Ever stared at a doodle on a napkin and felt a weirdly specific pang of sadness? Or maybe you’ve looked at a single panel in a graphic novel and felt like you just read a hundred pages of backstory. That’s the magic. Honestly, drawings that tell a story aren't just about being a "good artist" in the technical sense. It’s about visual shorthand. It’s about how our brains are wired to find a narrative in literally anything, even three lines and a circle.

Humans have been doing this forever. Think Lascaux cave paintings. Those weren't just "decorations" for the stone-age living room. They were hunting guides, religious tallies, and historical records. They were the original storyboard.

The Mechanics of Narrative Art

If you want to understand how a static image moves a plot forward, you have to look at "The Gaze." It’s a term art historians like E.H. Gombrich talked about a lot. Basically, your eye follows a path. A smart artist places "visual anchors" to lead you through the timeline of the drawing.

One image. One moment. But somehow, it implies a "before" and an "after."

Take Norman Rockwell. People call his stuff kitschy now, but the man was a genius at narrative compression. Look at The Runaway. You see a little boy on a barstool next to a massive police officer. You don't need a caption. The knapsack on the floor tells you he’s leaving home. The officer’s kind expression tells you he’s going back. The timeline is baked into the props.

Why Detail Usually Kills the Vibe

A common mistake? Putting in too much.

💡 You might also like: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

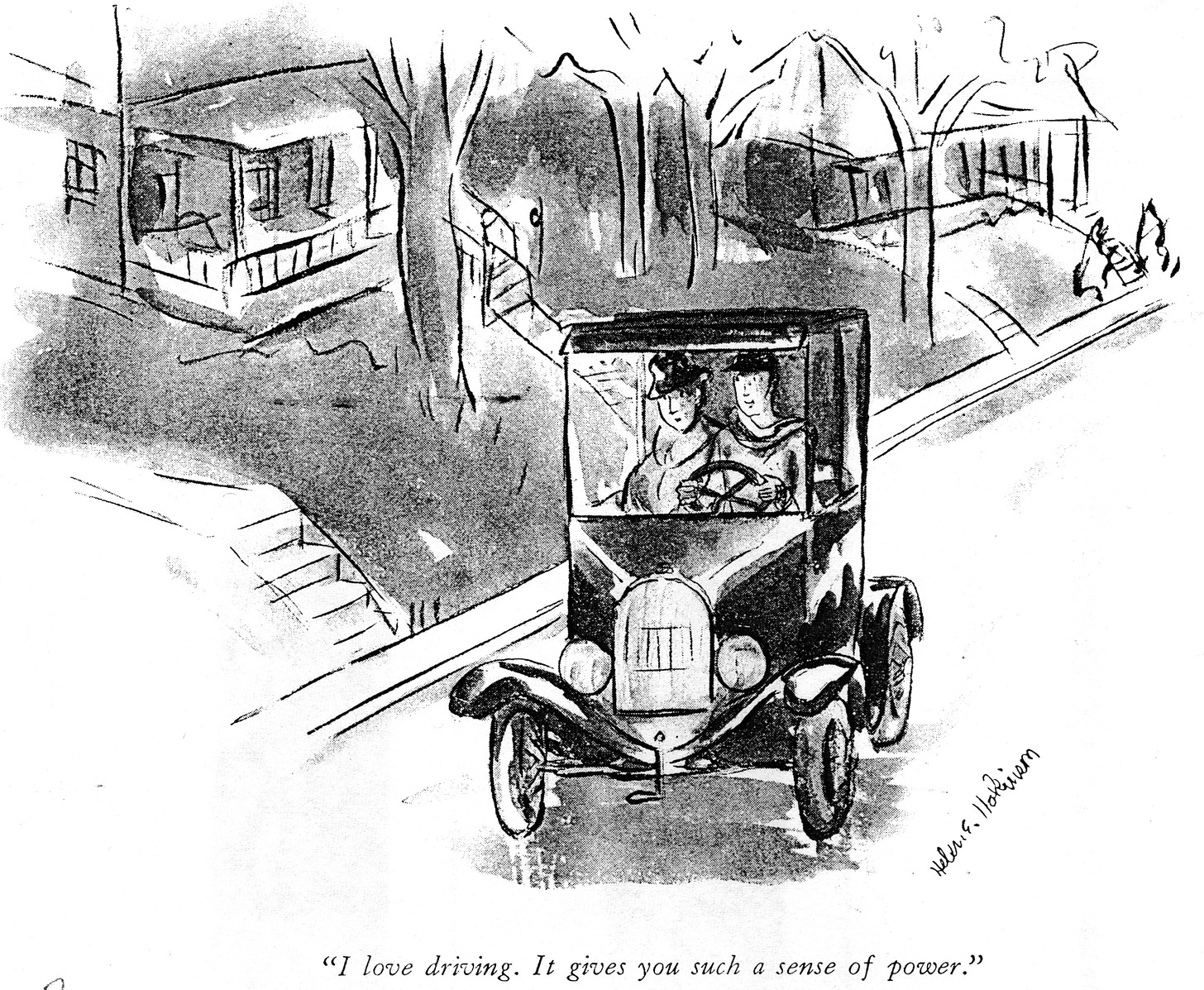

Scott McCloud, in his seminal book Understanding Comics, explains the "Big Daddy" concept of icons. The more a face looks like a specific person, the less we relate to it as "ourselves." But a smiley face? Everyone sees themselves in a smiley face. When you’re creating drawings that tell a story, leaving gaps is actually a favor to the viewer. It lets them fill in the blanks with their own baggage.

Real-World Examples of Storytelling Without Words

You’ve probably seen those "Long Dog" or "Slightly Wrong" illustrations floating around social media. They work because they lean into absurdity. But let's look at something more formal.

Shaun Tan’s The Arrival is a masterpiece of this. It’s a 128-page book with zero words. None. It uses a sepia-toned, surrealist style to explain the immigrant experience. Because there's no text, the viewer feels as lost as the protagonist in a new land. The "story" is told through the texture of the paper and the frantic pace of the panel layouts.

Then there’s the political cartooning world. Think of someone like Herblock or Bill Mauldin. During WWII, Mauldin’s "Willie and Joe" characters told the story of the weary infantryman better than any news dispatch ever could. One drawing of two tired guys in a foxhole communicated the exhaustion of an entire generation.

How to Actually Build a Narrative in Your Art

Stop trying to draw a "scene" and start trying to draw a "consequence."

📖 Related: Bondage and Being Tied Up: A Realistic Look at Safety, Psychology, and Why People Do It

If you draw a glass falling off a table, that’s an action. If you draw the shattered glass on the floor and a cat looking suspiciously innocent in the corner, that’s a story. The story exists in the space between the cause and the effect.

- The Power of Props: A discarded wedding ring on a nightstand says more than a three-page breakup letter.

- Lighting as Mood: High-contrast "Chiaroscuro" (think Caravaggio) creates drama and tension.

- Body Language: A slumped shoulder or a clenched fist provides the "internal monologue" of the character.

Honestly, some of the best drawings that tell a story are the ones that make you ask questions rather than giving you answers. Why is that door cracked open? Why is the character wearing one shoe?

The "Golden Minute" Rule

Concept artists in the film industry often talk about the "Golden Minute." This is the idea that a viewer should be able to look at a piece of concept art and, within sixty seconds, understand the stakes of the entire movie. If you’re drawing a dragon, don't just draw a dragon. Draw a dragon sleeping on a pile of rusted knight helmets. Now we know the dragon wins. We know the knights failed. We know the world is dangerous.

Common Misconceptions About Visual Storytelling

A lot of people think you need to be a master of anatomy to tell a story. Not true. Look at Hyperbole and a Half by Allie Brosh. Her drawings are intentionally "bad" in a traditional sense—crude, MS Paint-style figures. Yet, her stories about depression and her dogs are some of the most poignant, viral narrative art of the last twenty years. The "story" is in the timing and the expression, not the muscle structure.

Another myth? That every drawing needs a "twist."

Sometimes the story is just a vibe. A quiet afternoon. The way sunlight hits a dusty floor. Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks doesn't have a "plot" in the traditional sense. Nothing is happening. But the story of urban loneliness is so loud you can practically hear the hum of the fluorescent lights.

👉 See also: Blue Tabby Maine Coon: What Most People Get Wrong About This Striking Coat

Practical Steps to Improve Your Visual Narrative

If you’re looking to get better at this, or just appreciate it more, try these specific exercises.

- The Three-Object Challenge: Draw three unrelated objects (like a key, a melted ice cream cone, and a birdcage) and try to arrange them so they imply a specific event happened.

- Crop for Drama: Take a photo or a drawing and crop it tightly. Often, what you don't see makes the story more compelling. A hand reaching for a door handle is more tense than a full shot of a person walking toward a house.

- Study Silent Film: Watch old Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin shorts. They couldn't rely on dialogue, so every movement and every "set" drawing had to communicate intent.

- Change the Weather: If your story feels flat, change the environment. A birthday party in the rain tells a very different story than a birthday party in the sun.

Drawings that tell a story aren't about technical perfection; they’re about emotional resonance. You don't need a degree from CalArts to understand that a drawing of a child holding a wilted flower is a story about disappointment. You just need to be human.

Next time you pick up a pencil or browse an art gallery, look for the "ghosts" in the image. Look for what happened five minutes before the artist "froze" the frame. That’s where the real narrative lives.

Actionable Insights for Narrators

- Focus on the "Aftermath": Instead of drawing the climax, draw the quiet moment immediately following it. This forces the viewer to reconstruct the action in their head, making them an active participant in the story.

- Use Color Cues: Warm colors for safety, cool colors for isolation. It’s a trope because it works on a primal level.

- Simplify the Subject: If the background is the story, make the character a silhouette. If the character is the story, blur the background.

The most effective visual stories are the ones that trust the audience to be smart enough to get the point without a label. Keep your drawings lean, keep your symbols clear, and let the viewer's imagination do the heavy lifting.