You’re sitting in a dimly lit izakaya in Shinjuku. The steam from the yakitori is rising. You look across the table and realize it’s time. You want to say it. But then you freeze. If you try to figure out how do you say love in japan, you'll quickly realize that a simple dictionary search is a trap.

Language isn't just words. It’s a cultural minefield.

In English, we throw "love" around like confetti. We love pizza. We love our moms. We love that new Netflix show. We love our partners. Japanese doesn't work that way. It's a high-context language where what you don't say often carries more weight than what you do. If you walk up to someone you've been dating for three weeks and drop an "Ai shiteru," you might as well be proposing marriage while holding a blood oath. It’s heavy. It’s intense. And honestly, it’s probably not what you actually mean.

The Suki Spectrum: More Than Just "Like"

Most people start with Suki (好き).

If you’ve watched even five minutes of anime, you’ve heard this. "Suki desu." It’s usually translated as "I like you." But in the context of a confession—the famous kokuhaku culture—it basically means "I have feelings for you." It’s the entry point. It’s safe but significant.

Then there is Daisuki (大好き). Adding the kanji for "big" (大) turns "like" into "really like." For many Japanese couples, this is the ceiling. They might go their entire lives only ever saying daisuki. It’s warm. It’s comfortable. It covers everything from "I love this ramen" to "I want to spend my life with you."

The nuance is in the atmosphere, or kuuki wo yomu (reading the air). If you say "Daisuki" while holding someone's hand and looking into their eyes, they aren't thinking about ramen. They know exactly what you mean.

The Heavy Weight of Ai Shiteru

Now we get to the big one. Ai shiteru (愛してる).

✨ Don't miss: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

This is the one you see in movies. It's the one in the J-Pop ballads. But in real life? It's rare. Japanese culture historically values sasshi—the ability to understand someone’s feelings without them being spelled out.

I remember talking to a linguist in Kyoto who explained that Ai (愛) was actually a somewhat foreign concept when Western literature first started being translated into Japanese during the Meiji Restoration. Before that, the terms used were more about "longing" or "yearning" (koi). Ai felt academic. It felt heavy.

Today, Ai shiteru is reserved for the most profound, soul-binding moments. Think: deathbeds, wedding vows, or maybe a very dramatic goodbye at an airport. If you say it casually, it feels performative. It feels like you’re trying to act out a scene from a Hollywood movie. It’s "Western" in its directness. For many Japanese people, the sheer weight of the word makes it uncomfortable to say and equally uncomfortable to hear in a casual setting.

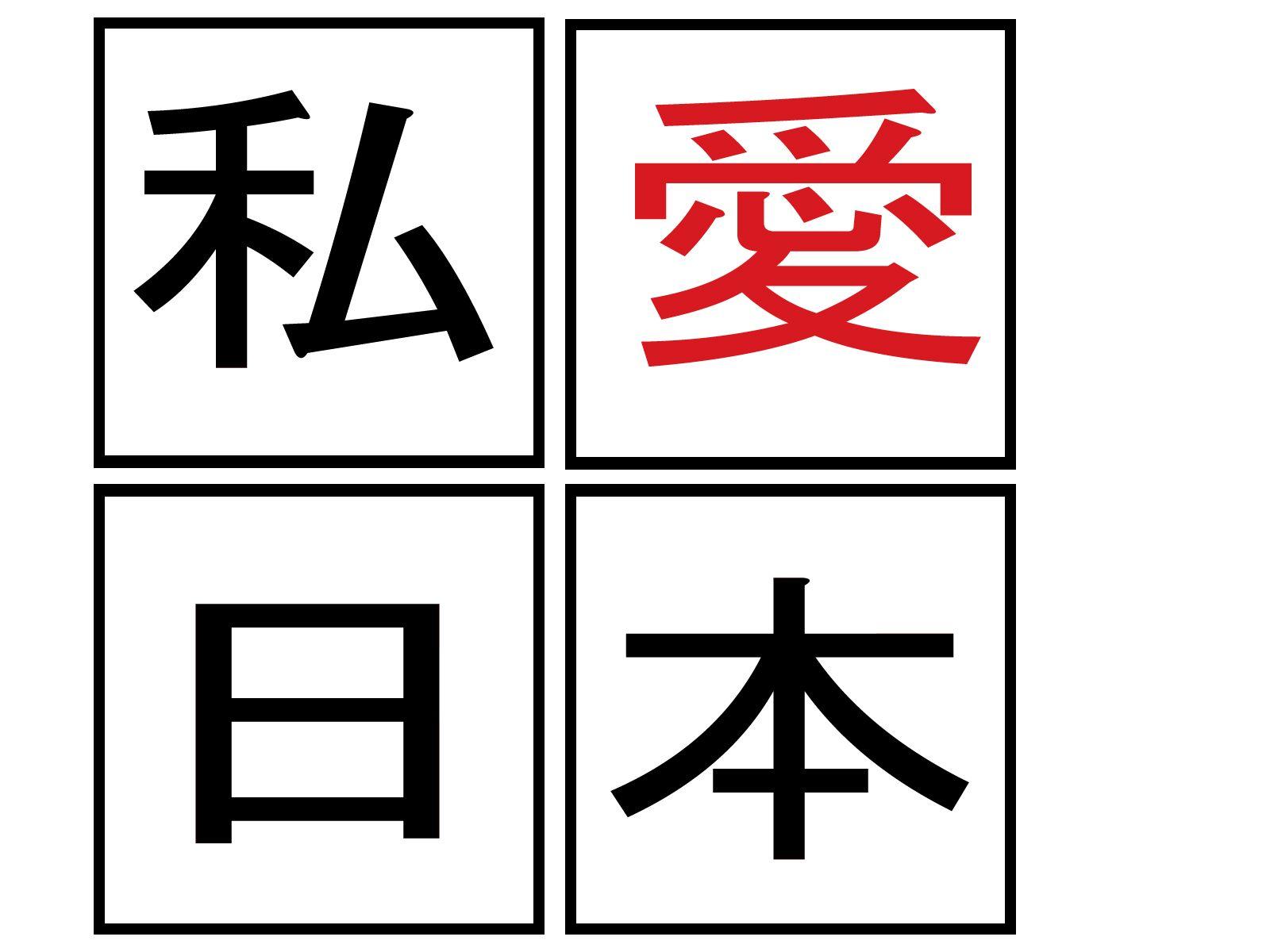

Koi vs. Ai: The Selfish vs. The Selfless

Japanese distinguishes between types of love in a way English doesn't quite capture.

- Koi (恋): This is romantic love. It’s the butterflies. It’s the "crush." It’s often described as somewhat selfish because it’s about your desire for the other person. You want them. You need them. The kanji for koi even contains the radical for "heart" (心) at the bottom, but traditionally, it's a heart that is "empty" or waiting to be filled.

- Ai (愛): This is the more mature, giving love. It’s selfless. It’s the kind of love that cares for another person’s well-being above your own. The kanji for Ai has the "heart" right in the middle, protected and centered.

When people ask how do you say love in japan, they are usually looking for Ren-ai (恋愛), which combines both characters. It’s the transition from the excitement of the crush (koi) to the stability of a long-term bond (ai).

Why Silence is the Ultimate Love Language

There is a famous, possibly apocryphal story about the novelist Natsume Soseki.

Supposedly, while he was teaching English, he told his students that "I love you" shouldn't be translated literally. A Japanese man, he argued, would never say something so blunt. Instead, he suggested translating it as: "Tsuki ga kirei desu ne" (The moon is beautiful, isn't it?).

🔗 Read more: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

The idea is that if two people are standing together, enjoying a beautiful moment in silence, and one points out the moon, they are acknowledging a shared soul. It’s the ultimate "if you know, you know" move. While modern Japanese people don't literally walk around saying "the moon is beautiful" to confess their love (unless they are being very nerdy or poetic), the sentiment remains.

Love is shown through omoiyari (consideration).

It’s your partner buying your favorite snack on the way home because they knew you had a bad day. It’s them making sure your umbrella is positioned so you don't get wet, even if their own shoulder gets soaked. In Japan, these actions don't just speak louder than words—they replace the words.

Regional Variations: Not Everyone is From Tokyo

If you’re in Osaka, things get a bit more colorful. The Kansai dialect (Kansai-ben) is known for being louder, funnier, and a bit more "down to earth."

An Osakan might say Suki ya nen.

It’s essentially the same as Suki da, but the "ya nen" ending adds a layer of warmth and colloquial grit. It’s the kind of thing you’d see on a hoodie or a souvenir keychain. It feels less like a stiff confession and more like a heartfelt, honest outburst.

The Social Media Shift

We have to talk about the 2026 reality of Gen Z in Tokyo. Things are changing.

💡 You might also like: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

Globalism and social media have made directness a bit more trendy. You’ll see "I love you" written in English in Instagram captions. You’ll hear younger couples using Ai shiteru more ironically or playfully. But even then, there is a lingering cultural "brake" that prevents it from becoming as common as it is in the West.

There’s a specific term called Amai or Amae—the desire to be pampered or to depend on another's indulgence. In a Japanese relationship, being able to show your "weak" side through amae is often a much bigger indicator of love than any three-word phrase.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Don't use Aishiteru on a first date. Seriously. Just don't. You’ll look like a stalker or someone who has learned everything they know about Japan from 90s romance manga.

Also, be careful with your particles.

- Anata ga suki (I like/love you).

- Anata wa suki (As for you, I like you... implying maybe I don't like others, or creating a weird contrast).

Actually, most of the time, Japanese people drop the "I" (watashi) and the "You" (anata) entirely. If you're looking at the person, they know who you're talking about. "Suki desu" is enough. Adding "I" and "You" makes it sound like a translated textbook sentence. It lacks the natural flow of real conversation.

Practical Steps for Expressing Love in Japan

If you are actually in a relationship with a Japanese person and want to navigate this properly, forget the dictionary for a second. Look at the context of your relationship.

- The Beginning: Stick with Suki or Suki desu. It’s honest. It’s the standard "confession" format.

- The Comfort Zone: Use Daisuki. It’s versatile. You can say it while laughing, while hugging, or while eating dinner. It builds intimacy without the "finality" of Ai shiteru.

- The Deep Bond: Focus on Arigato (Thank you). In Japanese culture, gratitude is often the highest form of love. Saying "Thank you for being by my side" (Soba ni ite kurete arigato) often hits way harder than "I love you."

- The Big Moments: Save Ai shiteru for when you truly mean that your life is inextricably linked to theirs. Use it when the "the air" is so thick with emotion that only the heaviest word will do.

Stop worrying about finding the "perfect" word. In Japan, love is a verb, not just a noun. It’s in the tea they pour for you. It’s in the way they wait for you at the station. If you want to know how do you say love in japan, the answer is usually: you don't say it. You do it.

Next Steps for You

Check the "temperature" of your relationship before choosing your words. If you're just starting out, a simple Suki desu (I like you/I have feelings for you) is the gold standard for a formal confession. For long-term partners, try shifting your focus to expressions of gratitude, like Itsumo arigato (Thanks for everything/always), which often carries more emotional weight in a Japanese context than a direct "I love you." If you must be direct, Daisuki is your safest and most natural bet for daily affection.