You probably haven’t thought about the trillions of viruses currently living on your skin, in your gut, or swimming in your coffee. It’s okay. Most people don’t. But if we’re talking about how many species of bacteriophages actually exist, we’re venturing into a territory where math starts to feel like science fiction.

Bacteriophages—or just "phages"—are viruses that eat bacteria. They are the most abundant biological entities on Earth. Period. If you took every grain of sand on every beach and multiplied it by a billion, you still wouldn’t even be close to the number of phages on this planet. Scientists generally estimate there are $10^{31}$ individual phage particles globally. That’s a one followed by thirty-one zeros. It’s a number so large it makes the national debt look like pocket change.

But individuals aren't species.

The Magnitude of Phage Diversity

Trying to pin down exactly how many species of bacteriophages exist is like trying to count the drops of water in a hurricane while you’re standing in the middle of it. For a long time, we were limited by what we could grow in a petri dish. If we couldn't grow the host bacteria, we couldn't see the phage. This led to a massive "dark matter" problem in biology. We knew things were there, but we couldn't name them.

Then came metagenomics. Basically, scientists started scooping up dirt, seawater, and sewage, then sequencing every bit of DNA they found. The results were humbling. A single gram of soil can contain thousands of different phage genotypes. Most of these have never been seen before. They don't have names. They don't have "species" designations in the traditional sense.

In the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) database, the number of officially recognized species is surprisingly low—only a few thousand. But that’s just the paperwork catching up to reality. It's a tiny, microscopic fraction of the true diversity. Estimates for the actual number of viral "clusters" or species-like groups range from hundreds of thousands to tens of millions. Honestly? We might never have a final number.

👉 See also: Why the Ginger and Lemon Shot Actually Works (And Why It Might Not)

Why the "Species" Concept Breaks Down

Biology loves boxes. We like to say "this is a lion" and "that is a tiger." But viruses don't play by our rules. Bacteriophages engage in horizontal gene transfer so often that their genomes are like mosaics. They swap parts. They steal bits of DNA from their hosts. They evolve so fast that by the time you've sequenced one, its "species" might have diverged into something else.

Dr. Graham Hatfull from the University of Pittsburgh has spent decades running a program called SEA-PHAGES. They get students to isolate phages from their own backyards. What they found is wild: almost every time a student finds a new phage, it's unique. Even if they find two phages that infect the same bacteria (like Mycobacterium smegmatis), the genetic difference between them can be massive.

The Scale of Discovery

- Oceanic Phages: In the world's oceans, phages kill about 40% of all bacteria every single day. This drives global nutrient cycles.

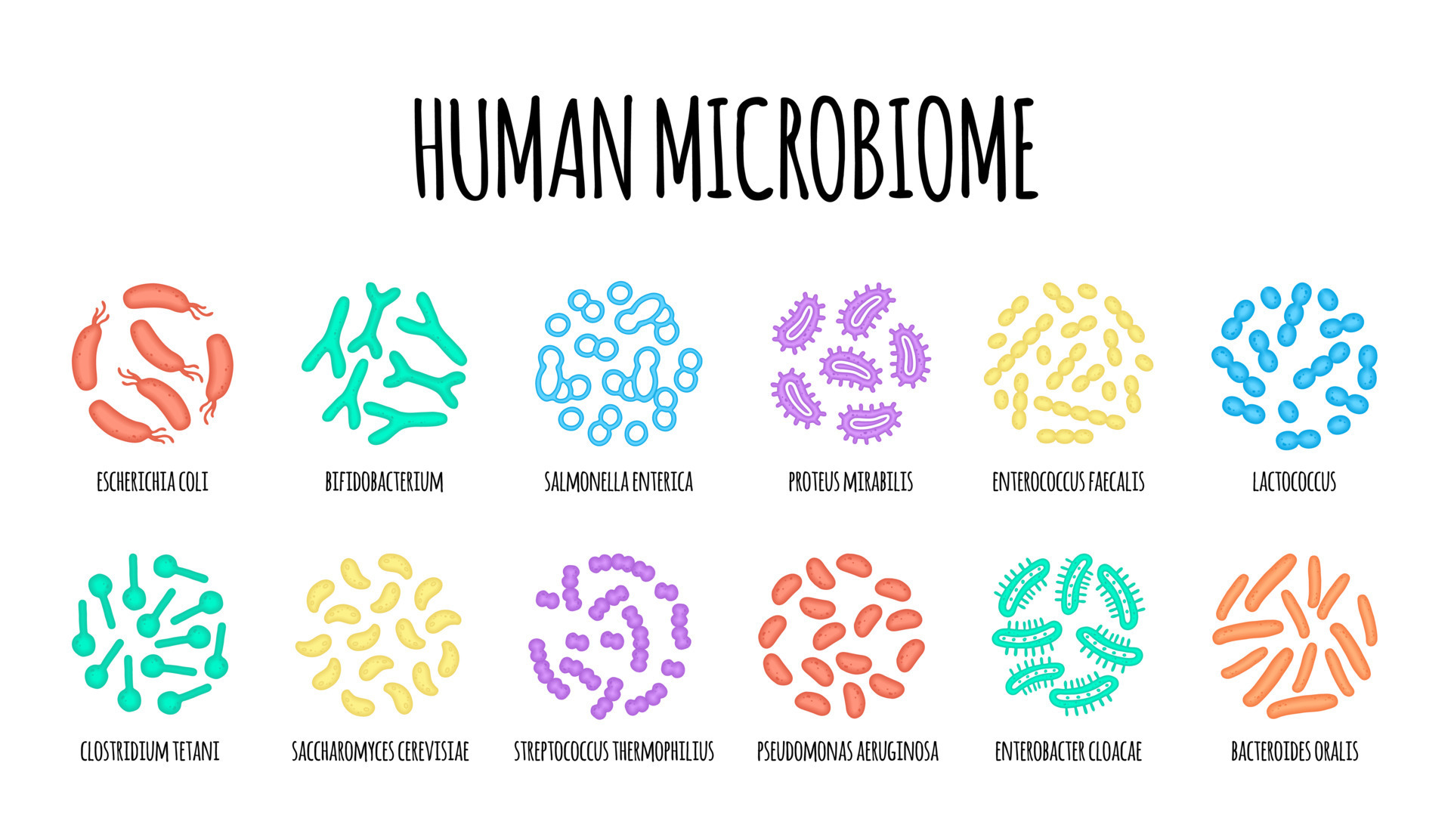

- The Human Virome: You have a personal "virome." Most of the viruses in your body are phages that keep your microbiome in check.

- Specialization: Most phages are highly specific. A phage that kills E. coli usually won't touch Salmonella. This specificity is why they are so promising for medicine.

Phage Therapy and the Antibiotic Crisis

The reason people are suddenly obsessed with how many species of bacteriophages there are isn't just curiosity. It’s survival. We are running out of working antibiotics. Superbugs like MRSA and Acinetobacter baumannii are winning.

Phages are the natural enemy of these bacteria. Because there are so many species, there is almost certainly a phage out there that can kill any specific antibiotic-resistant strain. We just have to find it. This isn't theoretical. In 2016, Tom Patterson, a professor at UC San Diego, was dying from a multi-drug resistant infection. His wife, Dr. Steffanie Strathdee, worked with researchers to find specific phages in sewage and barnyards that could kill his specific infection. It worked. He woke up from a coma and survived.

This "boutique" medicine relies on the sheer diversity of phages. If there were only a few hundred species, we’d be in trouble. But because there are millions, the "library" of potential cures is nearly infinite.

✨ Don't miss: How to Eat Chia Seeds Water: What Most People Get Wrong

What Most People Get Wrong About Phages

You’ll hear people say phages are "alive." That’s a hot debate in biology. They don't have a metabolism. They don't breathe. They’re basically genetic instructions wrapped in a protein coat. They’re "biological hackers."

Another misconception is that they are dangerous to humans. They aren't. Your immune system sees them, sure, but a bacteriophage cannot infect a human cell. Their "keys" only fit bacterial "locks." You could drink a cocktail of a billion phages right now and you'd be fine—well, your gut bacteria might have a rough afternoon, but you wouldn't get a viral infection.

The Future of Phage Taxonomy

So, where do we go from here? The ICTV is moving away from just looking at what a phage looks like under a microscope (its morphology) and moving toward genome-based taxonomy. This is the only way to handle the flood of data.

We are entering the era of "dark viral matter." Projects like the Earth Virome Initiative are trying to map this landscape. But every time we look, the horizon moves further away. We find phages in extreme environments: hot springs, deep-sea vents, and Antarctic ice.

The diversity is the point.

🔗 Read more: Why the 45 degree angle bench is the missing link for your upper chest

The evolutionary pressure phages put on bacteria is what keeps life on Earth balanced. Without phages, bacteria would overgrow, consume all nutrients, and the ecosystem would collapse. They are the unseen regulators of the biosphere.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you're interested in the world of phages, you don't need a PhD to get involved or stay informed. Here is how you can actually engage with this science:

Track the Research: Keep an eye on the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH) at UC San Diego. They are the leaders in bringing phage therapy to the mainstream.

Contribute to Science: Programs like SEA-PHAGES often have citizen science components. If you're a student or an educator, you can actually help discover and name new species. Imagine having a virus named after you because you found it in a scoop of dirt behind a Starbucks.

Support Phage Banking: One of the biggest hurdles in medicine is the lack of a "phage library." Organizations are working to create standardized banks of sequenced phages so doctors can find a match for an infection in hours, not weeks. Supporting initiatives that fund these "bio-banks" is crucial for the post-antibiotic era.

Understand the Limits: While phages are amazing, they aren't a magic bullet yet. The FDA still struggles with how to regulate a "living" drug that evolves. Realizing that phage therapy is currently an "experimental" or "compassionate use" treatment helps manage expectations for families dealing with resistant infections.

The sheer volume of how many species of bacteriophages exist is our greatest backup plan. Nature has already built the world's most sophisticated pharmacy. We just need to finish cataloging the shelves.