You've probably spent twenty minutes staring at a treadmill screen, watching those little red numbers crawl toward 300. You're sweating. Your lungs are burning. You think, "This is it. I’m finally hitting the magic number." But then you go home, eat a single slice of avocado toast, and realize you just "ate back" every single bit of that effort. It's frustrating. Honestly, the whole conversation around how many calories should burn a day to lose weight is usually focused on the wrong things. We talk about "burning" as if it only happens at the gym.

That’s a mistake.

The truth is your body is a calorie-burning furnace even when you’re binge-watching a show on the couch. Every breath, every heartbeat, and even the process of digesting your dinner requires energy. If you want to lose weight, you have to stop looking at exercise as the only lever you can pull. It's a piece of the puzzle, sure, but it's not the whole picture.

The Math Behind the Burn

To figure out how many calories should burn a day to lose weight, we have to talk about Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). This isn't just a fancy acronym. It’s the sum of everything your body does.

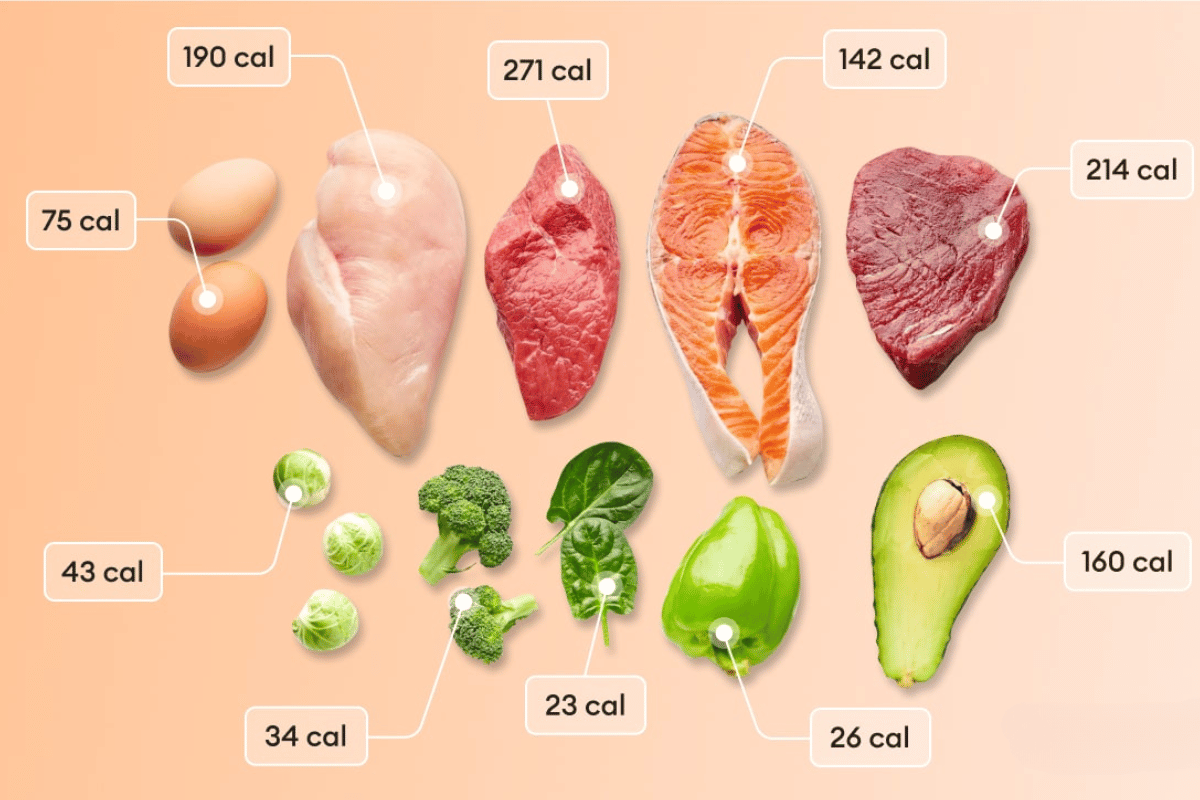

First, there’s your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR). Think of this as the cost of keeping the lights on. If you stayed in bed for 24 hours without moving a muscle, you’d still burn a significant amount of energy. For most people, BMR accounts for about 60% to 75% of their total daily burn. Then you have the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF). Yes, you actually burn calories just by eating and processing nutrients. Protein has a higher TEF than fats or carbs, which is why bodybuilders are always carrying around chicken breasts.

Then comes the part most people obsess over: physical activity. This is split into two categories. There's EAT (Exercise Activity Thermogenesis), which is your intentional workout. And then there's NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis). NEAT is the secret weapon. It’s fidgeting, walking to the mailbox, standing while you take a phone call, or cleaning the kitchen.

If you want to lose one pound of fat, the traditional wisdom—based on the Max Wishnofsky rule from 1958—says you need a deficit of about 3,500 calories.

Is that perfectly accurate? Not really.

Newer research, like the studies coming out of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, suggests that as you lose weight, your body fights back. Your metabolism slows down to protect you from what it perceives as "starvation." This is why a simple 500-calorie daily cut doesn't always result in exactly one pound lost per week indefinitely.

✨ Don't miss: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

Finding Your Personal Number

So, let's get specific. How many calories should burn a day to lose weight specifically for you?

Most experts, including those at the Mayo Clinic, suggest that a safe and sustainable rate of weight loss is 1 to 2 pounds per week. To hit that, you generally need to create a daily deficit of 500 to 1,000 calories.

But wait.

If your TDEE is 2,200 calories and you try to "burn" 1,000 calories through exercise alone every day, you are going to burn out in less than a week. It’s physically exhausting. Instead, the "burn" should be a combination of eating less and moving more.

For example, you might reduce your food intake by 300 calories (maybe skip the soda and the extra cheese) and increase your physical activity to burn an extra 200 calories. That gets you to that 500-calorie deficit without feeling like you’re training for a marathon.

The Role of Muscle Mass

Muscle is metabolically "expensive." Fat is cheap.

If you have more muscle, your BMR goes up. This means you burn more calories while you’re sleeping. This is why resistance training is often more effective for long-term weight loss than steady-state cardio. When you run on a treadmill, you burn calories while you’re running. When you lift heavy weights, you create micro-tears in your muscles that require energy to repair for hours afterward. Plus, you’re building the engine. A bigger engine burns more fuel.

Why the "Calories Burned" Trackers are Lying to You

You know that Apple Watch or Fitbit you’re wearing? It’s probably wrong.

🔗 Read more: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

A study from Stanford University found that even the best fitness trackers can be off by as much as 27% to 93% when estimating calories burned during exercise. They are great for tracking steps and heart rate trends, but if your watch says you burned 500 calories in a spin class, take it with a massive grain of salt.

If you rely solely on those numbers to decide how much you can eat later, you’ll likely overeat. This is a trap called "compensatory eating." You think, "I burned 600 calories, so I can totally have this muffin." In reality, you probably burned 350, and the muffin is 450. Suddenly, your deficit is gone.

NEAT: The Underrated Variable

If you’re wondering how many calories should burn a day to lose weight, don’t ignore the "boring" movement.

James Levine, a researcher at the Mayo Clinic, has done extensive work on NEAT. He found that lean people tend to stand and move about 2.25 hours more per day than people with obesity. They aren't necessarily "working out" more; they just aren't sitting as much.

Think about it.

If you spend an hour at the gym but sit at a desk for eight hours and on a couch for four, you are "sedentary with a workout." Your total daily burn might actually be lower than someone who never goes to the gym but spends their day gardening, walking to meetings, and pacing while they talk.

The Danger of Too Great a Deficit

There is a point of diminishing returns.

If you try to burn too many calories or eat too few, your body enters a state of metabolic adaptation. Your levels of leptin (the fullness hormone) drop, and your levels of ghrelin (the hunger hormone) skyrocket. You become lethargic. Your body starts breaking down muscle for energy because muscle is "wasteful" when food is scarce.

💡 You might also like: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

This is why "crash diets" almost always end in weight regain. You aren't just losing fat; you're lowering your BMR. When you eventually go back to eating "normally," your body is now burning fewer calories than it was before you started the diet.

Practical Strategies for a Sustainable Burn

Stop overcomplicating it. You don't need a lab-grade calorimeter to lose weight.

Start by finding your maintenance calories. Use an online TDEE calculator as a starting point. Eat that amount for two weeks and track your weight. If your weight stays the same, that’s your baseline.

Now, subtract 250 to 500 from that number.

To boost the "burn" side of the equation without killing yourself at the gym:

- Prioritize Protein: It keeps you full and uses more energy to digest. Aim for 0.7 to 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight.

- Walk 8,000 to 10,000 steps: It sounds cliché, but it works because it doesn't spike your hunger like high-intensity intervals often do.

- Lift weights twice a week: Keep the muscle you have so your metabolism stays high.

- Sleep 7-9 hours: Lack of sleep kills your willpower and messes with your insulin sensitivity. It’s hard to burn fat when your hormones are a mess.

Weight loss isn't a math problem you solve once. It's a biological negotiation. Your body wants to stay the same. You have to convince it—slowly and consistently—that it’s okay to let go of stored energy.

Forget the "burn 1,000 calories today" mindset. It's about the cumulative deficit over weeks and months.

Actionable Next Steps

To get started today, calculate your estimated TDEE using the Mifflin-St Jeor equation, which is widely considered one of the most accurate formulas for non-clinical settings. Once you have that number, aim for a modest 15% reduction in total calories. Focus on increasing your daily step count by just 2,000 steps over your current average rather than adding a grueling new cardio routine. This approach minimizes the "starvation" signals to your brain while steadily moving the needle on your fat loss goals. Keep a simple log of your morning weight and weekly averages to see how your body responds, adjusting only after three weeks of consistent data.