It is a Tuesday night and you’re staring at the ceiling. You aren't just tired; you're feeling that heavy, suffocating weight on your chest that makes moving your pinky finger feel like a marathon. For years, people just called this "being sad" or "having clinical depression." But for a massive community of artists and patients online, that medical jargon doesn't quite cut it. They’ve started drawing. They’re turning the chemical imbalances in their brains into physical, snarling, often misunderstood creatures.

Visualizing mental disorders as monsters isn't just a weird Tumblr trend from 2013. It’s actually become a legitimate way for people to externalize the internal. When you give the "black dog" of depression a face, it’s no longer you who is the problem. It’s a parasite. It’s a visitor. Honestly, that distinction is probably the most important psychological shift a person can make when they’re struggling to stay afloat.

Why We Started Turning Our Brains Into Beasts

Humans have been doing this forever. Think about the "Mare" in nightmare—a literal goblin sitting on your chest. But modern artists like Toby Allen and Sillvi have taken this to a whole new level. Allen’s "Real Monsters" series went viral because it gave people a vocabulary they didn't have. Instead of saying "I have Generalized Anxiety Disorder," which sounds like a dry insurance claim, people could point to a small, twitchy creature that vibrates so fast it's blurry.

It makes sense. Science is great, but it’s cold.

Dr. Aaron Beck, the father of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), talked extensively about "externalization." The idea is simple: if the disorder is a separate entity, you can fight it. You can't fight your own soul, right? But you can definitely kick a monster out of your house. This shift in perspective is what psychologists call "distancing." It reduces the shame that usually comes with a diagnosis. You aren't "the bipolar person." You are a person who is currently being shadowed by a Bipolar Monster. It’s a subtle linguistic shift that saves lives.

The Anatomy of the Anxiety Beast

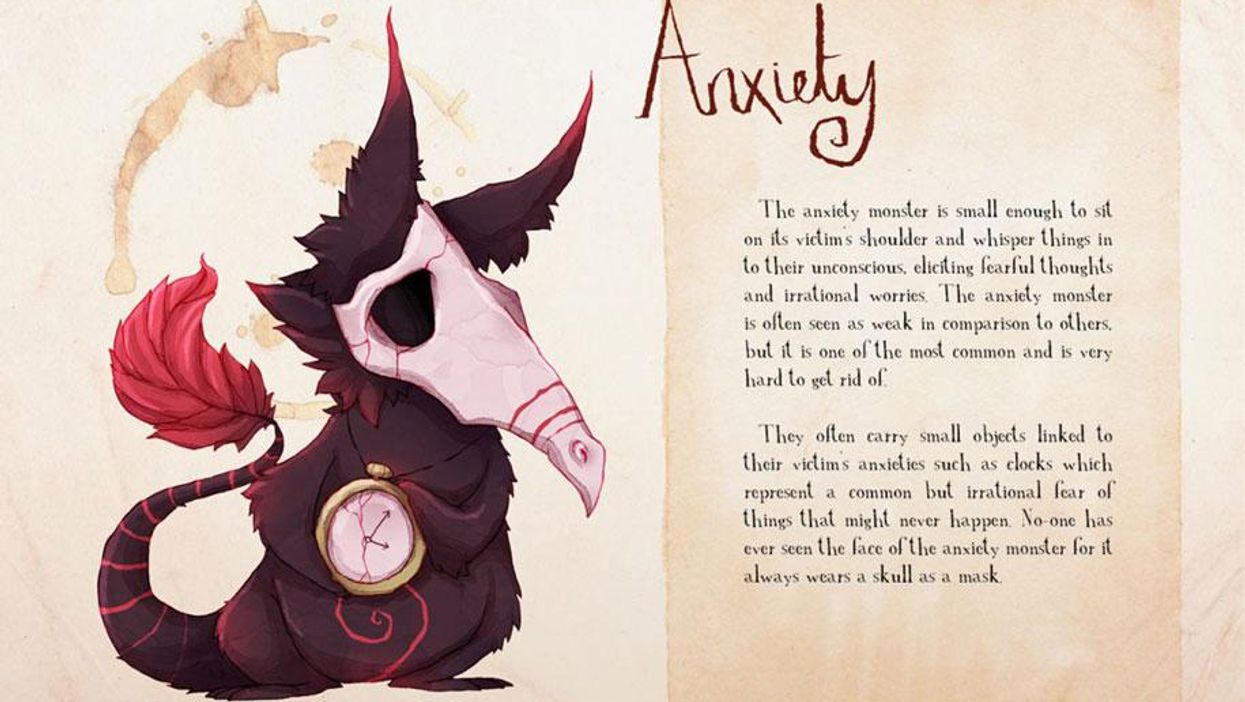

Anxiety isn't just "worry." It’s a physical, visceral reaction. In the world of mental disorders as monsters, anxiety is often depicted as something with too many eyes. Why? Because you feel watched. You feel hyper-aware. Artists often draw it as a small, clammy thing that clings to your neck and whispers "what if" into your ear until your heart rate hits 120.

I remember seeing an illustration where Anxiety was a creature made of static. That hit home for a lot of people. It’s that buzzing in the back of your skull. By giving it a form—maybe something with long, spindly fingers that poke at your nerves—it becomes a tangible opponent. It’s not just "you being dramatic." It’s an evolutionary response gone rogue, personified.

The Problem With Making Pain "Cute"

We have to be careful here. There’s a legitimate critique that turning serious, life-threatening conditions into "monsters" can sometimes romanticize them. If the monster is too cute or "aesthetic," do we stop trying to get rid of it?

Some advocates argue that "monsterfying" illness can oversimplify the biological reality. Schizophrenia isn't just a shadow person; it’s a complex neurological state involving dopamine dysregulation and structural brain changes. A drawing can't capture the nuance of a medication side effect or the grueling reality of a psychotic break.

However, most people using these metaphors aren't trying to replace medicine. They're trying to supplement it. They're looking for a way to explain to their mom or their boss why they can't get out of bed. "The beast is heavy today" is a lot easier to say than "I am experiencing a severe lack of executive function due to a depressive episode."

Depression and the "Black Dog" Metaphor

Winston Churchill famously called his depression his "Black Dog." This is perhaps the most famous example of mental disorders as monsters in history. It wasn't a monster in the sense of a dragon, but a loyal, unwanted companion that followed him everywhere.

Sometimes it’s a dog. Sometimes it’s a void.

In more modern interpretations, the Depression Monster is often huge and slow. It doesn't attack; it just sits on you. It’s a giant, damp blanket that smells like old laundry. It saps the color out of everything. When you see it drawn this way, you realize that the primary symptom isn't sadness—it's exhaustion. It's the weight of the monster's fur.

The Social Impact of Viral Art

When these images go viral on platforms like Instagram or Pinterest, they create "micro-communities." You’ll see comments where people say, "Wait, your monster looks like mine?"

- It reduces isolation instantly.

- It provides a visual "shorthand" for complex feelings.

- It helps kids understand what’s happening to their parents.

- It gives therapists a tool to use with patients who are non-verbal.

I’ve seen therapists use "Monster Journals" where patients draw their symptoms. It’s easier to draw a jagged, sharp creature representing PTSD than it is to describe a flashback. The trauma is often "pre-verbal." It lives in the amygdala, not the language centers of the brain. Art bypasses the logic and goes straight to the feeling.

Avoid the "Stigma" Trap

Let's be real. Stigma is a monster in itself. For a long time, having a mental illness meant you were "crazy" or "weak." Personifying these struggles helps dismantle that. If everyone has a different monster, then having one is just... normal. It’s a part of the human ecosystem.

The artist Sillvi once reimagined psychiatric conditions as characters, and while some found it controversial, it sparked a massive conversation about how we categorize people. Are we our symptoms? No. We are the hosts. And sometimes the host wins.

Practical Ways to Use the "Monster" Concept for Your Own Mental Health

If you're struggling, you don't need to be an artist to use this. It’s a mental framework.

First, give your struggle a name. Not a medical name, a name name. If your social anxiety is a monster named "Gark," then when you’re at a party and feel that tightness in your chest, you can say, "Oh, Gark is being really loud right now." It sounds silly. It is silly. But it breaks the spiral.

Second, describe its physical traits. Is it cold? Is it sharp? Does it have a lot of teeth? Identifying the "sensory" profile of your monster helps you recognize it earlier. If you know the Anxiety Monster always starts by making your hands cold, you can intervene before the full panic attack hits.

Third, figure out what the monster wants. Most "monsters" are actually trying to protect us in a very distorted, prehistoric way. The OCD monster thinks it's keeping you safe by making you check the stove ten times. It's a protector that’s lost its mind. When you realize the monster is just a confused guardian, it’s easier to be kind to yourself.

Moving Beyond the Illustration

The goal of personifying mental disorders as monsters isn't to live with the monster forever. It's to understand it well enough to manage it.

💡 You might also like: What Does a Condom Look Like? The Reality of Different Shapes, Sizes, and Materials

Start by journaling about what your "monster" looked like this week. Did it shrink? Did it grow a new head? This kind of tracking is actually much more effective for some people than traditional mood charts. It captures the vibe of the week, not just a number on a scale of 1 to 10.

Talk to a professional. If you find yourself drawing monsters every day, take those drawings to a therapist. Show them. "This is what my head feels like." It’s the fastest way to get them into your world.

Stop identifying as the illness. You are the person holding the leash, or the person trapped in the cage, or the person fighting the beast. But you are not the beast itself. That distinction is where healing actually starts.

Educate the people around you. Send them a piece of art that resonates with your experience. Say, "This is what I mean when I say I'm 'tired.'" It bridges the empathy gap in a way words rarely do.