You probably don’t think twice about that shaker of Morton’s sitting on your kitchen table. It’s just there. It’s cheap, it’s white, and it makes your fries taste better. But honestly, the story of how is salt mined is a lot more intense than most people realize. We’re talking about massive underground cathedrals of crystal, high-pressure water jets, and ancient oceans that dried up millions of years ago, leaving behind thick veins of "white gold."

Salt isn't just one thing.

Depending on whether you're looking at the pink Himalayan stuff in your grinder or the grit they toss on icy roads in Chicago, the process of getting it out of the earth changes completely. It’s a mix of heavy machinery, chemistry, and sometimes just letting the sun do its thing.

The subterranean world of rock salt mining

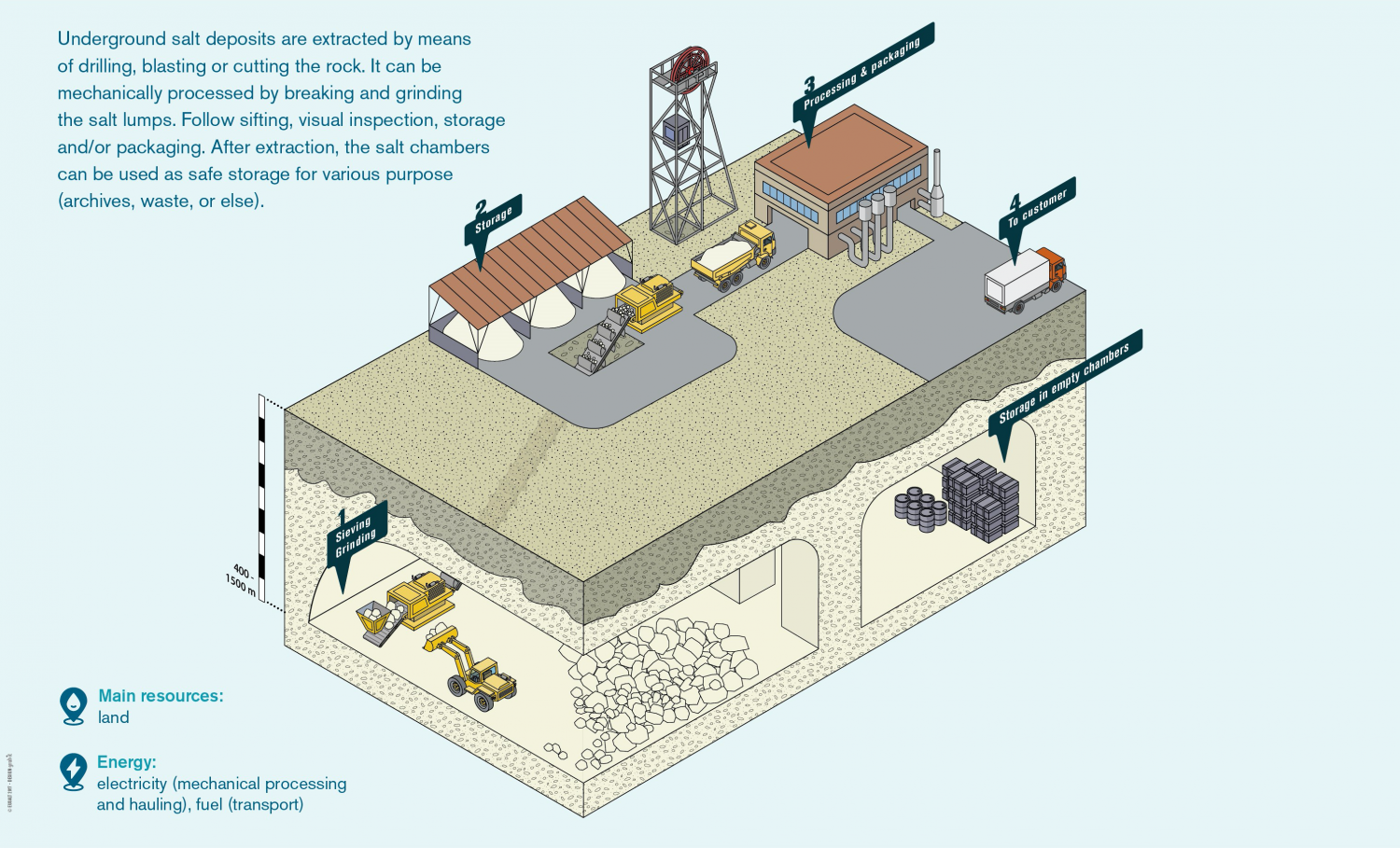

When most people ask how is salt mined, they’re picturing miners with headlamps deep underground. They’re right. This is "dry" mining, or room-and-pillar mining. It’s how we get rock salt (halite).

Imagine a grid of streets carved out of solid salt, hundreds or even thousands of feet below the surface. Miners use massive machines to cut into the salt face. They drill holes, stuff them with explosives, and—boom—the wall collapses into chunks. But they can’t just take it all. If they did, the ceiling would cave in. So, they leave huge pillars of salt standing to hold up the weight of the earth above. It looks like a bizarre, crystalline parking garage.

The scale is hard to wrap your head around. The Goderich mine in Ontario, for example, is the largest in the world. It’s 1,800 feet under Lake Huron. Think about that for a second. There are people driving trucks the size of houses underneath a Great Lake right now.

Once the salt is blasted loose, it’s hauled to a crusher. It gets broken down, loaded onto conveyor belts, and hoisted to the surface. Most of this rock salt isn't for eating. It’s usually too "dirty" with minerals like gypsum or clay. This is the stuff that saves your car from sliding off the road in January.

✨ Don't miss: Is the Dell Inspiron 16 Plus 7640 Actually Worth the Extra Cash?

Solution mining: The "invisible" method

Sometimes, digging a hole is too expensive or the salt is just too deep. That’s when engineers get clever. They use solution mining.

Basically, they drill a well down into a salt deposit. They pump fresh water down one pipe, which dissolves the salt into a super-saturated "brine." Then, they pump that salty liquid back up to the surface. It’s essentially "mining" without ever sending a person underground.

This brine is the backbone of the chemical industry. It’s used to make chlorine, caustic soda, and PVC pipe. But if you want to eat it, you have to get the water back out. This happens in vacuum evaporators. The brine is boiled under pressure, which lowers the boiling point and saves energy. The result? Pure, fine-grained vacuum salt. This is likely what’s in your salt shaker. It’s clean. It’s consistent. It’s efficient.

Solar evaporation is basically ancient history in action

If you’ve ever flown over the San Francisco Bay or parts of the Mediterranean, you’ve seen those weird, bright-colored ponds. Those aren't toxic spills. They're salt pans.

This is the oldest way to do it. You trap seawater in a series of shallow ponds. The sun and wind go to work, evaporating the water. As the water disappears, the salt concentration rises. The ponds change color—from green to a deep, burnt orange—because of certain algae and microorganisms that thrive in high salinity.

Eventually, the salt crystallizes on the floor of the pond. Once it’s thick enough, they drain the remaining liquid (called bitterns) and bring in the harvesters. Companies like Cargill or Morton use this method for a lot of food-grade sea salt.

It’s slow. It takes about five years from the time water enters the first pond until the salt is harvested. You’re at the mercy of the weather. If it rains too much, your harvest is ruined. But the energy cost? Almost zero. The sun does all the heavy lifting.

Why don't we just use seawater for everything?

You’d think seawater would be the easiest source. It’s everywhere. But it’s actually not the most efficient way to get salt for industrial use. Seawater is only about 3.5% salt. The rest is water and other minerals.

Deep underground deposits are much more concentrated. These deposits are the remnants of "evaporite basins"—places where ancient seas were cut off from the ocean and dried up millions of years ago. The Mediterranean Sea almost did this about 5 or 6 million years ago during the Messinian Salinity Crisis. If it had dried up completely, it would have left a salt layer miles thick.

Mining these ancient "trapped" oceans gives us much higher yields than trying to filter current seawater.

The environmental trade-off nobody likes to talk about

Nothing is free. How salt is mined has real consequences.

In solution mining, if you pump out too much salt, you create massive empty caverns. Sometimes these collapse, leading to sinkholes. There have been famous cases, like Lake Peigneur in Louisiana, where a drilling accident caused an entire lake to drain into a salt mine. It created a temporary waterfall and swallowed a drilling rig.

Then there’s the brine disposal. When you’re processing salt, you’re left with highly concentrated salty wastewater. If that leaks into freshwater aquifers, it’s game over for local drinking water.

Gourmet salt: Is it just marketing?

You’ve seen Himalayan Pink Salt. People claim it has "84 trace minerals" and special healing powers.

Let's be real. It’s about 98% sodium chloride. The "pink" comes from iron oxide. Basically, it’s rust.

It’s mined in the Khewra Salt Mine in Pakistan. This is a massive operation, and it’s actually a huge tourist destination. They carve out mosques and statues made of salt. The salt there is "fossil salt" from the Precambrian era. While it looks cool and has a nice crunch, the health claims are mostly just clever branding. You’d have to eat a lethal amount of salt to get any meaningful "mineral" benefits from it.

On the other end, you have Fleur de Sel. This is the "flower of salt" harvested by hand in France (specifically places like Guérande). Workers use wooden rakes to skim the very top layer of salt crystals off the water's surface on calm days. It’s incredibly labor-intensive. That’s why a small jar costs $15 instead of $0.50.

From the face to the factory: The refining process

Raw salt isn't usually ready for your steak. Even the "clean" stuff from solution mining needs a bit of help.

- Anti-caking agents: Salt loves water. If you don't add something like sodium ferrocyanide or calcium silicate, your salt will turn into a solid brick the first time it gets humid.

- Iodization: This was a massive public health win in the 1920s. People in the "Goiter Belt" of the US weren't getting enough iodine, leading to thyroid issues. By adding a tiny bit of potassium iodide to salt, the problem was basically wiped out.

- Washing: Solar salt is washed in a saturated brine solution. This removes impurities without dissolving the salt itself.

How to choose the right salt for the job

Since you now know how is salt mined, you can probably guess that different salts aren't interchangeable.

👉 See also: Why Tracy Kidder The Soul of a New Machine Still Matters Today

- Table Salt: Super fine, very salty, contains iodine. Best for baking where you need it to dissolve evenly in a dough.

- Kosher Salt: The name is a bit of a misnomer; it’s actually "koshering" salt. Its large, flaky crystals are perfect for drawing blood out of meat. Chefs love it because it’s easy to pinch and control. It doesn't have iodine, so it tastes "cleaner" to some people.

- Maldon / Finishing Salt: These are usually pyramid-shaped crystals. They’re meant to be sprinkled on at the very end to give a burst of texture. If you stir them into a soup, you’re just wasting money.

- Pickling Salt: This is pure salt with zero additives. If you use table salt for pickles, the anti-caking agents will make your brine cloudy and the iodine can turn your pickles dark.

Looking ahead: The future of salt

We aren't running out of salt anytime soon. There are trillions of tons of it. But the way we get it is shifting.

Desalination is becoming more common as the world faces water shortages. When we pull fresh water from the ocean, we’re left with a massive amount of brine. Right now, most of that is pumped back into the ocean, which can hurt marine life. In the future, we’ll likely see more "circular" systems where the byproduct of making drinking water becomes our primary source of industrial salt.

It’s a strange thought. The salt you use today might have been part of an ocean that saw the dinosaurs, or it might have been in the Pacific Ocean just a few months ago.

Practical Next Steps for Your Kitchen:

- Check your labels: If you want a cleaner taste for searing steaks, switch to a coarse Kosher salt like Diamond Crystal or Morton Kosher.

- Avoid "cloudy" ferments: If you’re into pickling or making sauerkraut, ensure you’re using "pickling salt" or "sea salt" without anti-caking agents (check the ingredients for sodium ferrocyanide).

- Save the fancy stuff: Keep your expensive Himalayan or Fleur de Sel for the very last step of cooking. Heat destroys the delicate crystal structure you're paying for.

- Consider the source: If you’re buying road salt, look for "treated" varieties that use less total salt to achieve the same de-icing effect—it’s much better for your local soil and waterways.