You probably haven't thought about your scanner in months. It sits there, a dusty plastic slab in the corner of the office, or maybe it’s integrated into that bulky "all-in-one" printer that jams every time you’re in a hurry. But then, you suddenly need to digitize a signed contract or archive a box of fading polaroids from 1994. That’s when the magic—and the frustration—begins. We take it for granted, but the process of turning physical atoms into digital bits is a feat of engineering that involves high-end optics, precise mechanical timing, and a whole lot of light.

Basically, a scanner is a bridge. It’s a translator. It takes the analog world (paper, ink, texture) and converts it into a language your computer understands: binary.

The Inner Workings: How Does a Scanner Work?

If you crack open a standard flatbed scanner—which I don't recommend if you want it to keep working—you’ll see a surprisingly simple layout. It’s mostly empty space, a glass pane (the platen), and a moving carriage. This carriage is the heart of the machine.

🔗 Read more: Is Santa Tracker Real? What’s Actually Happening Behind the Scenes

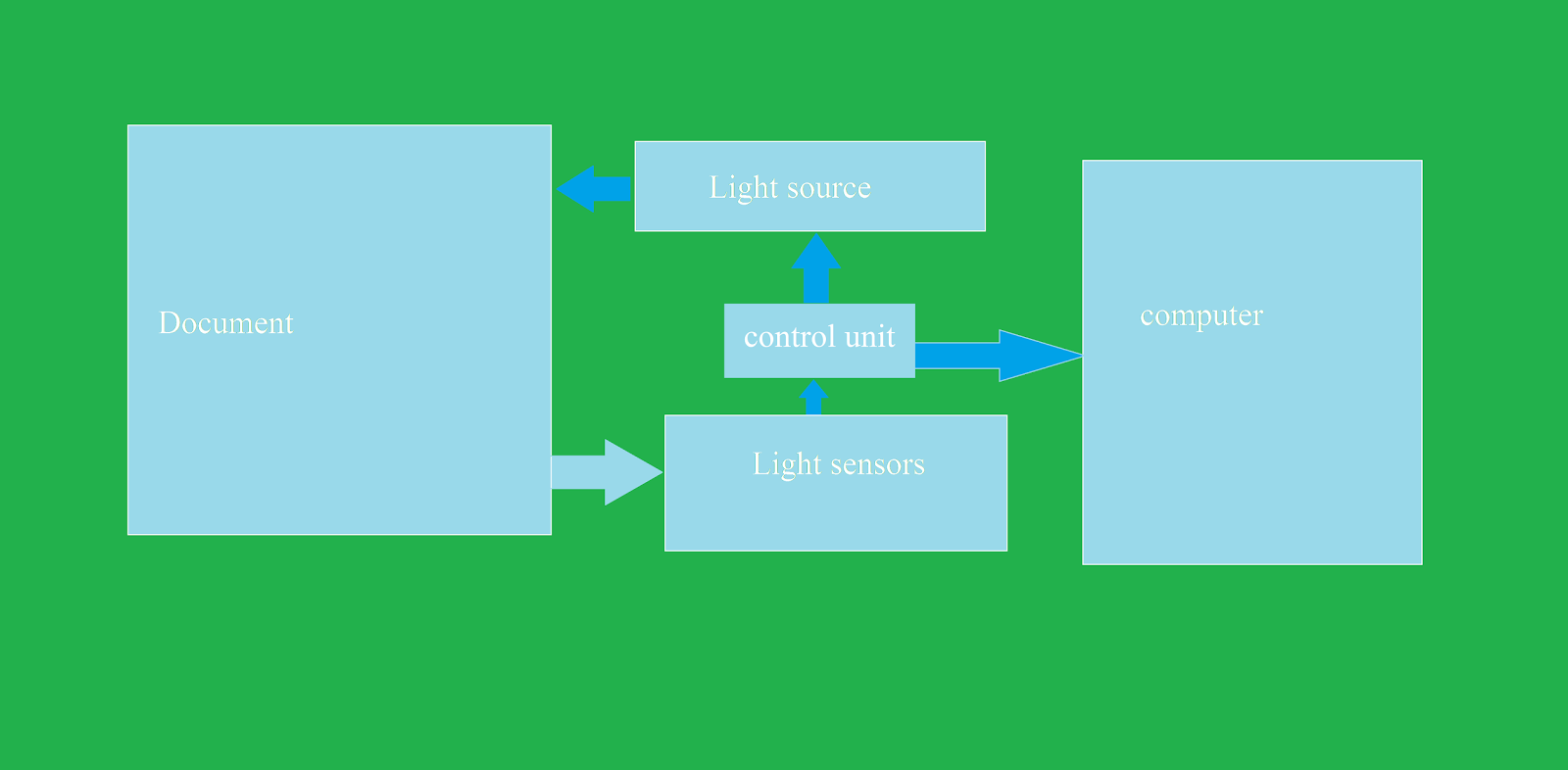

When you hit "scan," a few things happen simultaneously. First, a bright light source illuminates the document. In older models, this was a Cold Cathode Fluorescent Lamp (CCFL). If you’ve ever noticed an old scanner takes a minute to "warm up," that’s the lamp literally heating up to reach full brightness. Modern scanners usually use LEDs. They’re instant, they’re energy-efficient, and they don't hum like a haunted refrigerator.

As the light hits the paper, it bounces back. White paper reflects a lot of light. Black ink absorbs it. Colorful photos reflect specific wavelengths. This reflected light is captured by a series of mirrors and lenses that angle it toward a specialized sensor. This is where the real science happens.

The Sensor: CCD vs. CIS

Most people don't realize there are two main types of "eyes" a scanner can have.

Charged-Coupled Device (CCD) technology is the gold standard. It’s the same tech found in high-end digital cameras. CCD scanners use a real lens to focus the image onto the sensor. Because of this, they have a "depth of field." If you try to scan a bulky book and the spine doesn't touch the glass perfectly, a CCD scanner can still keep it in focus. They are bulky, expensive, and produce incredible detail.

On the flip side, we have Contact Image Sensor (CIS) technology. This is what’s inside those super-slim scanners and most office "all-in-ones." Instead of a complex system of mirrors and lenses, the sensors are placed almost directly against the glass. It’s cheaper. It’s thinner. But if your document isn't perfectly flat against the glass? It’ll be a blurry mess. Honestly, for standard documents, CIS is fine. For your grandmother's wedding photos? You want a CCD.

What Does It Do Beyond Just Making Copies?

We often think of scanners as "digital photocopiers," but that's a narrow view. Their utility spans across industries you might not expect.

In the medical field, scanners (albeit much more complex ones like CT or MRI machines) use similar principles of data acquisition to create 3D models of the human body. In the world of art preservation, ultra-high-resolution wide-format scanners allow museums to capture every microscopic crack in an oil painting, ensuring a digital record exists if the original ever degrades.

For the average person, a scanner is a tool for Optical Character Recognition (OCR). This is the coolest part of what a scanner does. It’s one thing to have a "picture" of a document. It’s another thing entirely for your computer to understand that the black squiggles on the screen are actually the letters "T-H-E."

🔗 Read more: Trump AI Video Pooping: What Really Happened with that Viral Clip

Software like Adobe Acrobat or ABBYY FineReader analyzes the scanned image, looks for patterns that match alphabet characters, and converts that image into a searchable, editable text file. It’s the difference between a dead image and a living document.

The Resolution Myth: DPI and Why It Matters

You’ll see numbers like "4800 x 9600 DPI" plastered on scanner boxes. DPI stands for Dots Per Inch.

Here’s the truth: for 90% of what you do, those massive numbers are marketing fluff. If you are scanning a standard letter to email to your lawyer, 300 DPI is plenty. If you are scanning a 4x6 photo to print it as a poster, then yes, crank it up to 600 or 1200 DPI.

Scanning at 4800 DPI creates files so massive they’ll crash your email and eat your hard drive for breakfast. More isn't always better; it’s just more. Optical resolution is the physical limit of the hardware. "Interpolated" resolution is just the software "guessing" what pixels should be there—it’s basically a digital lie. Ignore interpolation numbers. Look for the optical specs.

Why Your Scanner Might Be Flickering or Streaking

Nothing is more annoying than a giant vertical line running through your scan. Usually, this isn't a broken sensor. It’s dust.

Because scanners rely on such precise paths of light, even a tiny speck of dust on the calibration strip (usually a white bar at the very end of the glass) can trick the sensor into thinking there's a permanent line of that color across the whole page. A quick wipe with a microfiber cloth and some glass cleaner—applied to the cloth, never the glass directly!—fixes this nearly every time.

Scanners are also incredibly sensitive to "noise." If your power supply is unstable or your USB cable is shielded poorly, you might get grainy artifacts in the dark areas of your images. It’s a delicate balance of electricity and light.

✨ Don't miss: Weather Radar Joplin MO: What Most People Get Wrong About Tracking Storms

Actionable Steps for Better Scans

If you want to move beyond basic "hit the green button" scanning, keep these three tips in mind:

- Check your glass: Even if it looks clean, skin oils from your fingers can create "fog" that softens the image. Clean it before any high-quality photo project.

- The "Straight Edge" Trick: Don't rely on the plastic borders of the scanner to get your document straight. They are often slightly misaligned. Scan a bit wider than you need and use software to crop and rotate.

- Bit Depth Matters for Photos: If your scanner settings allow you to choose between 24-bit and 48-bit color, choose 48-bit for photos you plan to edit. It captures significantly more data in the shadows and highlights, giving you more "room" to fix colors in Photoshop later without the image falling apart.

Scanners aren't obsolete. In an era of "phone-scanners," a dedicated flatbed still offers superior lighting, better focus, and zero perspective distortion. Whether you're digitizing tax returns or preserving family history, understanding the dance between the light, the motor, and the sensor makes the whole process feel a lot less like a chore and a lot more like a technical marvel.

For the best results, always preview your scan first. It saves time, saves storage, and ensures that the one time you actually need that scanner, it does exactly what it was designed to do: bridge the gap between your physical life and your digital world.