Time is weird. On Earth, we’ve got it down to a science—24 hours, a sunrise, a sunset, and a sleep cycle that most of us ignore anyway. But if you hopped on a rocket and headed to our neighbor, the question of how long are days on venus would basically break your watch. It’s not just "longer" than an Earth day. It’s fundamentally broken.

Venus is the rebel of the solar system.

While every other planet spins in one direction, Venus decided to spin backward. It’s called retrograde rotation. Because of this, and its agonizingly slow crawl around its axis, the concept of a "day" becomes a bit of a headache. You see, there are actually two ways to measure a day, and on Venus, they’re both pretty mind-blowing. Honestly, the numbers don't even seem real when you first hear them.

The Sidereal Day vs. The Solar Day

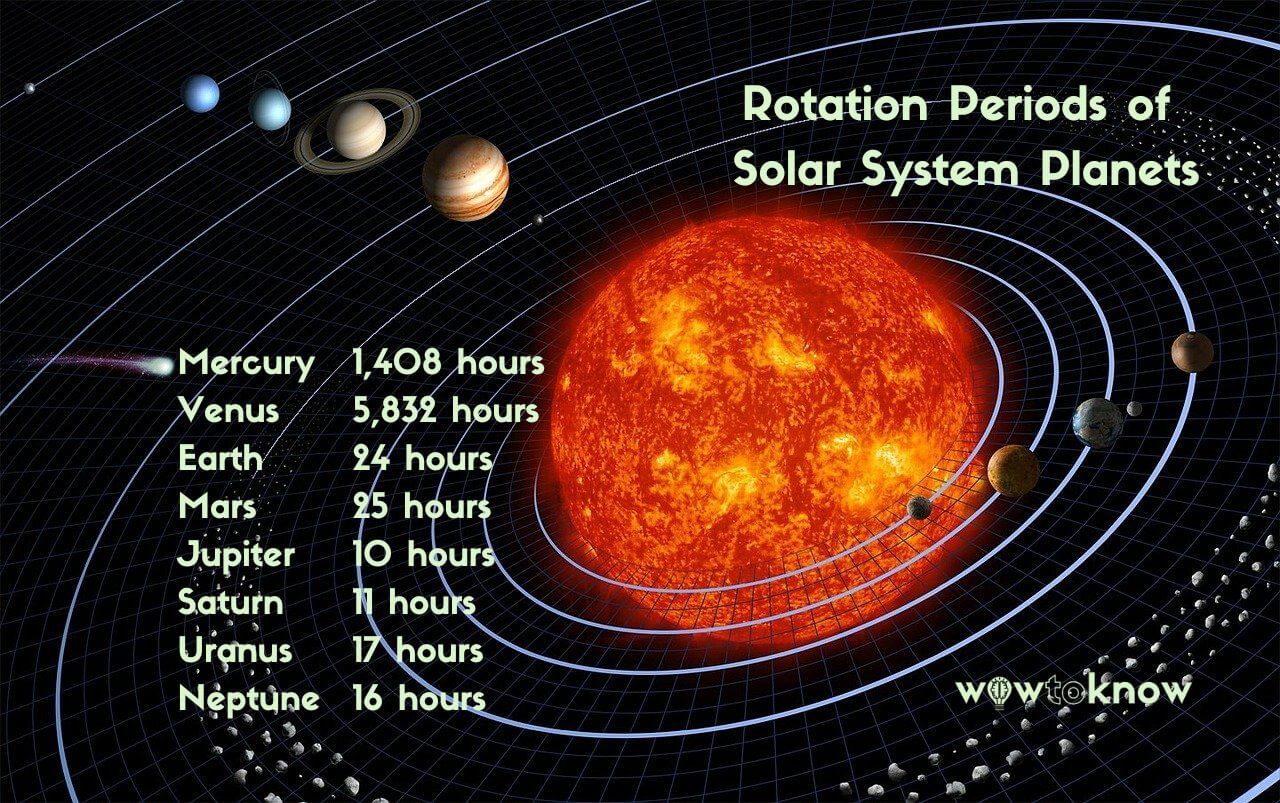

First, let’s talk about the sidereal day. This is the time it takes for a planet to complete one full spin on its axis relative to the stars. On Earth, that’s about 23 hours and 56 minutes. On Venus? It takes 243 Earth days.

Think about that for a second.

A single rotation takes longer than it takes for the planet to orbit the Sun. A year on Venus is only about 225 Earth days. So, technically, a "day" (one rotation) is longer than a year. It's a cosmic quirk that sounds like a typo in a textbook, but NASA’s Magellan mission confirmed these sluggish speeds back in the 90s.

Then there’s the solar day. This is what you’d actually experience if you were standing on the surface—the time from one noon to the next. Because Venus is orbiting the Sun while spinning backward, the Sun would actually rise in the west and set in the east. Even weirder, the solar day is "only" about 117 Earth days. So, while the planet takes 243 days to spin once, the sun comes up every 117 days because of the planet's movement along its orbital path.

Why is Venus So Lazy?

Scientists have been scratching their heads over this for decades. Most planets spin counter-clockwise if you're looking down from the north pole. Venus goes clockwise.

One leading theory involves a massive "big whack." Early in the solar system's history, a protoplanet might have slammed into Venus, flipping it upside down or completely cancelling out its original momentum. Another theory, supported by researchers like Alexandre Correia and Jacques Laskar, suggests it wasn't a crash at all. Instead, it might have been the planet's incredibly thick, soupy atmosphere.

Venus has an atmospheric pressure 90 times greater than Earth's. It's like being 3,000 feet underwater. The Sun's gravity pulls on this heavy atmosphere, creating "thermal tides" that could have acted like a brake, slowing the planet down over billions of years until it started creeping backward.

Life in the Slow Lane (Literally)

If you were standing on the surface—ignoring the fact that you’d be crushed by the pressure and melted by the 900-degree heat—life would be bizarre.

The sun would crawl across the sky. You’d have roughly 58 days of continuous daylight followed by 58 days of pitch-black night. But it wouldn't even look like a "day." The clouds are so thick that you’d never actually see the Sun as a distinct circle. It would just be a hazy, yellow-orange glow that gets slightly brighter and then slightly dimmer over the course of four months.

The Changing Speed of Venus

Here is something most people get wrong: the day length on Venus isn't actually constant.

In 2012, the European Space Agency’s Venus Express orbiter found that the planet was rotating slightly slower than it was when the Magellan spacecraft visited 16 years earlier. The day had stretched by about 6.5 minutes. That sounds small, but in planetary terms, it’s a massive shift in a very short time.

Why the change? It’s likely the atmosphere again.

The winds on Venus are ferocious. While the planet's surface creeps along at about 4 mph (slower than a brisk walk), the upper clouds whip around the planet at 224 mph. This phenomenon is called "super-rotation." The friction between the fast-moving atmosphere and the slow-moving rocky surface can actually transfer momentum, causing the rotation speed to fluctuate.

Measuring the Impossible

Getting an exact measurement for how long are days on venus is a nightmare for engineers. If you're trying to land a rover, like the upcoming DAVINCI+ or VERITAS missions, you need to know exactly where the ground is going to be when you arrive.

Recent studies using Earth-based radar (bouncing radio waves off the planet from the Goldstone Observatory) have finally pinned the average rotation down to 243.0226 days. But even that number is just an average. The planet is constantly "wobbling" because of the tug-of-war between its core and its thick air.

👉 See also: How Much is Windows 10 OS Explained (Simply)

What This Means for Future Exploration

We often call Venus "Earth's Twin" because they're similar in size and mass. But the day length proves they are more like polar opposites. Earth’s fast rotation helps generate a magnetic field that protects us from solar radiation. Venus’s slow spin means it lacks that protective shield.

For future missions, this slow rotation is actually a logistical hurdle. Solar-powered landers would need to survive two months of darkness in a high-pressure oven. Most electronics just give up. This is why most Venus landers, like the Soviet Venera probes, only lasted about an hour or two before being cooked and crushed.

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you're fascinated by the weird mechanics of the Venusian day, here is how you can dive deeper into the data:

- Track the Missions: Keep an eye on NASA's VERITAS and DAVINCI missions, scheduled for the late 2020s and early 2030s. They will use synthetic aperture radar to map the surface with higher precision than ever before, potentially solving the mystery of the fluctuating day length.

- Use NASA's Eyes: You can use the "NASA's Eyes on the Solar System" web tool to see a real-time simulation of Venus's rotation compared to Earth. It visualizes the retrograde spin beautifully.

- Study Atmospheric Torque: If you're into physics, look up papers on "Atmospheric Tides on Terrestrial Planets." It explains the math behind how a gas layer can stop a rocky planet from spinning.

- Check the Radar Data: Visit the JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) archives for radar images of the Venusian surface. Seeing the "pancake domes" and volcanic plains helps put the scale of this slow-moving world into perspective.

Venus reminds us that our 24-hour cycle is a luxury, not a universal rule. In the vastness of space, time is whatever the gravity and the atmosphere decide it is.