You’re standing on a rock. That rock is spinning at about 1,000 miles per hour, orbiting a giant ball of plasma, which is itself screaming through a vacuum at 500,000 miles per hour. When people ask how far is Milky Way from Earth, they usually expect a single number, like a mileage sign on a highway. But there's a problem. You’re already there.

It’s like asking a fish how far it is from the ocean.

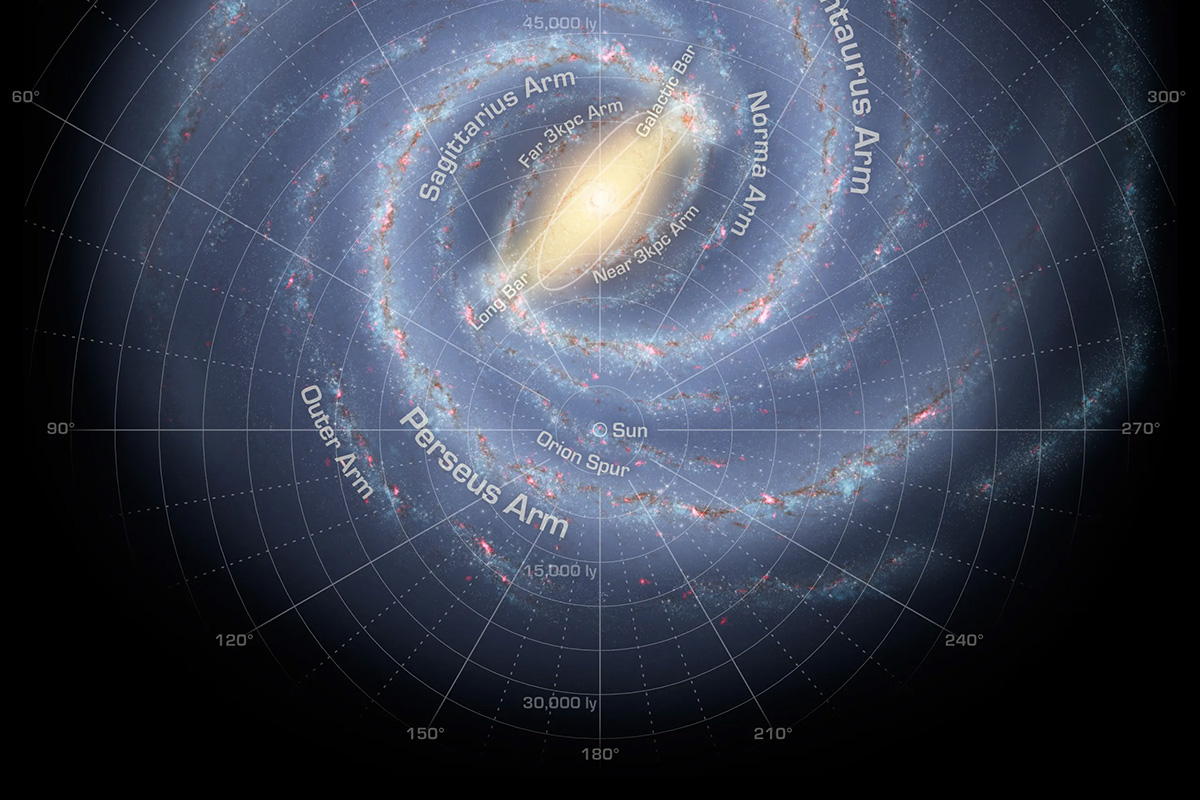

We aren't looking at the Milky Way from a distance; we are embedded in one of its spiral arms, about 26,000 light-years away from the chaotic, star-packed center. Imagine a massive, glowing pancake made of 100 billion to 400 billion stars. We’re sitting about halfway between the edge and the middle, tucked into a quiet suburban neighborhood called the Orion Arm.

The "How Far" Question is Actually a Geometry Problem

Most of the time, when you see that beautiful, hazy river of light in a dark sky, you're looking at the edge-on view of our own galaxy's disk. Because we're inside it, the "distance" depends entirely on which direction you point your telescope.

If you look "up" or "down" out of the galactic plane, the edge of the galaxy is actually quite close—only about 1,000 light-years away. That’s just a hop, skip, and a jump in cosmic terms. But if you look toward the center, toward the constellation Sagittarius, you’re looking across a vast gulf of 26,000 light-years of dust, gas, and ancient stars.

Space is mostly empty. That’s the first thing any astronomer like Dr. Becky Smethurst or the folks at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory will tell you. Even though there are billions of stars, the gaps between them are so hauntingly large that our brains aren't really wired to process the scale. One light-year is roughly 5.88 trillion miles. Multiply that by 26,000 to reach the center. The math gets stupidly large, very fast.

Why We Can't Just Take a Picture of It

Have you ever seen those "You Are Here" maps of the Milky Way? They’re lies. Well, not lies, but artistic guesses.

🔗 Read more: Who is my ISP? How to find out and why you actually need to know

We have never seen the Milky Way from the outside. Think about it. To get a camera far enough away to take a "top-down" photo of our galaxy, we would have to send a probe hundreds of thousands of light-years into the intergalactic void. The Voyager 1 spacecraft, the furthest human-made object, has been traveling since 1977 and hasn't even left our "backyard" solar neighborhood yet. It's barely 23 light-hours away.

Basically, we're trying to map a house while locked in a small closet.

We use radio waves and infrared light to "see" through the thick clouds of cosmic dust that block our view of the galactic center. This is how the Gaia mission from the European Space Agency is currently building the most precise 3D map of our galaxy ever made. By measuring the "parallax" (the slight shift in a star's position as Earth orbits the sun), we can pinpoint exactly how far is Milky Way from Earth in terms of its various landmarks and spiral structures.

Breaking Down the Neighborhood Distances

It helps to think of the galaxy as a city.

- The Solar System is your house.

- The Oort Cloud is your yard.

- The Alpha Centauri system (4.3 light-years away) is your neighbor’s house.

- The Galactic Center (26,000 light-years away) is the bustling downtown area you visit once a year.

- The Edge of the Disk (roughly 50,000 light-years away in the other direction) is the city limits.

We used to think the Milky Way was about 100,000 light-years across. Recent data suggests it might be wider, perhaps up to 150,000 or even 200,000 light-years, if you count the "dark matter halo" and the thin ripples of stars at the very edges.

The Monster in the Middle: Sagittarius A*

The reason we care about the distance to the center is because of what lives there. A supermassive black hole. It’s called Sagittarius A* (pronounced "A-star"), and it has the mass of 4 million suns.

💡 You might also like: Why the CH 46E Sea Knight Helicopter Refused to Quit

Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2020 for proving this thing exists. They spent decades tracking the orbits of stars near the center of the galaxy. They watched these giant stars whip around "nothing" at incredible speeds. The only thing that could make a star move that fast is a gravity well so deep and so dense that it could only be a black hole.

Even though it’s 26,000 light-years away, its gravity keeps the entire "city" of the Milky Way organized. We are effectively in a long-term orbit around this invisible titan. Don't worry, though; we aren't getting sucked in. We're moving fast enough to stay in a stable, circular path, much like Earth stays in orbit around the Sun without falling into the fire.

Measuring the Void: How Scientists Actually Do This

How do we know any of this? We use "standard candles."

Imagine you see a candle in a dark field. You know how bright a candle should be. If it looks very dim, it’s far away. If it’s bright, it’s close. Astronomers use specific types of stars—Cepheid variables and RR Lyrae stars—that pulse with a predictable rhythm. The speed of the pulse tells us the star's actual brightness. By comparing that "true" brightness to how dim it looks from Earth, we can calculate the distance with incredible accuracy.

Recently, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) gave us the first actual image of Sagittarius A*. It looked like a blurry orange donut. That "donut" is the light from gas being shredded as it nears the event horizon. Seeing that image confirmed our distance measurements better than almost anything else. We are exactly where we thought we were: in the suburbs, far from the chaos, which is probably why life was able to evolve here in the first place.

The Future of the Milky Way (Spoiler: It's a Collision)

The Milky Way isn't a static object. It's moving. And it's on a collision course.

📖 Related: What Does Geodesic Mean? The Math Behind Straight Lines on a Curvy Planet

The Andromeda Galaxy (M31) is currently about 2.5 million light-years away. That sounds like a lot, but it's screaming toward us at 250,000 miles per hour. In about 4 billion years, the Milky Way and Andromeda will begin a gravitational dance, eventually merging into one giant elliptical galaxy often nicknamed "Milkomeda."

Because space is so empty, the stars themselves likely won't hit each other. It’ll just be a massive reorganization of the neighborhood. The "how far" question will change completely as the sky fills with the light of a trillion new neighbors.

Real-World Action Steps for Stargazers

If you want to experience the scale of the Milky Way yourself, you can't do it from a city. Light pollution kills the view. Here is how you actually "see" the distance:

- Find a Dark Sky Park: Use a tool like the International Dark-Sky Association map. You need a "Bortle Class 1 or 2" sky to see the galactic core clearly.

- Timing is Everything: In the Northern Hemisphere, "Galaxy Season" is summer. Look south in July and August. You’re looking directly toward the center of the galaxy.

- Use Binoculars, Not a Telescope: A telescope zooms in too much. A simple pair of 10x50 binoculars will reveal thousands of stars, nebulae, and star clusters that are tens of thousands of light-years away.

- Identify the "Teapot": Look for the constellation Sagittarius. It looks like a teapot. The "steam" coming out of the spout is actually the densest part of the Milky Way—the light from millions of stars 26,000 light-years away.

- Download a Tracker: Use apps like Stellarium or SkyGuide. They use your phone's GPS to show you exactly where the galactic plane is, even during the day.

Knowing the distance to the Milky Way's landmarks transforms the night sky from a flat wallpaper into a deep, 3D ocean. We are passengers on a massive, spiraling ship, and we’re just now beginning to understand the layout of the decks.

The most important takeaway? You are part of the galaxy. You aren't just looking at it; you’re made of it. Every atom of carbon in your body was cooked inside a star that lived and died somewhere in those 100,000 light-years of space. When you look at the Milky Way, you’re basically looking in a mirror.