You’re breathing it right now. Every lungful of air, every gust of wind, and basically every cloud you’ve ever seen exists within a thin, chaotic blanket of gas wrapped around our planet. But if you're asking how high is the troposphere, you should know there isn't one "magic number" that stays put. It’s a breathing, pulsing layer. It’s actually kinda weird when you look at the physics.

Think of the atmosphere like a sponge. When you heat it up, it expands. When it gets hit by the freezing chill of the poles, it shrivels.

On average? Scientists usually toss out a figure like 7 to 8 miles (roughly 11 to 13 kilometers). But honestly, that’s just a statistical middle ground. If you’re standing at the Equator, the troposphere is a massive, towering dome. If you’re at the North Pole, it’s a cramped, low ceiling that barely clears the highest mountain peaks.

The Latitude Problem: Why Geography Dictates Altitude

The Earth isn't a perfect sphere, and the air certainly doesn't sit on it evenly. The biggest factor in determining how high is the troposphere is where you are standing on the map.

Down at the Equator, the sun is relentless. It beats down, heating the surface and forcing air to rise in massive, powerful convective currents. This pushes the "ceiling" of our weather—the tropopause—way up into the sky. In the tropics, the troposphere can reach heights of 11 to 12 miles (18 to 20 kilometers). It’s deep. It's thick. It's where those massive "anvil" thunderstorms have room to grow into monsters.

📖 Related: What Was Invented By Benjamin Franklin: The Truth About His Weirdest Gadgets

But move toward the poles, and the whole thing sags.

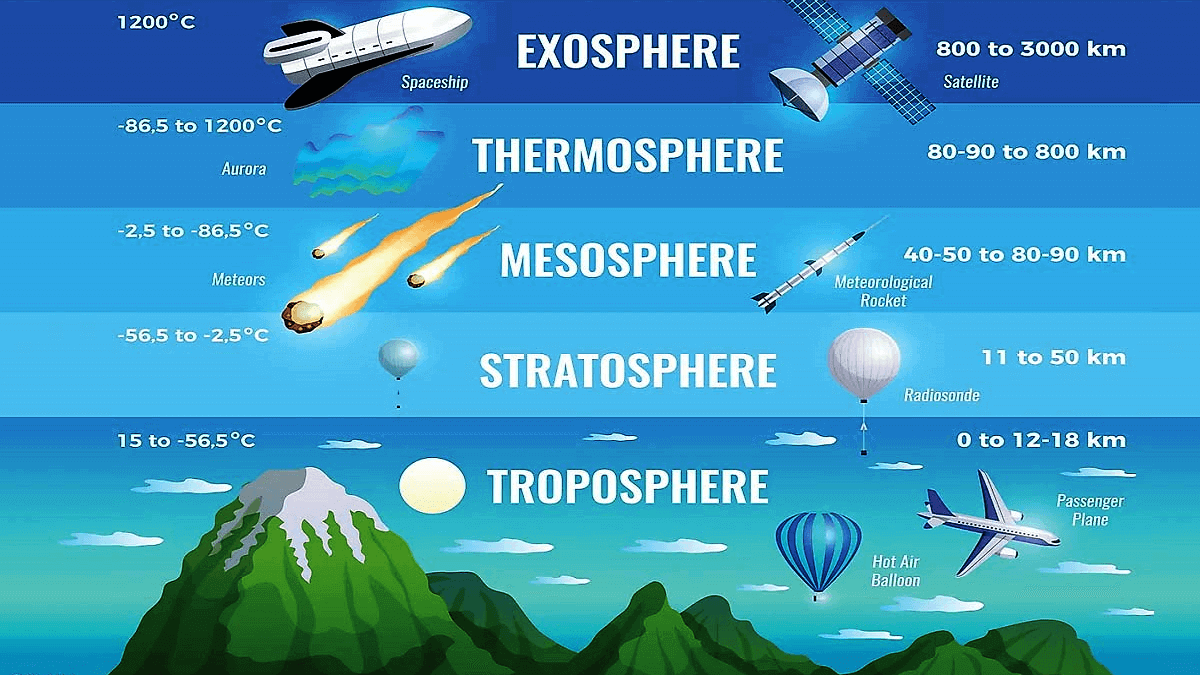

The air is colder, denser, and it just doesn't have the thermal energy to push upward. Near the North and South Poles, the troposphere might only be 4 or 5 miles high (around 7 to 8 kilometers). That is remarkably shallow. To put that in perspective, a commercial airliner flying at 35,000 feet would be cruising well above the troposphere at the poles, sitting comfortably in the stratosphere. Meanwhile, that same plane over the Amazon would still be deep within the "weather layer."

Seasonal Swell: The Atmosphere’s Summer Body

Temperature is everything here. Because warm air is less dense than cold air, the troposphere literally grows and shrinks with the seasons.

During the summer, the increased solar radiation heats the land and sea. This heat transfers to the air, causing it to expand. Consequently, the troposphere is higher in the summer than it is in the winter. It’s a rhythmic, annual pulse. If you were to watch a time-lapse of the Earth's atmosphere over a year, you’d see the troposphere bulging toward the sun-drenched hemisphere and retreating in the dark, frozen one.

👉 See also: When were iPhones invented and why the answer is actually complicated

NASA’s Earth Observatory and data from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory have tracked these shifts for decades. They’ve noted that as global temperatures rise, the troposphere is actually getting slightly thicker. It’s expanding. Researchers like Santer et al. have published work showing that the tropopause (that boundary layer) has been rising by about 50 to 60 meters per decade. It’s a subtle but definitive signature of a warming world.

Why Does the Height Actually Matter?

It’s not just a trivia question for pilots or meteorologists. The height of this layer dictates how our weather functions.

The troposphere contains roughly 75% to 80% of the atmosphere's total mass. More importantly, it holds almost all the water vapor. This is why "weather" as we know it—rain, snow, lightning, tornadoes—is trapped in this bottom layer. The tropopause acts like a lid. When a massive thunderhead grows, it hits that ceiling and starts spreading out horizontally because the air above it (in the stratosphere) is actually warmer, preventing the moist air from rising further.

The Composition Factor

Density drops off fast.

✨ Don't miss: Why Everyone Is Talking About the Gun Switch 3D Print and Why It Matters Now

- Bottom Heavy: Gravity pulls most air molecules down to the surface.

- Pressure: At the top of the troposphere, the air pressure is only about 10% of what it is at sea level.

- Oxygen: You can’t breathe up there. Not even close.

What Most People Get Wrong About the "Ceiling"

There is a common misconception that the atmosphere just "ends" at a certain point. It doesn't. It fades.

The tropopause is the transition zone where the temperature stops dropping as you go higher. In the troposphere, the rule is simple: higher equals colder. That’s why mountains have snow. But once you hit the tropopause, the temperature stabilizes and then actually starts to increase in the stratosphere because of the ozone layer absorbing UV radiation.

This thermal inversion is the real reason the troposphere has a "height" at all. It’s a temperature barrier, not a physical one. If you're a passenger on a long-haul flight, look out the window. If the clouds below you look like a flat, white carpet and the sky above is a dark, piercing blue, you’ve likely crossed that threshold. You’re looking down at the top of the troposphere.

Actionable Insights for Enthusiasts and Travelers

Knowing the height of the troposphere can actually change how you look at the world around you.

- Watch the Clouds: If you see "Altocumulus" clouds, you’re looking at moisture sitting roughly in the middle of the troposphere (about 6,500 to 20,000 feet). If you see wispy "Cirrus" clouds made of ice crystals, you’re looking at the very top of the layer.

- Flight Tracking: Next time you fly, check your altitude on the seatback screen. If you're over 36,000 feet in a temperate zone like the U.S. or Europe, you are likely skimming the very top or sitting just inside the stratosphere. Notice how the turbulence usually disappears? That’s because you’ve left the chaotic, convective air of the troposphere behind.

- Mountain Climbing: If you ever tackle a "fourteener" or higher, remember you are physically moving through a significant percentage of the troposphere's mass. The "thin air" isn't just a feeling; it's the result of being miles closer to the tropospheric ceiling.

The troposphere is our life support system. It’s thin, it’s fragile, and it’s surprisingly shallow compared to the size of the Earth. If the Earth were the size of an onion, the troposphere would be thinner than the very outermost skin. Understanding its height helps us understand the delicate balance required to keep our weather—and ourselves—functioning.

Monitor local meteorological balloon launches if you want to see real-time data. Sites like the University of Wyoming’s atmospheric science department provide sounding data that shows exactly where the tropopause sits over your head today. It’s never the same twice.