If you’ve ever sat in bumper-to-bumper traffic on the 405, knuckles white and heart heavy, you know the feeling. It’s that desperate, clawing need to be literally anywhere else. Guy Clark didn't just feel it; he wrote the manual on how to walk away from it. L.A. Freeway isn't just a country-folk song from the seventies. It’s a blueprint for spiritual survival.

Most people think this song is about hating California. It isn't. Not exactly. It’s about the suffocating pressure of trying to "make it" in a place that doesn't care if you live or die, provided you keep paying the rent. Guy was a luthier—a man who built guitars with his hands—living in a suburban garage in Long Beach. He was a Texas poet trapped in a world of stucco and smog.

✨ Don't miss: Why Rip and Beth Memes Still Dominate Your Feed Even After the Yellowstone Drama

The story goes that Guy and his wife, the brilliant painter and songwriter Susanna Clark, were hitting a wall. The "Land of Milk and Honey" was starting to taste like exhaust fumes. One night, the frustration boiled over. Guy grabbed a burger wrapper—or maybe it was just a scrap of paper, accounts vary depending on who was drinking that night—and scribbled down the lines that would define his career. He wanted out. He wanted the road. He wanted to go home to the high plains.

The Real Story Behind the Lyrics

People get the timeline of L.A. Freeway mixed up. They think Guy wrote it while speeding toward the state line. Honestly? He wrote it while he was still stuck. That’s why it hurts so much. It’s a song of anticipation. It’s the "one foot out the door" anthem for anyone who has ever hated their job or their zip code.

Take that opening line. "Pack up all the dishes." It’s so mundane. It’s domestic. It’s the boring, gritty reality of moving. You don’t just vanish into the sunset; you have to wrap your plates in newspaper first. Guy understood that the physical act of leaving is a chore, but the emotional act is a revolution.

Then there’s the landlord. Oh, the landlord.

"If I can just get off of this L.A. Freeway without getting killed or caught."

That line is pure anxiety. In 1971, when the song was coming together, the Los Angeles freeway system was already a behemoth. To a guy from Monahans, Texas, it must have felt like a concrete labyrinth designed by a madman. The "killed or caught" part isn't just hyperbole. It’s about the fear of being trapped in a life that doesn't fit you until it’s too late to change.

📖 Related: Why Da Dip Still Rules the Dance Floor Thirty Years Later

Jerry Jeff Walker and the Song's Big Break

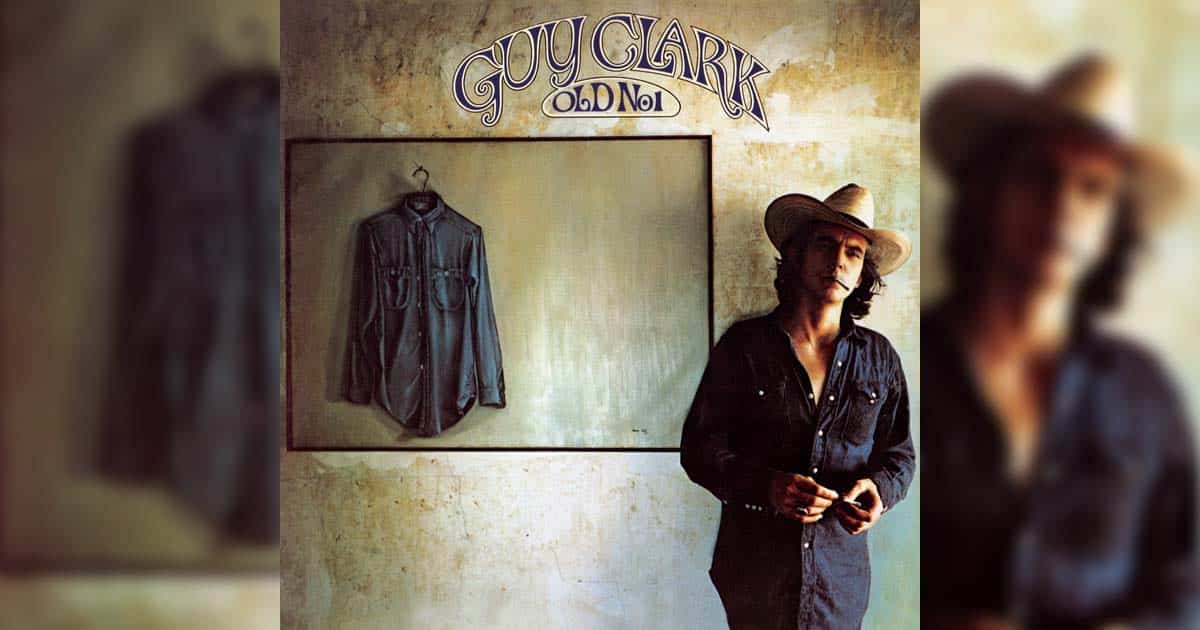

Guy Clark actually recorded his own version for his 1975 masterpiece Old No. 1, but the song hit the stratosphere a few years earlier. Jerry Jeff Walker—the "Mr. Bojangles" guy—cut it in 1972. Jerry Jeff had this wild, loose, slightly drunken energy that made the song feel like a party at the end of the world.

While Jerry Jeff made it a hit, Guy’s version is the one that stays with you. It’s slower. It’s more deliberate. When Guy sings it, you can hear the sawdust on his shirt. You can hear the fact that he actually built those guitars he’s talking about.

There's a specific kind of "Texas-in-Exile" energy to the track. Along with Townes Van Zandt, Guy was part of a movement that valued the "truth" of a lyric over the polish of a production. They weren't interested in Nashville's glitter or L.A.'s pop sensibilities. They wanted songs that smelled like old leather and cedar wood.

Why the Song Still Hits in 2026

You’d think a song about a specific freeway in a specific decade would feel dated. It doesn't. Why? Because the "L.A. Freeway" is a metaphor.

Maybe for you, the freeway is a soul-crushing corporate Slack channel. Maybe it’s a relationship that went south three years ago but you’re still sharing an apartment. We all have a "gate" we’re waiting for the landlord to come out and paint so we can finally leave.

Interestingly, Guy’s wife Susanna once mentioned that the landlord in the song was a real person who was constantly fussing over the property. That detail—the landlord painting the gate—is such a sharp, observational needle. It’s about those tiny, annoying obligations that keep us tethered to places we no longer love.

The Geography of the Song

- Long Beach: Where the struggle actually happened.

- The 405: The likely inspiration for the "freeway" itself, though any major vein out of the city fits.

- Nashville: Where Guy eventually landed and became the "Dean of Nashville Songwriters."

- Texas: The spiritual North Star that pulled him back, even if he didn't live there again.

Guy wasn't a flashy guy. He didn't use big words when small ones would do. He’d spend months—sometimes years—chiseling a single verse until it was perfect. That craftsmanship is why L.A. Freeway sounds as fresh today as it did on a dusty turntable fifty years ago.

Technical Mastery and the "Susanna" Factor

We have to talk about Susanna Clark. She wasn't just his wife; she was his peer. Her paintings grace his album covers, and her influence is all over his writing. In L.A. Freeway, there’s a sense of partnership. "Pack up all the dishes." It’s a "we" song, even if the "we" is implied.

They were part of a circle that included Rodney Crowell, Steve Earle, and Emmylou Harris. This wasn't just music; it was a tribe. When Guy wrote about leaving L.A., he was speaking for a whole group of artists who felt like they were suffocating in the California sun. They needed the humidity of the South or the dry heat of the West to breathe.

Critics often point to the song’s structure as a masterclass in folk writing. It’s simple, but it’s not easy. The rhyme scheme is natural. It never feels forced. It sounds like a conversation you’d have over a beer, which is exactly why it works.

Common Misconceptions

One big myth: Guy hated L.A.

Actually, he appreciated the opportunity, but he hated the vibe. There’s a difference. He didn't write a "diss track." He wrote an exit interview. He recognized that the city offered a lot, but for a man who needed to feel the dirt under his fingernails and the silence of a workshop, L.A. was a sensory overload that blocked his muse.

Another one: People think it’s a "driving song."

💡 You might also like: How Do I Watch Glee: The Honest Truth About Streaming It Right Now

Sorta. But it’s more of a "packing song." If you play it while you’re actually driving, it’s great, but the real power is in the decision to drive. It’s the moment the key turns in the ignition and you realize you never have to come back to this specific parking lot ever again.

How to Truly Appreciate Guy Clark’s Work

If you’re just discovering Guy through this song, don't stop here. You’re scratching the surface of a deep, deep well.

- Listen to Old No. 1 in its entirety. It is widely considered one of the greatest debut albums in the history of any genre. No skips.

- Watch the documentary Without Getting Killed or Caught. It uses Susanna Clark’s diaries to tell the real, messy, beautiful story of their life together. It strips away the myth and shows the man.

- Read the lyrics without the music. Guy was a poet first. See how the words sit on the page. Notice the lack of filler.

- Look up the "Heartworn Highways" film. It captures Guy and his friends in 1975. You can see them sitting around a table, passing a bottle and a guitar. It’s the purest distillation of the scene that produced L.A. Freeway.

The legacy of this song isn't just in the charts. It’s in every songwriter who picks up an acoustic guitar and decides to tell the truth about how hard it is to be a human being in a modern world. Guy Clark taught us that it’s okay to leave. He taught us that home is something you carry with you, usually in a guitar case or a well-worn notebook.

If you're feeling stuck today, put on the track. Listen to that bass line. Feel the momentum. Then, maybe, start packing your own dishes. You don't need a reason to leave a place that doesn't hold your soul anymore. You just need a full tank of gas and the courage to get off the freeway without getting caught.

Next Steps for the Guy Clark Fan:

Go find the 1972 Jerry Jeff Walker version and compare it to Guy's 1975 recording. Notice the difference in tempo and "heaviness." One is a celebration of freedom; the other is a sigh of relief. Understanding that nuance is the key to understanding why Guy Clark remains the gold standard for American songwriting.