It feels like a magic trick. You take a coil of wire, a tiny rock, and some headphones, and suddenly, voices from hundreds of miles away start whispering in your ear. There is no plug. No AA batteries. No lithium-ion cells. If you’ve ever wondered how does a crystal radio work, the answer is honestly a bit mind-bending: the radio is powered entirely by the invisible energy of the radio waves themselves.

That’s right. The signal is the power source.

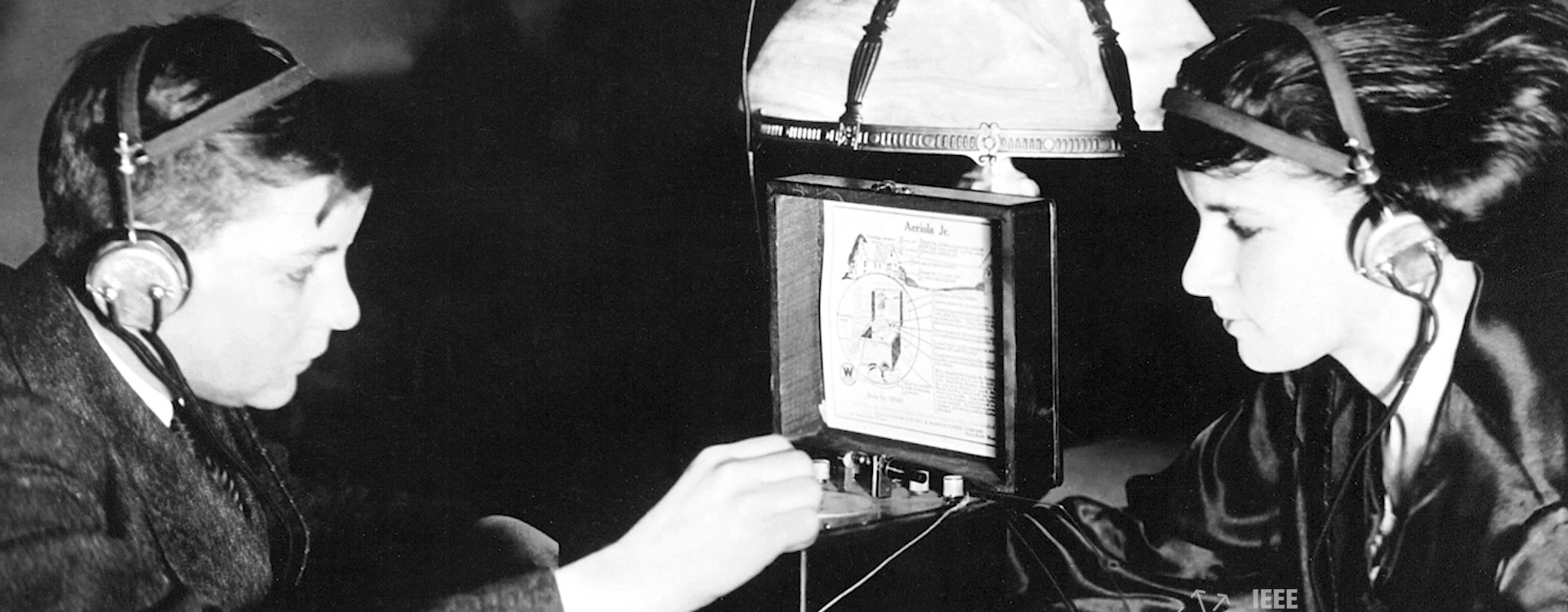

Most of us are so used to our smartphones and Bluetooth speakers that we forget air is thick with electromagnetic energy. A crystal radio is just a simple machine designed to harvest that energy. It’s the ultimate survivalist tech, a favorite of Boy Scouts for a century, and honestly, one of the most elegant pieces of engineering ever conceived. But it isn't just about "magic rocks." It’s about resonance, rectification, and the physics of the electromagnetic spectrum.

The Mystery of the "Powerless" Radio

You've probably heard that energy cannot be created or destroyed. In a standard modern radio, we use a battery to amplify a weak signal so it's loud enough for a speaker. A crystal set doesn't do that. Because there is no amplification, the sound you hear is solely the result of the energy captured by your antenna.

This is why your antenna needs to be long. Like, really long. We’re talking 20 to 50 feet of copper wire strung up in a tree or across a roof. The longer the wire, the more "surface area" you have to catch those passing radio waves. These waves induce a tiny, microscopic alternating current (AC) in the wire.

But you can't just hook a long wire to a speaker and expect to hear Taylor Swift. If you did that, you’d just hear a mess of every radio station in the city overlapping into a hum of white noise. You need a way to pick one station and ignore the rest.

Tuning into the Frequency: The LC Circuit

Think of a crystal radio like a swing on a playground. If you push the swing at the wrong time, nothing happens. But if you push it at exactly the right rhythm—the resonant frequency—the swing goes higher and higher with very little effort.

In electronics, we do this with an "LC circuit." The L stands for an inductor (a coil of wire) and the C stands for a capacitor.

When you wind wire around a tube to make a coil, it resists changes in current. When you pair it with a capacitor (which stores an electric charge), the two components start playing a game of "electrical catch." The energy bounces back and forth between them at a very specific speed. By sliding a brass contact across the coil or turning a knob on a variable capacitor, you change that speed.

When the "speed" of your circuit matches the frequency of a broadcast station, the circuit vibrates in sympathy. This is resonance. It filters out the noise and lets only one signal through.

The Secret Ingredient: That Weird Little Crystal

This is where the name comes from. In the early 1900s, hobbyists used a literal piece of crystalline mineral—usually galena (lead sulfide). They would use a fine, pointy wire called a "cat's whisker" to poke the crystal until they found a sensitive spot.

Why? Because radio waves are high-frequency AC. They flip back and forth millions of times per second. Your ears can’t hear that, and your headphones can’t move that fast. If you sent that raw AC signal to your headphones, the diaphragm wouldn't move at all because it’s being pulled back and forth so quickly it just stays still.

The crystal acts as a diode.

A diode is a one-way valve for electricity. It chops off half of the radio wave, turning it from alternating current into a series of pulses that move in only one direction. This process is called rectification. Once the signal is "rectified," the high-frequency carrier wave can be filtered out, leaving behind the "envelope"—the actual audio signal representing the human voice or music.

Modern builders usually swap the galena crystal for a germanium diode (like the 1N34A). It’s way more reliable than poking a rock with a needle for twenty minutes, but the physics remains identical.

Why You Need High-Impedance Headphones

Here is where most people fail when building their first set. You cannot use the earbuds that came with your old iPhone.

Standard modern headphones have "low impedance" (usually 16 or 32 ohms). They require a decent amount of current to move the tiny speakers inside. A crystal radio produces almost zero current. If you plug in modern earbuds, the tiny signal from the antenna will simply vanish into the ground without making a peep.

You need high-impedance headphones, usually ceramic or "crystal" earphones, which have an impedance of 20,000 ohms or more. These are incredibly sensitive. They can turn the tiniest whisper of electricity into a sound you can actually hear.

👉 See also: How to make a copy of a Word doc without ruining your formatting

The Limitations of Physics

It isn't all sunshine and free music. Because there's no battery, the volume is incredibly low. You won't be "rocking out." It's more like a ghost whispering in your ear.

Distance is also a huge factor. You’re limited by the power of the transmitter. AM stations (Amplitude Modulation) are the only ones you’ll catch because FM (Frequency Modulation) requires much more complex circuitry to decode. If you live 50 miles from a 50,000-watt AM transmitter, you’ll hear it loud and clear. If you’re in a remote valley, you might hear nothing but static.

Also, ground is everything. To make the circuit work, you need a "return path" for the electricity. Most builders clip a wire to a cold-water pipe or a metal stake driven into the dirt. Without a solid ground, the electrons have nowhere to go, and the radio stays silent.

Real-World History: The Foxhole Radio

Understanding how does a crystal radio work isn't just a science fair project; it was a survival skill. During World War II, soldiers in the field didn't always have access to batteries or vacuum tubes. They built "foxhole radios."

Instead of a galena crystal, they used a rusty razor blade and a pencil lead. The layer of rust (iron oxide) on the blade acted as a crude semiconductor. By touching the pencil lead to different spots on the rusty blade, they could rectify the signal. It allowed them to listen to news and music behind enemy lines without a power source that could be tracked or run out of juice.

What Most People Get Wrong

A common misconception is that the radio "creates" sound. It doesn't. It's more accurate to say the radio is a translator. It takes the kinetic energy of electrons vibrating in the air and converts them into the physical vibration of a thin piece of plastic in your ear.

Another myth is that you can "boost" a crystal radio by adding more coils. While more coils might help with tuning, they don't add power. You are always limited by the energy hitting your antenna. If you want it louder, get a longer wire or move closer to the radio station's tower.

Why This Tech Still Matters in 2026

In an era of 5G, satellite internet, and complex microchips, the crystal radio is a reminder of the fundamental laws of nature. It’s a "zero-point" technology. If the power grid goes down and the internet disappears, the AM airwaves will likely still be there, and a crystal radio will still be the only device that works without a charger.

✨ Don't miss: Why Google Assistant Keeps Popping Up and How to Finally Make it Stop

It teaches us about the "invisible world." We are surrounded by data at all times. A crystal radio is the simplest possible interface between that data and our human senses.

Actionable Steps for Building or Testing a Crystal Radio

If you want to experience this firsthand, don't just read about it. The physics clicks much faster when you’re actually hunting for a signal in the dark.

- Source a Germanium Diode: Look for a 1N34A diode online. Don't use a standard silicon diode (like a 1N4148); they require too much voltage to "turn on," and your radio signal won't be strong enough to crack them open.

- The Antenna is Everything: Aim for at least 30 feet of 22-gauge copper wire. Keep it as high as possible and away from power lines (for safety and to reduce hum).

- Find a High-Impedance Earpiece: You can find these at electronics hobby shops. If you must use modern headphones, you'll need a "matching transformer" (like a small 1k to 8-ohm audio transformer) to step down the impedance.

- Scuff Your Ground: If you're using a water pipe for your ground connection, make sure you sand off any paint or corrosion. You need a clean metal-to-metal contact to let those electrons flow freely.

- Patience is a Virtue: Tuning a crystal radio is fiddly. Move your tuner in tiny increments. At night, the AM band "skips" off the ionosphere, meaning you might suddenly pick up a station from three states away that wasn't there during the day.

The magic of the crystal radio isn't just that it works; it’s that it works for free, forever, using nothing but the air around you. It's a quiet, persistent reminder that the universe is full of energy, just waiting for us to tune in.