Hurricanes are terrifying. There is no other way to put it when you see a wall of water taller than your house rushing toward the front door. You’ve probably seen the news footage of palm trees snapping like toothpicks and reporters leaning into 100 mph winds, but the question that always lingers after the satellite feed cuts out is a grim one: How many people die from hurricanes every year?

The answer isn't as straightforward as a single digit on a chart. It’s a messy, heartbreaking mix of direct impacts—like drowning in a storm surge—and the quiet, lonely deaths that happen weeks later when the power is still out and the heat becomes unbearable.

Historically, we used to think of hurricane deaths as a "wind" problem. We were wrong. It turns out, wind is rarely the killer. According to data from the National Hurricane Center (NHC), roughly 90% of direct fatalities in tropical cyclones are caused by water. Specifically, storm surge accounts for about half of those deaths.

If you look at the last few decades, the average number of deaths per year in the United States fluctuates wildly. Some years it's under a dozen. Other years, like 2005 or 2017, the numbers climb into the thousands. It makes you realize how much we rely on infrastructure that can fail in a heartbeat.

Why the Official Death Toll Often Lies

Counting the dead is surprisingly political and scientifically difficult. When Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017, the initial "official" death toll was 64. People knew that wasn't right. It felt wrong.

How could a Category 4 storm destroy an entire island's power grid and only kill 64 people? Researchers from Harvard University eventually stepped in. They looked at "excess mortality"—the difference between how many people died during the storm period versus a normal year. Their estimate? Nearly 3,000 people.

This happens because of indirect deaths. If a grandfather’s nebulizer stops working because the electricity is out, and he passes away, does that count as a hurricane death? Most experts say yes. The CDC has tried to standardize this, but local coroners often have different rules.

- Direct Deaths: Drowning, being hit by falling trees, or buildings collapsing.

- Indirect Deaths: Heart attacks from shoveling sandbags, carbon monoxide poisoning from poorly placed generators, or infections from contaminated floodwaters.

Honestly, the generator issue is a massive, preventable tragedy. Every time a major storm hits the Gulf Coast, we see a spike in carbon monoxide deaths because people run generators in their garages to keep the AC on. It’s a silent killer that has nothing to do with the wind speed.

The Shift from Wind to Water

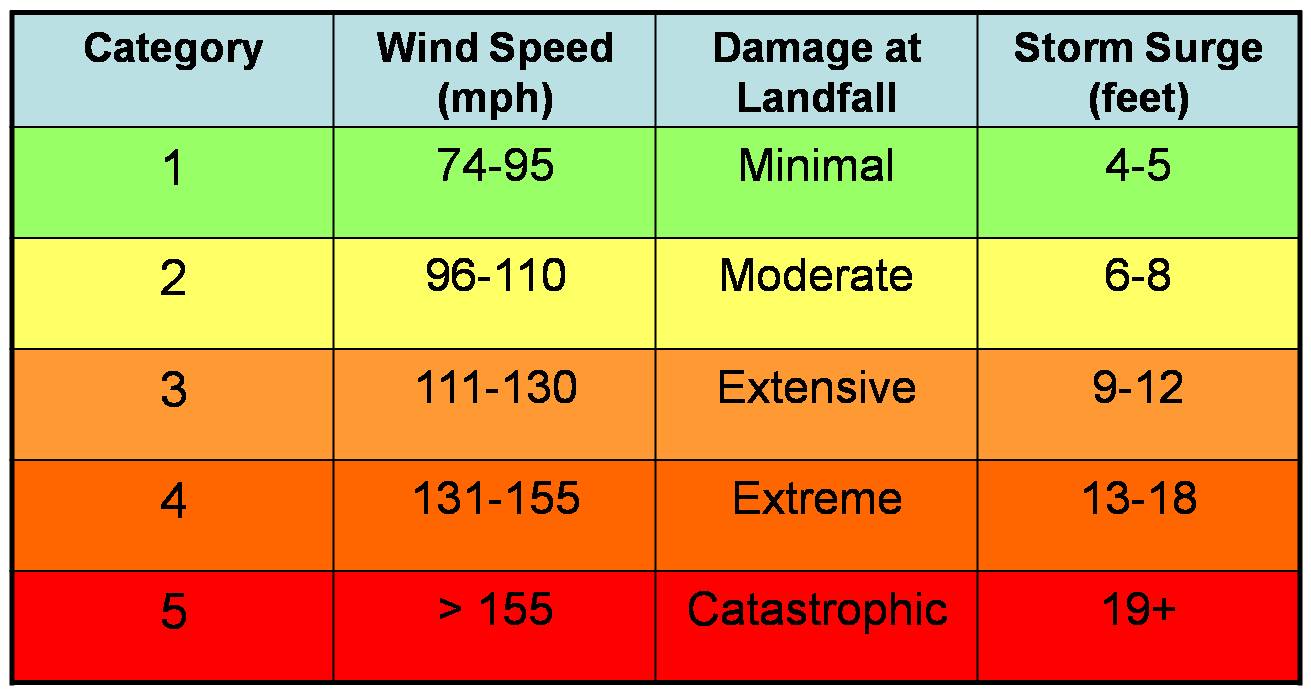

We spend so much time talking about Category 3 vs. Category 5. The Saffir-Simpson scale is based entirely on wind. But if you want to know how many people die from hurricanes, you have to look at the rain.

Take Hurricane Harvey in 2017. It wasn't the wind that crippled Houston; it was the fact that the storm parked itself over the city and dumped 50 inches of rain. People drowned in their living rooms.

📖 Related: NIES: What Most People Get Wrong About the National Institute for Environmental Studies

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has been screaming this from the rooftops for years: "Turn around, don't drown." It sounds like a cheesy catchphrase until you see a minivan swept away in six inches of moving water.

Edward Rappaport, a former deputy director of the NHC, conducted a landmark study on hurricane fatalities from 1963 to 2012. His findings were sobering. Freshwater flooding from torrential rain caused 27% of deaths, while storm surge caused 49%. High winds? Only about 8%.

Vulnerable Populations and the Inequality of Survival

Wealth plays a bigger role in survival than most people want to admit. If you have a car, a credit card, and a hotel reservation inland, your chances of being a statistic go down drastically.

But what if you rely on public transit? What if you can't afford a tank of gas?

During Hurricane Katrina, we saw the intersection of poverty and geography. The people who died were disproportionately elderly, poor, and Black. Many were trapped in nursing homes or stayed because they had no way to leave. It’s a recurring theme. Even in 2022, with Hurricane Ian, we saw many elderly residents in Fort Myers Beach perish because they simply couldn't—or wouldn't—evacuate their homes in time.

The Long Tail of Recovery

The danger doesn't end when the sun comes out. In fact, the weeks following a storm can be just as lethal as the storm itself.

Think about the heat. After a major hurricane, the humidity is stifling and the power is often out for weeks. For the elderly or those with chronic health conditions, this is a death sentence. Heat exhaustion and heat stroke are massive contributors to the "indirect" death counts we talked about earlier.

Then there's the "chainsaw effect." Every year, people who survived the storm unscathed end up in the ER—or the morgue—because they tried to clear a fallen oak tree without knowing how to properly handle a chainsaw. Or they fall off a ladder while trying to patch a roof.

It’s these mundane accidents that pad the numbers of how many people die from hurricanes. It’s not always a cinematic disaster; sometimes it’s just a slip on a wet tile floor in a dark house.

👉 See also: Middle East Ceasefire: What Everyone Is Actually Getting Wrong

Global Perspective: When Numbers Skyrocket

While the U.S. might see dozens or hundreds of deaths, other parts of the world face unthinkable catastrophes. In 1970, the Bhola cyclone hit East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The death toll is estimated at 300,000 to 500,000 people.

Why was it so high?

- Extremely low-lying geography.

- High population density.

- Lack of an advanced early warning system.

When we talk about hurricane deaths in a modern, Western context, we are lucky. We have satellites. We have iPhones that scream at us when a surge is coming. In many parts of the world, a "hurricane" (or cyclone/typhoon) is still an unpredictable monster that wipes out entire villages without a moment's notice.

Misconceptions That Get People Killed

There’s this weird bravado people get. "I stayed for the last one, and I'll stay for this one."

This is dangerous for two reasons. First, every storm is different. A Category 2 with a massive wind field can push more water into your house than a compact Category 4. Second, your house might have been weakened by the last storm.

Another big mistake is the "Eye" of the storm. When the wind stops and the sky clears, people head outside to check the damage. They don't realize the backside of the eyewall is coming, often with even more ferocity. They get caught in the open.

And then there's the "it's just a tropical storm" fallacy.

Tropical Storm Allison (2001) never even became a hurricane. Yet, it caused dozens of deaths and billions in damage because it just wouldn't stop raining. Labels matter for insurance, but they don't matter to the water.

What the Data Tells Us About the Future

Are hurricanes getting deadlier? That’s a complicated "sorta."

✨ Don't miss: Michael Collins of Ireland: What Most People Get Wrong

We are getting better at forecasting. The "cone of uncertainty" is getting narrower every year thanks to better modeling and more data points from "hurricane hunter" aircraft. Because we can predict where a storm will land with more accuracy, we can evacuate people more effectively.

However, more people are moving to the coast. The census data shows an explosion of growth in Florida, Texas, and the Carolinas. More people in harm's way means the potential for a mass-casualty event is always increasing, even if our technology gets better.

Also, sea levels are rising. This means the storm surge starts from a higher baseline. A surge that would have stayed in the street thirty years ago is now entering the first floor of homes.

Practical Steps to Avoid Becoming a Statistic

Knowing how many people die from hurricanes should be a wake-up call, not just a trivia point. Survival is often a matter of preparation and humility.

First, know your zone. Don't guess if you're in an evacuation area. Check your local government's flood maps. If they tell you to go, go. They aren't trying to ruin your weekend; they are trying to keep first responders from having to risk their lives to pull you off a roof.

Second, get a NOAA Weather Radio. Your phone is great, but cell towers fail. A battery-operated or hand-crank radio will give you life-saving info when the grid goes dark.

Third, respect the water. If you see water over a road, you have no idea if the pavement underneath has been washed away. It takes very little force to move a vehicle. Just stay put or find a different route.

Fourth, plan for the "after." Have a way to stay cool. Have a two-week supply of any life-saving medications. If you use a generator, keep it at least 20 feet from the house. No exceptions.

Finally, check on your neighbors. The elderly man living alone next door might not have a smartphone or a car. A five-minute conversation could literally be the difference between him surviving the storm or becoming one of those tragic "indirect" statistics.

The reality of hurricane fatalities is that most are preventable. We can't stop the wind and we can't hold back the ocean, but we can get out of the way. The numbers tell a story of human vulnerability, but they also show us where we need to be smarter. Don't let a lack of planning make you part of the count.

Take a look at your local evacuation routes today. Map out two different ways to get at least 50 miles inland. Pack a "go-bag" with your essential documents, a flashlight, and extra batteries. Doing this during a sunny afternoon is a lot easier than trying to do it while the wind is howling and the power is flickering. Survival isn't about being brave; it's about being ready.