You’ve seen the number 2,000. It's plastered on every cereal box and nutrition label in the grocery store. It’s the "gold standard" for the average human, or so the FDA says. But honestly? That number is almost entirely useless for you specifically. If you’re trying to figure out how many calories should you be eating to lose weight, you’ve likely realized that a 5'2" accountant who enjoys knitting doesn’t need the same fuel as a 6'4" construction worker who hits the gym three times a week.

Weight loss isn't a math problem you can solve with a single, static number. It's more like trying to hit a moving target while standing on a boat. Your body is smart. It’s adaptable. It’s also incredibly stubborn about keeping the fat it has.

The Math Behind the Maintenance

Before you can lose anything, you have to know your "zero point." This is your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). Think of it as the cost of keeping the lights on in your body. It’s the sum of your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)—what you burn just existing—plus the energy you use to digest food and move around.

Most people overestimate their activity level. They do. It’s human nature. You go for a 20-minute walk and feel like you’ve earned a pizza. In reality, that walk burned maybe 100 calories. That’s a medium apple. If you want to get serious about how many calories should you be eating to lose weight, you need to start with a realistic look at your current intake.

Track everything for three days. Don't change a thing. Just observe. If you’re maintaining your weight on 2,500 calories, then your "deficit" starts there. Subtracting 500 calories a day from that maintenance level is the classic advice because, theoretically, 3,500 calories equals one pound of fat.

But it's rarely that linear.

The Mifflin-St Jeor equation is generally considered the most accurate formula for modern humans, but even that has a margin of error. It looks like this:

$$10 \times \text{weight (kg)} + 6.25 \times \text{height (cm)} - 5 \times \text{age (y)} + s$$

In this formula, $s$ is +5 for males and -161 for females. Once you have that BMR, you multiply it by an activity factor ranging from 1.2 (sedentary) to 1.9 (extremely active).

Why the 1,200 Calorie Rule is Usually a Bad Idea

You’ve probably heard that 1,200 calories is the floor. It’s the magic number often touted in diet magazines. For most adults, 1,200 calories is basically starvation.

👉 See also: Chandler Dental Excellence Chandler AZ: Why This Office Is Actually Different

When you drop your intake too low, your body doesn't just "burn fat." It panics. It starts downregulating non-essential processes. Your hair might get thinner. You feel cold all the time. Your "NEAT"—Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis—tanks. This means you stop fidgeting, you move slower, and you subconsciously sit down more often because your brain is trying to save energy.

Kevin Hall, a lead researcher at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has done fascinating work on this. His studies, including those on "The Biggest Loser" contestants, show that extreme caloric restriction can lead to metabolic adaptation that lasts for years. Their bodies essentially fought back against the weight loss by becoming hyper-efficient.

Protein: The Non-Negotiable Lever

If you are cutting calories, protein is your best friend. Period.

When you're in a deficit, your body looks for fuel. It’s not picky. It will gladly chew through your hard-earned muscle tissue if it’s easier than mobilizing fat stores. Muscle is metabolically expensive; fat is just storage. Your body wants to ditch the expensive stuff first.

By keeping protein high—typically around 0.7 to 1 gram per pound of goal body weight—you signal to your body that it needs to keep that muscle. Plus, protein has a higher "thermic effect of food" (TEF). You actually burn more calories digesting a steak than you do digesting a bowl of pasta.

The Stealth Saboteurs

You can track every morsel and still fail if you don't account for the "hidden" stuff. Oils are the big one. A tablespoon of olive oil is 120 calories. If you're "eyeballing" your salad dressing, you might be adding 300 calories without even noticing.

Then there's the weekend.

Many people are perfect from Monday to Friday. They hit their target of 1,800 calories every single day. Then Saturday hits. A couple of drinks, a brunch, a late-night pizza. Suddenly, they’ve consumed 4,000 calories in a day. That surplus doesn't just reset for the week; it averages out. If you eat a 500-calorie deficit for five days (-2,500) but eat a 2,000-calorie surplus on Saturday and Sunday (+4,000), you are actually in a net surplus. You will gain weight.

It’s frustrating. It feels unfair. But the scale doesn't care about your Friday night intentions.

✨ Don't miss: Can You Take Xanax With Alcohol? Why This Mix Is More Dangerous Than You Think

Moving Beyond the Number

How many calories should you be eating to lose weight is a question about biology, but also about psychology. If your "perfect" number makes you miserable, you won't stick to it.

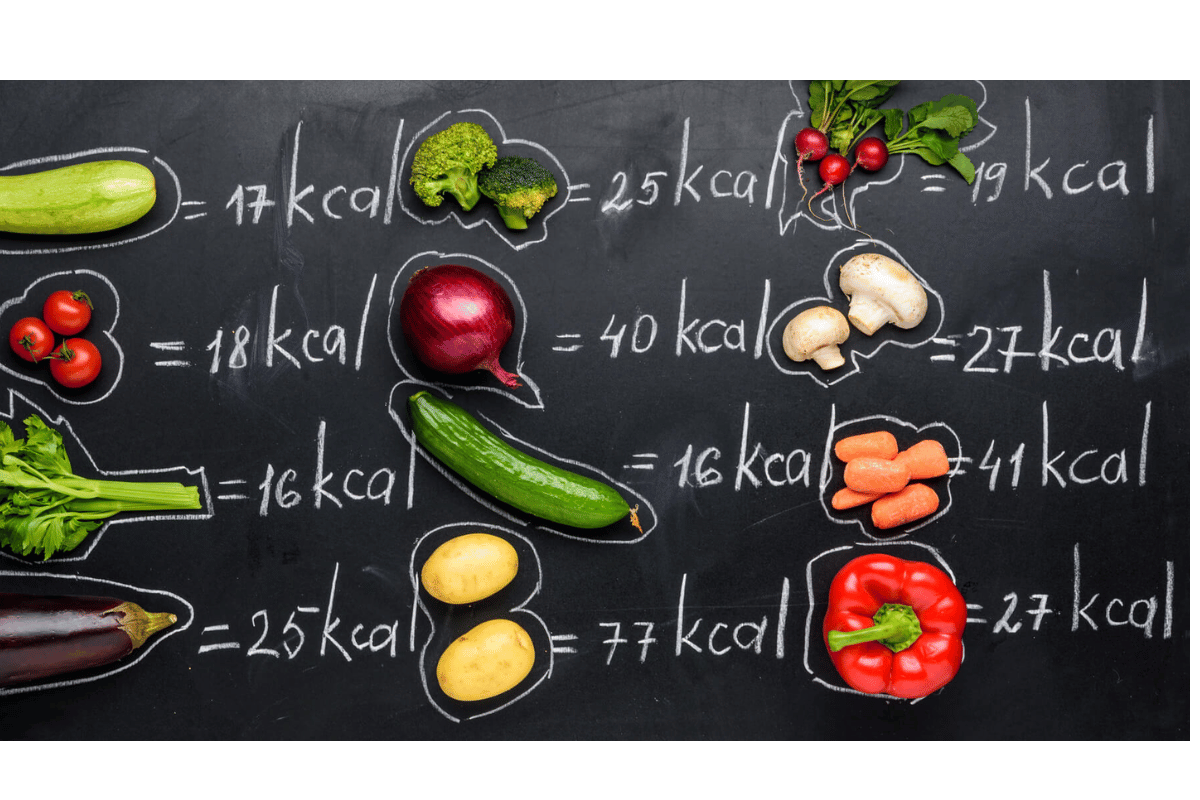

There is a concept called "Volume Eating." It's basically the art of eating massive amounts of low-calorie food—like leafy greens, zucchini, and berries—to trick your stomach's stretch receptors into thinking you’re full. You can eat a giant bowl of cauliflower rice for a fraction of the calories in a small scoop of white rice.

Is it the same? No. Does it work? Absolutely.

The Role of Fiber and Satiety

Calories are a measure of heat, not a measure of fullness. 200 calories of jelly beans will leave you hungry in twenty minutes. 200 calories of broccoli is a mountain of fiber that will keep you busy for a while.

When you're planning your intake, focus on fiber-rich carbohydrates. Think beans, lentils, and oats. These slow down digestion and prevent the insulin spikes that can lead to "hangry" episodes an hour after lunch.

Adjusting as You Shrink

Here is the part most people miss: as you lose weight, you actually need fewer calories to maintain that new weight. A 250-pound person requires more energy to move through space than a 200-pound person.

If you started your journey at 2,200 calories and lost twenty pounds, you might hit a plateau. That's not because your metabolism is "broken." It’s because you are now a smaller human being who requires less fuel. You have to adjust your targets every 5-10 pounds to keep the needle moving.

Real Talk on "Starvation Mode"

People love to blame "starvation mode" for why they aren't losing weight.

Let's be clear: starvation mode is largely a myth in the way most people use it. You cannot defy the laws of thermodynamics. If you are truly in a caloric deficit, you will lose weight. However, metabolic adaptation is real. Your body will get slightly more efficient, and you will move less.

🔗 Read more: Can You Drink Green Tea Empty Stomach: What Your Gut Actually Thinks

If you feel like you're eating "nothing" and still not losing weight, you are likely either:

- Underestimating your intake (liquid calories, oils, "bites" of food).

- Overestimating your calorie burn from exercise.

- Dealing with significant water retention (cortisol from stress can cause this).

How to Set Your Actual Target

Stop looking for a magic number on a chart. Instead, follow this sequence:

First, find your maintenance. Eat like you normally do for a week, track it, and see if the scale moves. If it stays the same, that’s your baseline.

Second, subtract 250 to 500 calories from that baseline. This is a "conservative" cut. It’s sustainable. It won't make you want to punch a wall by 3:00 PM.

Third, prioritize 25-30 grams of protein at every meal. This keeps your hunger hormones (like ghrelin) in check.

Fourth, monitor for two weeks. The scale might jump around due to water, so look at the weekly average. If the average is going down, stay the course. Don't drop calories further just because you're impatient.

Finally, plan for "refeed" days or maintenance breaks. Every 8-12 weeks, eat at your maintenance level for a full week. This helps reset your hormones, specifically leptin, which tells your brain you aren't actually starving in the woods. It's a mental and physiological reset that prevents burnout.

Weight loss is a marathon where the finish line keeps moving. You don't need a perfect plan; you need a plan you can actually follow on your worst day, not just your best day.

Actionable Steps for Success

- Buy a digital food scale. Eyeballing a portion of peanut butter is a recipe for accidental weight gain. One "tablespoon" is often actually two.

- Prioritize sleep. Research from the University of Chicago found that when dieters cut back on sleep, the amount of weight they lost from fat dropped by 55%, even if their calories stayed the same. Lack of sleep makes you crave sugar and lowers your willpower.

- Drink water before meals. It's a cliché for a reason. Often, thirst is masked as hunger.

- Don't drink your calories. Soda, lattes, and juice don't register the same way solid food does in your brain. You’ll consume 500 calories and still feel empty.

- Focus on the "Big Wins." Don't stress over whether you ate an apple or an orange. Stress over the fact that you ordered takeout three times this week. Fix the big patterns first.