Space is mostly empty, dark, and honestly, a bit of a letdown if you’re looking at it with the naked eye. But then the first james webb telescope pictures dropped in July 2022, and suddenly, the "boring" parts of the sky looked like a cosmic jewelry box. It wasn't just about the pretty colors. NASA, ESA, and CSA didn't spend $10 billion just for new desktop wallpapers, though they definitely delivered on that front. The real story is how these infrared snapshots are basically breaking the brains of cosmologists everywhere.

You’ve probably seen the "Cosmic Cliffs" in the Carina Nebula. It’s that orange, mountainous-looking gas cloud that looks like something out of a fantasy novel. Before Webb, the Hubble Space Telescope gave us a great view of it, but it couldn't see through the dust. Webb uses infrared light. It literally peers through the soot to see baby stars forming inside. It’s like turning on night vision in a pitch-black room.

✨ Don't miss: The Speakeasy Internet Speed Check Reality: Why Your Results Might Be Lying

The Science Hiding Behind James Webb Telescope Pictures

When we talk about these images, we have to talk about redshift. Because the universe is expanding, light from the earliest galaxies gets stretched out. By the time that light reaches us billions of years later, it’s no longer visible to our eyes; it has shifted into the infrared spectrum. This is where Webb lives.

Take the SMACS 0723 deep field image. It was one of the first james webb telescope pictures released to the public. If you held a grain of sand at arm's length, that tiny speck of sky is what you're seeing in that photo. Thousands of galaxies. Some of them are warped and stretched into long arcs. That’s gravitational lensing. Massive clusters of dark matter and galaxies are acting like a giant magnifying glass, bending the light of even more distant galaxies behind them. It’s a trick of physics that lets us see further than the telescope should technically be able to see on its own.

Why the "Early Universe" Problem is Stressing Out Scientists

One of the biggest shocks from the Webb data involves the "Impossible Early Galaxies." According to the standard model of cosmology, galaxies in the very early universe—roughly 300 to 500 million years after the Big Bang—should be small, messy, and dim.

They shouldn't be "grown-up" yet.

But Webb found galaxies that are massive. They are bright. They have mature stellar populations. Researchers like Ivo Labbé from the Swinburne University of Technology have noted that these findings might mean our entire timeline for how the universe began is slightly off. We might have to rewrite the textbooks. That’s the power of a single image; it can invalidate decades of theoretical math.

Looking for Water in All the Faraway Places

It’s not just about the deep past. Webb is also looking at exoplanets—planets orbiting other stars. While we don't get "pictures" of these planets in the traditional sense (they usually look like a single pixel or a dip in a light curve), the spectroscopic data Webb provides is essentially a chemical fingerprint.

WASP-96 b is a giant gas planet about 1,150 light-years away. Webb’s "pictures" of its atmosphere—specifically the transmission spectrum—proved there is water vapor, clouds, and haze.

We used to guess. Now we know.

The telescope uses an instrument called NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph) to split the light into a rainbow. Different elements absorb different "colors" of infrared. When we see a specific dip in the light, we know exactly what’s in that planet’s air. Methane? Carbon dioxide? We’re looking for those "biosignatures" that might suggest life, though we haven't found a "smoking gun" for aliens just yet.

📖 Related: Converting 3.9 mm to in: Why This Tiny Measurement Actually Matters

The Pillars of Creation: A Comparison

If you grew up in the 90s, you remember the Hubble photo of the Pillars of Creation. It was iconic. It looked like ghostly fingers of gas reaching into the void.

Webb revisited them.

The difference is staggering. In the Webb version, the pillars look semi-transparent. You can see the fiery red orbs at the edges of the columns—those are "proto-stars." They are only a few hundred thousand years old. They’re basically cosmic toddlers throwing a tantrum, blasting out jets of material that carve through the surrounding gas.

- Hubble sees the "skin" of the nebula (visible light).

- Webb sees the "skeleton" and the "circulatory system" (infrared).

It’s a different way of looking at the same object, and it tells a much more violent, active story of star birth.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Colors

Here’s a secret: the james webb telescope pictures don't actually look like that to the human eye. If you were floating in space next to the telescope, you wouldn't see the vibrant purples and golds. Infrared is invisible to us.

NASA’s visual developers, like Joe DePasquale and Alyssa Pagan, have to "translate" the data. They use a process called "chromatic ordering." They map the longest wavelengths of infrared to red and the shortest to blue.

- Long-wavelength filters (F444W) = Red

- Medium filters (F277W) = Green

- Short filters (F090W) = Blue

It’s not "fake." It’s a translation. It’s like taking a topographical map where height is represented by color. The color represents real, physical data that our biological eyes are just too limited to perceive.

The Tech That Makes the Magic Possible

The telescope is currently orbiting a point called L2, about a million miles away from Earth. It’s cold there. Like, -380 degrees Fahrenheit cold. It has to be that cold because heat produces infrared light. If the telescope were warm, its own heat would "blind" its sensors.

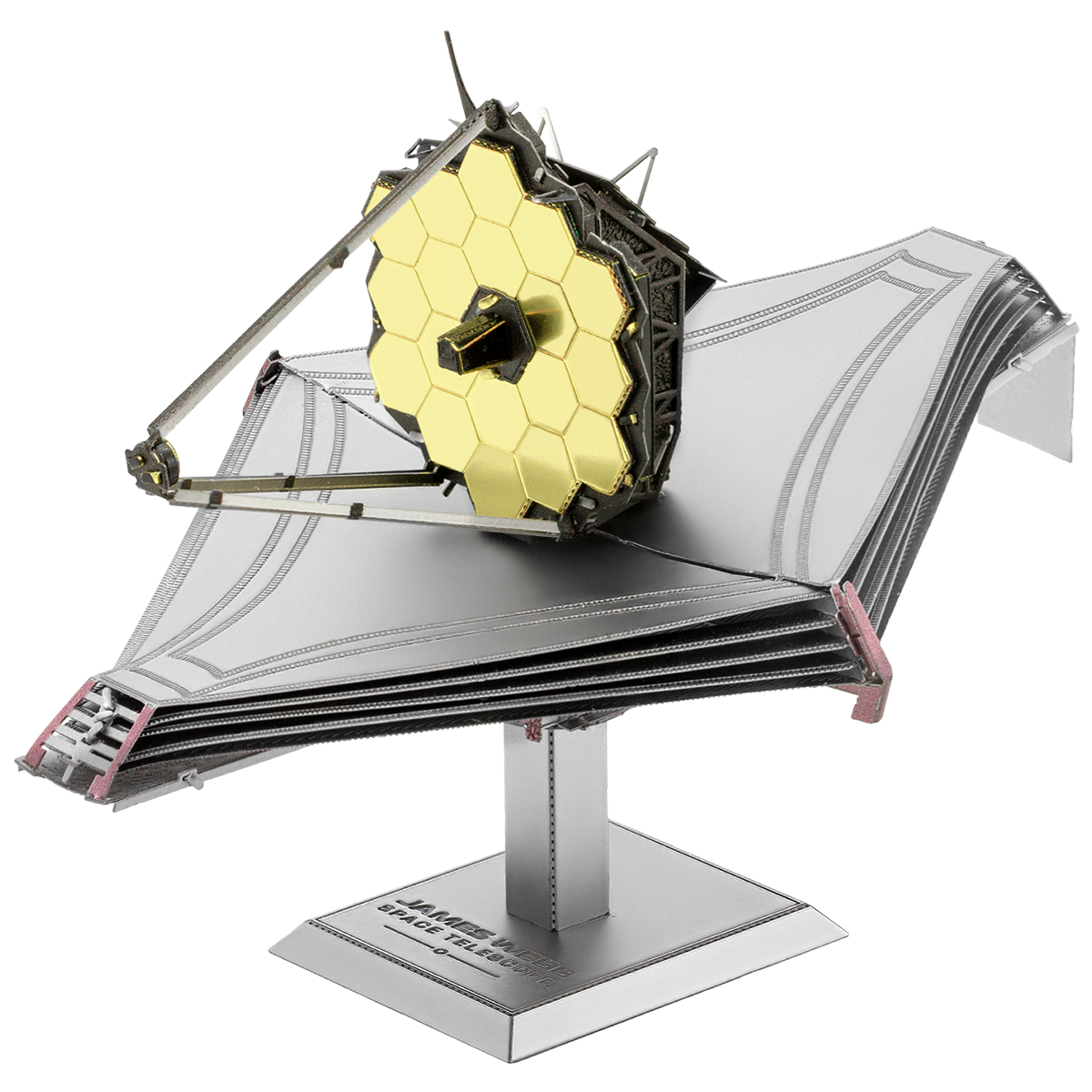

It has a massive sunshield, about the size of a tennis court, made of five layers of Kapton. This shield protects the delicate mirrors from the heat of the Sun, Earth, and Moon.

The gold mirrors? They’re made of beryllium. They’re coated in a layer of gold only 100 nanometers thick. Why gold? Because gold is an incredible reflector of infrared light. It reflects about 99% of the infrared that hits it. Without that gold coating, the images would be blurry and faint.

🔗 Read more: How to lookup a phone number for free without getting scammed by paywalls

Practical Ways to Explore the Data Yourself

You don't need a PhD to dive into this stuff. The raw data is actually public.

If you want to stay updated on the latest james webb telescope pictures, you should check the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST). Most people prefer the curated galleries at WebbTelescope.org, which is fine, but the raw stuff is where the real discoveries happen.

Keep an eye on the "Target of Opportunity" observations. These happen when something unexpected occurs, like a supernova or a comet appearing. The telescope can be pivoted to catch these fleeting moments in high definition.

Your Next Steps for Following the Mission

- Follow the Webb Flashlight: Use the "Where is Webb" tracker on NASA’s site to see exactly what the telescope is looking at in real-time. It’s surprisingly addictive.

- Download High-Res TIFs: Don't just look at low-quality JPEGs on social media. Go to the official ESA/Webb site and download the full-resolution files. Zooming in on a galaxy cluster and realizing every tiny "star" is actually a galaxy with billions of stars is a perspective-shifting experience.

- Check the Transcripts: Look for the James Webb Space Telescope "First Light" papers on ArXiv.org if you want the heavy science. It’s dense, but it explains the "why" behind the "wow."

The mission is expected to last 20 years. We’re only a few years in. We have barely scratched the surface of what this machine can find. Every new image is a data point that helps us understand where we came from and, more importantly, where the entire universe is going. Keep looking up. The pictures are only going to get weirder and more beautiful from here.