Pluto is weird. Seriously. Most people still argue about whether it’s a planet or a "dwarf" planet, but honestly, that’s the least interesting thing about it. If you stood on its icy, nitrogen-covered surface, the sun wouldn’t just rise and set like it does in Chicago or London. It would take forever.

So, how long is a day on Pluto exactly?

It lasts about 153.3 hours.

That is roughly 6.4 Earth days. Imagine a work week that never ends, where the sun hangs in the sky for nearly three full Earth days before finally dipping below the horizon. It’s a slow, sluggish rotation that makes our 24-hour cycle look like a sprint. But the "why" behind this length of time is actually way more fascinating than the number itself.

The strange mechanics of Plutonian time

Time on Pluto isn't just about spinning. It’s about a cosmic dance. On Earth, we have the moon, which is tiny compared to us. Pluto has Charon. Charon is so big compared to Pluto—about half its size—that they are effectively a binary system.

Because they are so close in mass, they are "tidally locked." This is a huge deal. It means Pluto and Charon always face each other with the exact same side. If you were standing on the "back" side of Pluto, you would never, ever see Charon. Not once.

This tidal locking is why the day is so long. The two bodies have settled into a rhythmic, slow-motion spin that takes 6.387 Earth days to complete one full rotation. It’s a physical standoff that has lasted billions of years.

Comparing the neighborhood

To get a sense of how sluggish this is, look at the rest of the solar system. Jupiter is a speed demon, finishing a "day" in about 10 hours. It’s huge but it’s whipping around so fast it actually bulges at the middle. Then you have Venus, which is the ultimate outlier, taking 243 Earth days to spin once—and it spins backward.

✨ Don't miss: Bang & Olufsen News Today: Why the CEO Exit and Beo Grace Are Changing Everything

Pluto sits in that middle ground of "slow but steady."

153 hours.

Think about that. You could fly from New York to Singapore and back several times before the sun sets on Pluto.

What a day actually looks like (The "Noon" problem)

If you're expecting a bright, sunny afternoon, you're going to be disappointed. Pluto is roughly 3.7 billion miles away from the sun. Because of that distance, sunlight is incredibly faint. NASA actually has a "Pluto Time" calculator because, at high noon on Pluto, the light level is about the same as twilight here on Earth—that moment right after the sun goes down but before it gets pitch black.

It’s dim. It’s cold.

The sun itself wouldn't look like a big yellow ball. It would look like an exceptionally bright star. It’s still the brightest thing in the sky, but it doesn't provide the warmth we associate with a "day."

The Nitrogen Cycle

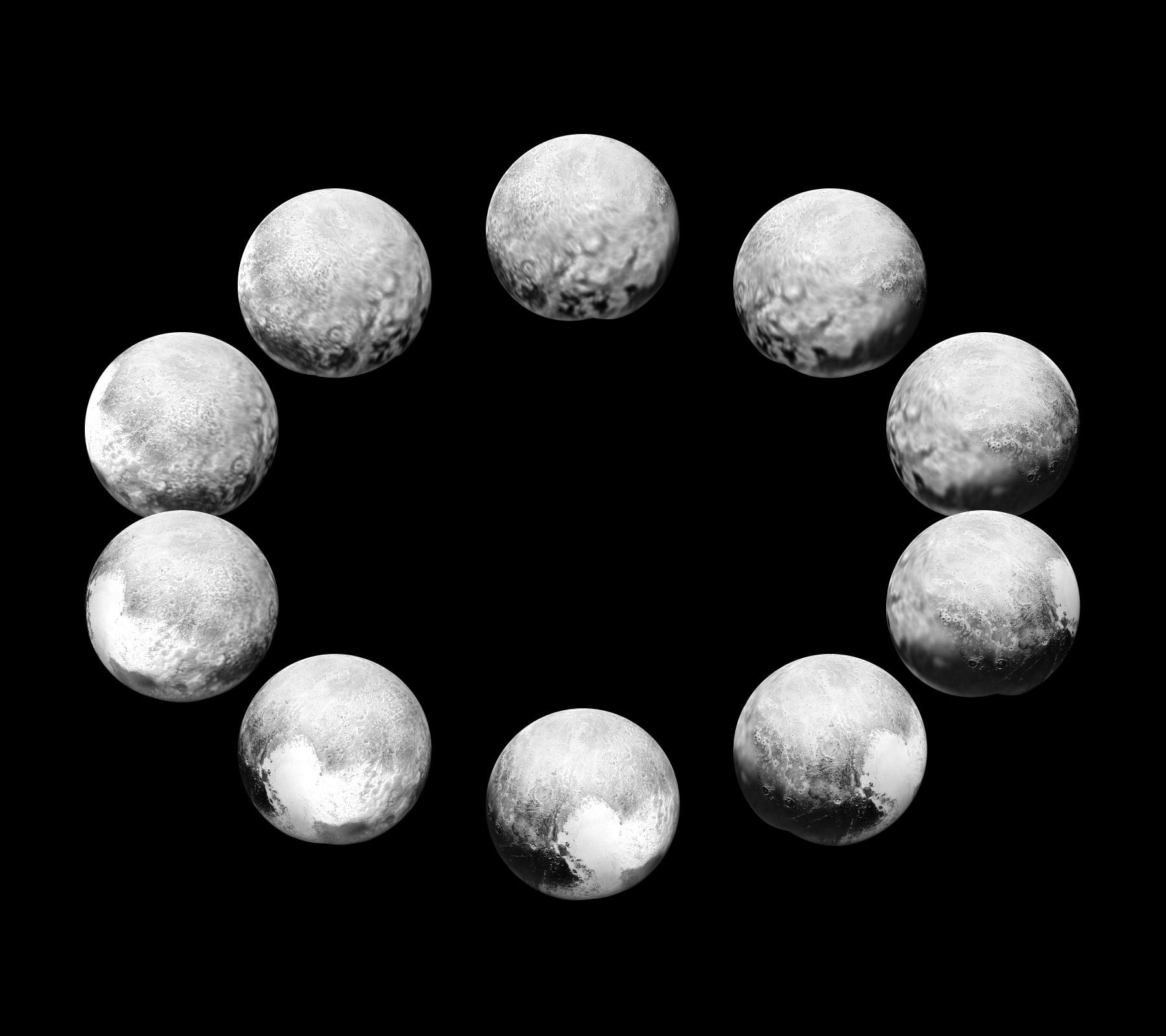

During those long 153 hours of sunlight, things actually happen on the surface. We learned this from the New Horizons mission in 2015. When the sun hits the nitrogen ice, it turns directly into gas—a process called sublimation. This creates a thin, tenuous atmosphere.

When the sun finally sets (after three days of "daylight"), the temperature drops even further. That gas freezes and falls back to the surface as "snow." This cycle happens every single Plutonian day, though it's heavily influenced by Pluto's massive, elliptical orbit which takes 248 years to go around the sun.

Why we got it wrong for so long

Before 2015, we were basically guessing. We used ground-based telescopes and Hubble, but Pluto is tiny and far away. It was just a few pixels.

Scientists like Alan Stern, the Principal Investigator of the New Horizons mission, pushed for decades to get a closer look. When the probe finally zipped past at 36,000 miles per hour, we realized Pluto wasn't just a dead rock. It has "heart-shaped" glaciers (Tombaugh Regio) and mountains made of water ice that are as tall as the Rockies.

These features are shaped by that 153-hour rotation. The slow spin affects how heat is distributed across the "heart," which is actually a massive nitrogen ice plain. If the day were shorter, the weather patterns and ice flows would look completely different.

The mystery of the tilted axis

Another reason the how long is a day on Pluto question gets complicated is the tilt. Earth is tilted at about 23.5 degrees. That’s why we have seasons.

Pluto is tilted at 120 degrees.

It’s basically lying on its side. This means that at certain points in its long year, the poles get decades of continuous sunlight, while the other side is draped in a "day" that lasts for years of darkness. The 153-hour rotation still happens, but if you're at the pole, the sun might just circle the horizon without ever setting.

The Charon Connection again

You can't talk about Pluto's day without talking about the "Barycenter." Because Charon is so heavy, the point they both orbit around isn't inside Pluto. It’s in the empty space between them.

Imagine two ballroom dancers spinning around. If one is much bigger, the center of the spin is inside the big person's body. With Pluto and Charon, they are holding hands and spinning around a spot in the air between them. This dance is what sets the 153.3-hour tempo.

Practical implications for future exploration

If we ever send a lander there—not just a flyby—the day length is a nightmare for solar power. You’d need batteries that could last for 76 hours of darkness in a place where the temperature sits at -380 degrees Fahrenheit.

🔗 Read more: Dyson Gen5detect Absolute: What Most People Get Wrong

Nuclear power (RTGs) is the only way.

The long day also means massive temperature swings for any equipment. Even though "Pluto Time" light is dim, the lack of a thick atmosphere means there’s nothing to trap heat. The transition from the "day" side to the "night" side is a brutal freeze that can crack metal if not handled correctly.

How to experience "Pluto Time" yourself

You don't need a telescope to understand the light levels of a Plutonian day. NASA created a tool that tells you exactly when to go outside to see what "high noon" on Pluto looks like. Usually, it's about 10-15 minutes after sunset or before sunrise on Earth.

Next Steps for Space Enthusiasts:

- Check the NASA "Pluto Time" tool: Enter your location to find the exact minute today when the light outside matches Pluto's brightest hour.

- Study the New Horizons Raw Images: You can access the unprocessed data from the 2015 flyby on the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory website. Look for the "striping" on the surface that indicates how the slow rotation affects ice movement.

- Track the Barycenter: Use a space simulator like Universe Sandbox to visualize how Pluto and Charon orbit a point in space. It’s the best way to understand why the day is 153 hours long instead of 24.

Pluto might be a "dwarf" in name, but its daily cycle is one of the most complex and physically demanding environments in the solar system. It’s a slow-motion world of ice and shadows that defies almost every rule we’ve grown used to on Earth.