting with your rep. It makes it easier for special interests to drown out individual voices. And, honestly, it makes the Electoral College a bit of a mess because those 435 seats (plus the 100 Senators and 3 DC electors) are what determine who becomes President.

There's a lot of talk lately about the Wyoming Rule. The idea is simple: take the population of the smallest state (Wyoming) and make that the unit for one seat. Then divide the rest of the country by that number. If we did that, the House would probably swell to over 500 or even 600 seats.

The Reapportionment Shuffle

Every ten years, we do the Census. After that, those 435 seats get shuffled around like a deck of cards. This is called reapportionment.

If your state grew like crazy (looking at you, Texas and Florida), you gain seats. If your state stayed flat or shrank (sorry, New York and Illinois), you might lose one.

Even though the total number of house seats stays at 435, the distribution changes. This triggers redistricting, where state legislatures or commissions have to redraw the lines. This is where the "G-word" comes in: Gerrymandering. When the lines are drawn specifically to help one party win, it changes the entire flavor of the House without ever changing the total seat count.

💡 You might also like: Preparing for a Trump Presidency: What Most People Get Wrong

What Happens if a Seat Goes Vacant?

You might check the news today and see that the "total" isn't 435. That's usually because of deaths, resignations, or someone getting a promotion to a Cabinet position.

In the Senate, governors can often just appoint a replacement. In the House? No way. The Constitution requires a special election.

Until that election happens, the seat is just... empty. The total possible seats is 435, but the active number of voting members might be 432 or 434 for months at a time. This can actually be a huge deal when the majority is thin. If a party only has a two-seat lead and three of their members resign, they effectively lose control of the floor until those special elections are finished.

Actionable Insights for the 2026 Cycle

Understanding the seat count isn't just trivia; it's how you track power. As we head into the 2026 midterms, keep these realities in mind:

- Watch the Vacancies: A 435-seat House is only "full" on paper. Check the current partisan breakdown to see how many seats are actually active.

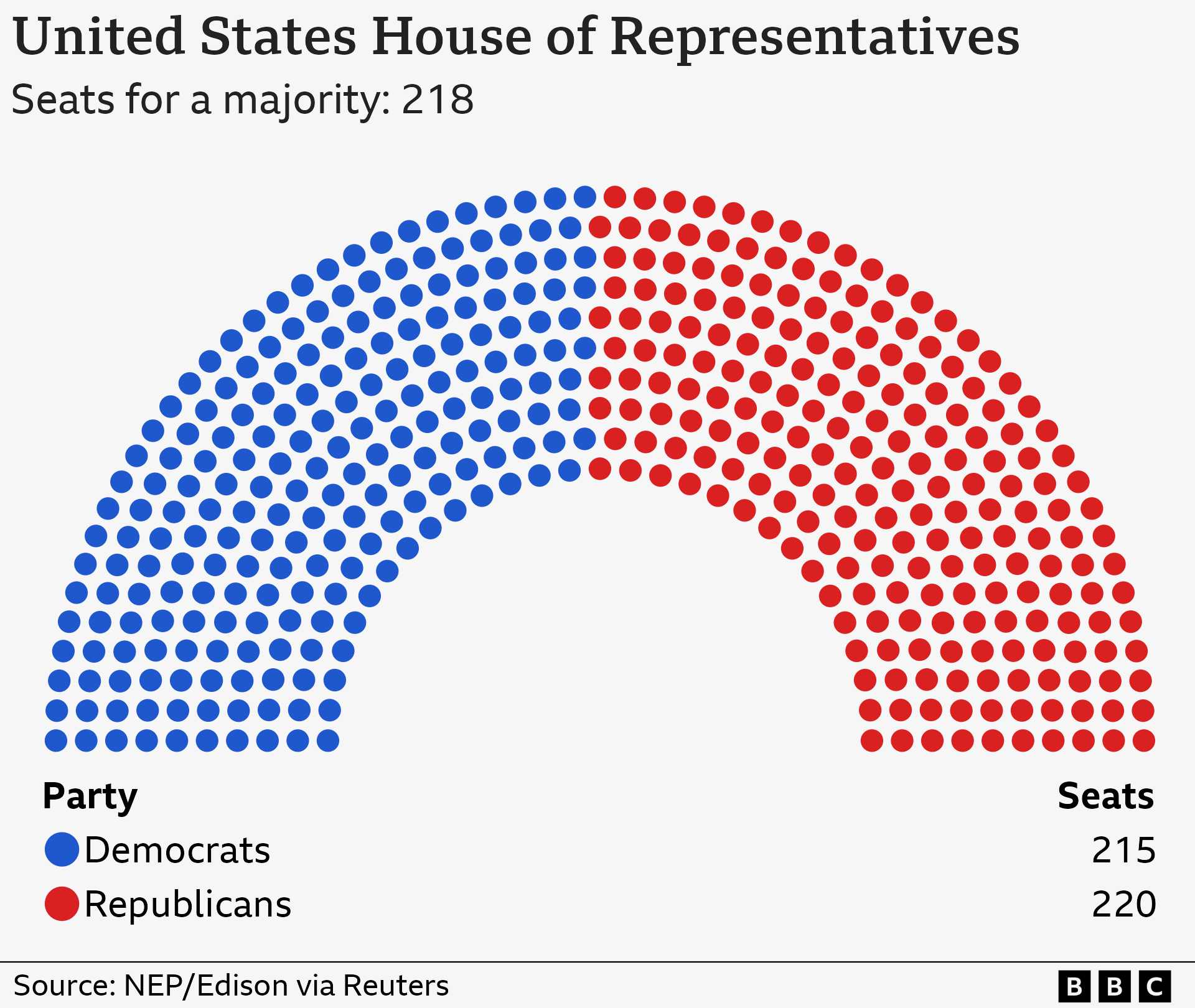

- The 218 Threshold: To pass anything, you need a simple majority. In a full House, that's 218. If vacancies exist, that number effectively stays the target, but the "math" of who shows up to vote becomes much more tense.

- Follow the State-Level Changes: Even though the total hasn't changed since the last Census, the 2026 elections are the third cycle using the current maps. Look at states that barely gained or lost seats; those districts are often the most competitive "swing" areas.

- Engage with the "Expand the House" Debate: There are active movements and even bills in Congress looking to repeal the 1929 Act. Knowing that the 435 limit is just a law—not a Constitutional requirement—is the first step in understanding how the "how many total house seats" question might have a different answer in the next decade.

The number 435 is a historical accident that became a permanent fixture. Whether it stays that way depends on whether the 119th Congress or future sessions decide that the dinner table finally needs a few more chairs.