You're standing in the kitchen, staring at a yogurt container, and doing mental gymnastics. We've all been there. You want to know how many calories to lose a day to lose weight, but the "advice" out there is a mess. Some fitness influencer says you need to starve. A calculator tells you to eat 1,200 calories. Your friend says they lost 20 pounds just by skipping bread. Honestly, most of it is noise.

Weight loss isn't a magic trick. It's biology, but biology is messy.

The standard answer you’ll find in old textbooks is that you need a 500-calorie deficit every day to lose one pound a week. This is based on the 3,500-calorie rule. The idea is simple: one pound of fat contains roughly 3,500 calories of energy. If you cut 500 calories a day, by the end of seven days, you’ve reached that 3,500 mark. Boom. One pound gone.

But wait.

Human bodies aren't calculators. We aren't closed systems. If you just slash calories blindly, your metabolism might decide to go on strike. This is why some people stop losing weight even when they're eating like a bird. It’s frustrating. It’s confusing. And it’s exactly what we need to break down.

Why the 3,500 Calorie Rule is Kinda Broken

Research from the National Institutes of Health, specifically work led by Dr. Kevin Hall, has shown that the 500-calorie deficit rule is way too simplistic. It assumes your body weight doesn't change as you lose. But it does. As you get smaller, you actually need fewer calories to exist.

If you start at 250 pounds and drop to 200, your heart, lungs, and muscles don't have to work as hard to move you around. Your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) drops. So, that 500-calorie deficit you started with? It's not a 500-calorie deficit anymore. It might only be a 200-calorie deficit now.

This is the "plateau" everyone talks about.

To figure out how many calories to lose a day to lose weight, you first have to know your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). This is the sum of everything: your BMR (calories burned just staying alive), the thermic effect of food (digesting what you eat), and your activity level.

If your TDEE is 2,400 calories and you eat 1,900, you're in a deficit. If you eat 2,500, you're in a surplus. It’s math, but the variables are always shifting.

The Problem With Aggressive Deficits

I’ve seen people try to cut 1,000 calories a day. They want results yesterday. I get it. But here’s the reality: your body is a survival machine. If it thinks it’s starving, it will protect you. It starts by down-regulating "non-essential" processes. You might feel colder. You’ll definitely feel grumpier. You might stop fidgeting—this is called NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis), and it can account for hundreds of burned calories a day. When you're in a massive deficit, your brain subconsciously tells you to sit still to save energy.

🔗 Read more: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

You end up burning less, which cancels out the calories you didn't eat. It’s a losing game.

Realistic Targets: How Many Calories Should You Actually Cut?

For most people, a deficit of 250 to 500 calories per day is the sweet spot.

Why so small?

Because it’s sustainable. You can still go to dinner with friends. You can still have cream in your coffee. You don't have to feel like a prisoner to your tracking app. If you aim for a 500-calorie deficit, you’re looking at about a pound of weight loss a week. For someone with a lot of weight to lose, this might be slightly higher. For someone who is already lean and just trying to lose those last five pounds, a 250-calorie deficit is much safer to prevent muscle loss.

Think about it this way.

If you cut 500 calories, you're essentially removing one large snack or a small meal from your day. Or, better yet, you're eating 250 calories less and moving 250 calories more. That’s a brisk 45-minute walk and skipping the mayo on your sandwich. It’s doable.

Muscle Matters More Than You Think

When you ask about how many calories to lose a day to lose weight, you’re usually talking about fat loss. But the scale doesn’t know the difference between fat, muscle, and water.

If you cut calories too low—let's say you're only eating 1,000 calories a day—your body will start breaking down muscle tissue for energy. This is a disaster for your metabolism. Muscle is metabolically active. It burns calories even while you're sleeping. Losing muscle makes it harder to keep the weight off in the long run.

This is why protein intake is non-negotiable.

Even in a deficit, you should aim for about 0.7 to 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight. This signals to your body: "Hey, keep the muscle, burn the fat instead."

💡 You might also like: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

Tracking: Is It Actually Necessary?

Some people hate calorie counting. I totally get that. It can feel obsessive. But honestly, if you've never done it, you probably have no idea how much you're actually eating.

Studies consistently show that humans are terrible at estimating portions. We underestimate our intake by about 30% to 50% on average. That "handful" of almonds? It’s probably 200 calories, not 50. That "splash" of olive oil? That’s 120 calories right there.

You don't have to track forever. Do it for two weeks. Treat it like a science experiment. Use an app like Cronometer or MyFitnessPal. Get a food scale—it’s more accurate than measuring cups. Once you see what 500 calories actually looks like, you can start "intuitive eating" with a lot more accuracy.

The Role of Exercise (And the Trap)

You can't out-run a bad diet. You’ve heard it before because it’s true.

A 30-minute run might burn 300 calories. A single blueberry muffin from a coffee shop can be 450 calories. It takes seconds to eat the muffin and a long, sweaty time to burn it off.

Exercise should be for health, strength, and mental clarity. It’s a "bonus" for your calorie deficit, not the primary driver. If you rely solely on exercise to create your deficit, you’ll likely end up "compensatory eating"—you're so hungry from the gym that you eat back all the calories you burned, and then some.

Sustainable Strategies for a 500-Calorie Deficit

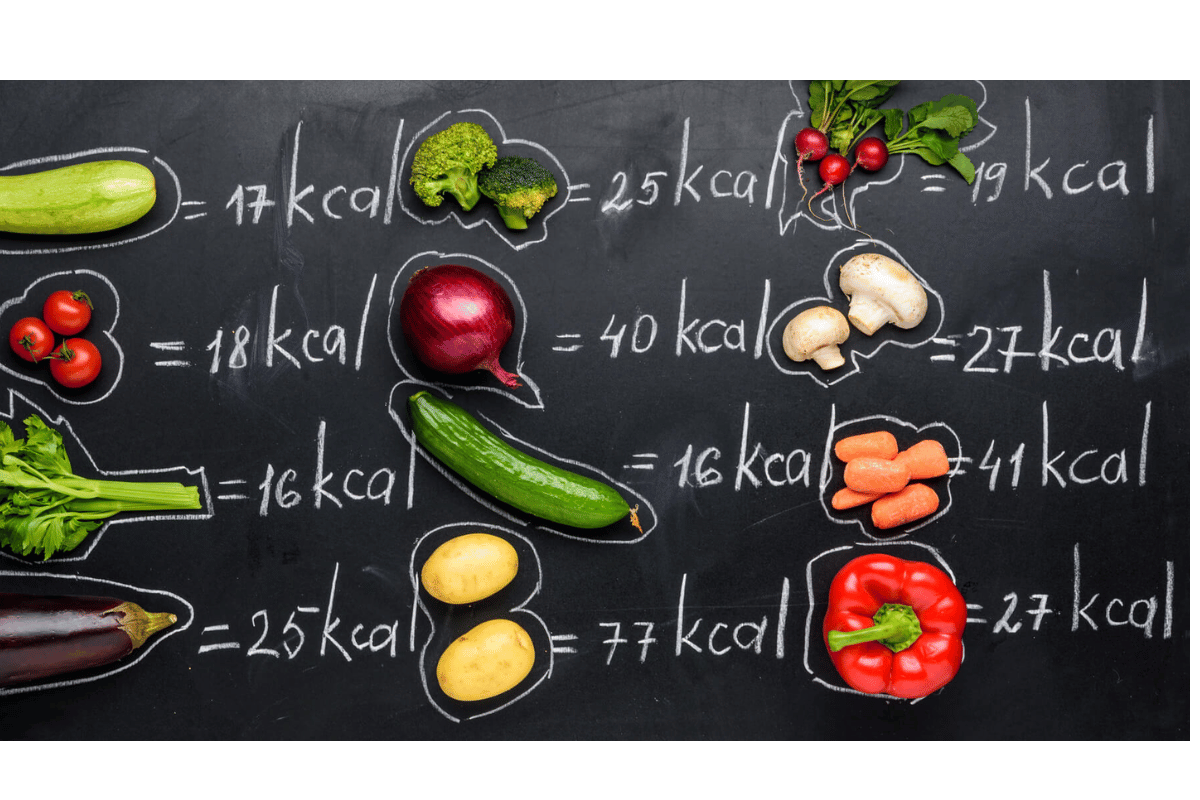

Instead of just "eating less," focus on "eating better." It sounds like a cliché, but volume eating is a literal game-changer.

You can eat a giant bowl of spinach, cucumbers, and peppers for about 50 calories. Or you can eat a single tablespoon of peanut butter. Which one is going to keep you full for two hours?

- Focus on Fiber: Fiber slows down digestion. It keeps you full. Beans, lentils, berries, and cruciferous vegetables are your best friends here.

- Drink Water First: Sometimes thirst masks as hunger. Drink a large glass of water 20 minutes before a meal. You'll likely eat less.

- The Protein Anchor: Every meal should have a protein source. Chicken, tofu, Greek yogurt, eggs—doesn't matter. Protein triggers the release of satiety hormones like peptide YY.

- Sleep is a Cheat Code: If you're sleep-deprived, your ghrelin (hunger hormone) spikes and your leptin (fullness hormone) crashes. You will crave sugar. You will want to blow your calorie budget. Seven hours is the bare minimum.

The Mental Side of the Deficit

Let's be real. Being in a calorie deficit isn't always fun. There will be days when you’re hungry. There will be days when the scale doesn't move, or even goes up because you had a salty meal and your body is holding onto water.

This is where most people quit.

📖 Related: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

Weight loss is not linear. It looks like a jagged line pointing downward. You might stay at 180 pounds for ten days, then wake up at 177. This is called the "whoosh effect." Your fat cells fill up with water as the fat leaves, and then eventually, the body lets that water go.

If you're asking how many calories to lose a day to lose weight, you’re asking for a plan. But the plan only works if you stick to it when it gets boring. Consistency beats intensity every single time.

A 300-calorie deficit that you maintain for six months is infinitely better than a 1,000-calorie deficit you maintain for six days before face-planting into a pizza.

Practical Steps to Start Today

Don't try to change everything at once. Pick a path.

First, find your maintenance calories. You can find TDEE calculators online easily. Use the "sedentary" setting even if you work out a few times a week—most people overestimate their activity level.

Once you have that number, subtract 300 to 500. This is your target.

If your maintenance is 2,200, try eating 1,800.

For the first week, don't worry about "perfect" food. Just hit the number. In the second week, try to hit your protein goal within that number. In the third week, start adding more whole foods and vegetables.

If you lose more than two pounds a week, you might be cutting too hard. Slow down. If you lose nothing after three weeks, your "maintenance" estimate was likely too high, or your tracking is off. Adjust by another 100-200 calories and see what happens.

Weight loss is a series of small adjustments. It’s not a one-time decision. You’re essentially learning how to fuel a new, smaller version of yourself. Take it slow, stay honest with your logging, and remember that your body isn't an enemy to be defeated—it's a system to be managed.

Focus on the trend, not the daily fluctuation. If you’re consistently in that deficit, the results are inevitable. It’s just physics.

Key Takeaways for Success:

- Calculate your TDEE based on a sedentary lifestyle to avoid overestimation.

- Aim for a modest 250-500 calorie deficit to preserve muscle and sanity.

- Prioritize protein (0.7-1g per pound) to keep your metabolism firing.

- Use a food scale for at least two weeks to calibrate your internal "portion sensor."

- Measure progress by weekly averages, not daily scale weight.

- Increase daily movement (NEAT) through walking rather than relying solely on high-intensity gym sessions.

- Ensure 7-8 hours of sleep to keep hunger hormones in check.