You’re staring at a 9x9 grid. Most of it is empty. There are a few scattered digits—1s, 7s, maybe a lonely 4 in the corner—and it feels like a math test you didn't study for. But here’s the thing: it isn't math. Not even a little bit. If you replaced all those numbers with letters, or emojis, or different types of fruit, the game would work exactly the same way. It’s a game of logic, not arithmetic.

Honestly, the first time I sat down with a puzzle, I thought I had to make the rows add up to a specific sum. I was wrong. The numbers are just symbols. Understanding how do you play sudoku starts with realizing you are just organizing a set of nine unique items so they don't bump into each other.

The Ground Rules

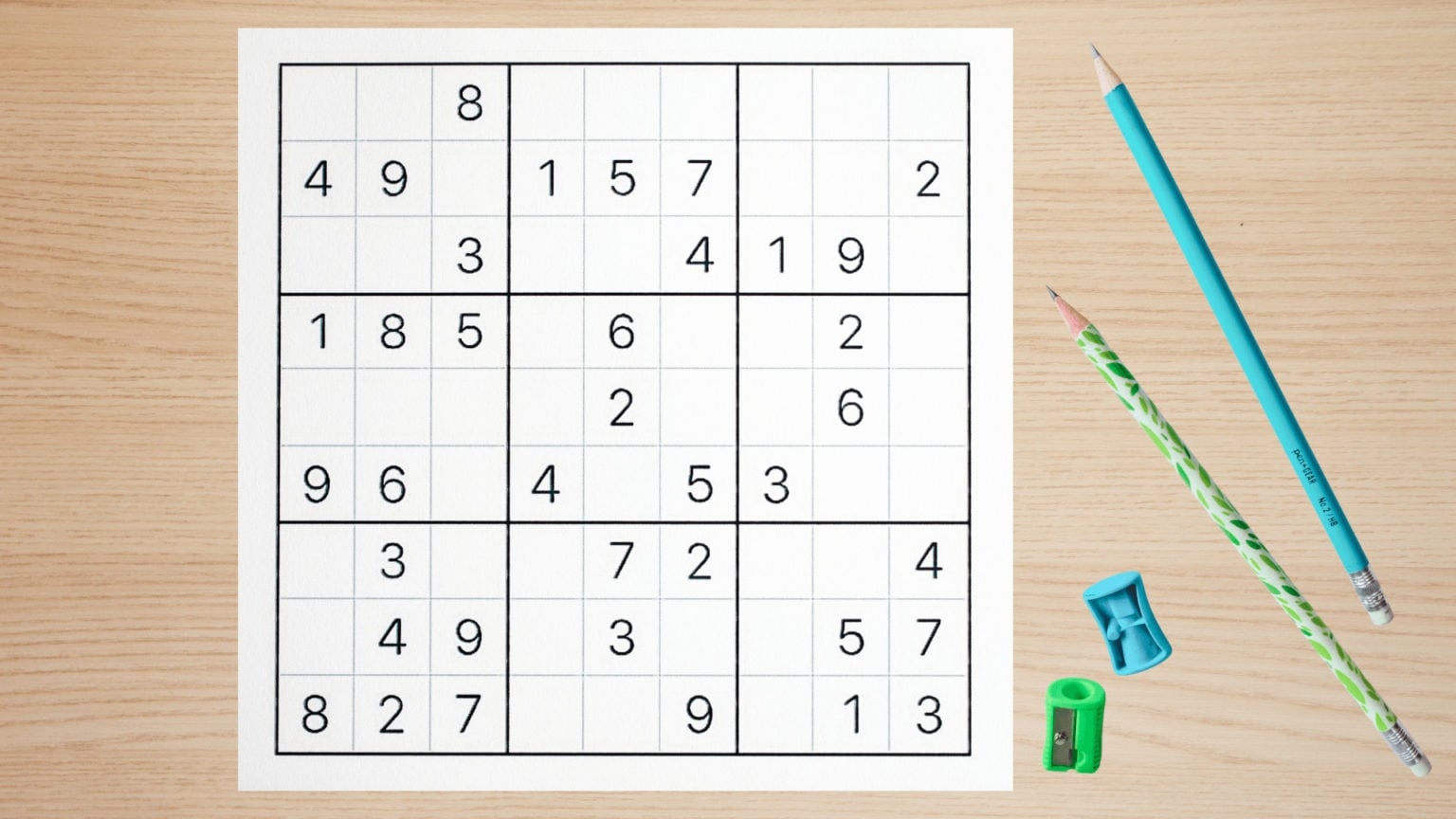

The setup is pretty basic. You have a big square made of 81 smaller cells. This big square is divided into nine 3x3 subgrids, often called "boxes" or "blocks." To win, you have to fill every single cell with a number from 1 to 9.

But there are three unbreakable laws.

First, every horizontal row must contain every number from 1 to 9 exactly once. Second, every vertical column has to do the same. Third, each of those nine 3x3 boxes must also contain every number from 1 to 9 once. If you put a 5 in a row that already has a 5, you've messed up. If you put a 2 in a box that already has a 2, the whole thing breaks. It’s that simple, and that frustrating.

How Do You Play Sudoku Without Losing Your Mind?

Most beginners start by "scanning." It’s the most natural way to play. You pick a number—let’s say 1—and you look at every 3x3 box to see where a 1 could possibly go.

Imagine the top-left box. You look at the rows and columns that intersect that box. If Row 1 already has a 1 somewhere else, then none of the three cells in the top part of your box can be a 1. If Column 2 has a 1, then none of the cells in the middle column of your box can be a 1. By a process of elimination, you eventually find a spot where only one number can live.

It feels like a "gotcha" moment. It’s satisfying.

But what happens when you get stuck? This is where people usually quit. They think they need to guess. Never guess. Sudoku is a solved game; every "true" Sudoku puzzle has exactly one unique solution that can be reached through pure deduction. If you find yourself guessing between a 4 and a 6, you haven't looked hard enough at the other constraints.

The Pencil Mark Method

You’ve probably seen experts' grids covered in tiny, messy numbers. Those are "candidates."

👉 See also: Finding 5 Letter Words With O and S: Why Wordle Pros Obsess Over These Specific Combos

When you can’t immediately place a number, you write down the possibilities in the corner of the cell. If a cell could be a 3, an 8, or a 9, you jot those down. As you fill in other parts of the grid, you cross those tiny numbers off. Eventually, you’ll find a "Naked Single." That’s a cell where, after all the eliminations, only one possible number remains.

There is also the "Hidden Single." This is when a cell could technically hold several numbers, but there is one specific number that can't go anywhere else in that entire row or column. Even if that cell could be a 5 or a 2, if that's the only spot in the row where a 5 can live, then it has to be a 5.

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Tactics

Once you move past the "Easy" settings on your app or the back of the newspaper, the game gets weird. You start needing things with cool names like "X-Wing" or "Swordfish."

Let's look at the "Naked Pair." Suppose you have two cells in the same row that both can only be a 4 or a 7. You don't know which is which yet. However, you do know that those two cells will definitely use up the 4 and the 7 for that row. Because of that, you can safely remove 4 and 7 as possibilities from every other cell in that row. It’s a weirdly powerful way to clear the clutter.

The "X-Wing" is more legendary. It sounds like Star Wars, but it’s actually about patterns in columns. If you find two columns where a specific number can only appear in the same two rows, you’ve formed a rectangle. This means that number must be in those rows for those columns, allowing you to delete that number from every other cell in those two rows across the entire grid.

✨ Don't miss: Universal Pokemon Randomizer ZX: How to Finally Fix Your Boring Replays

Does it sound complicated? Kinda. Does it work? Every time.

Why Does This Game Hook Us?

There is a psychological phenomenon at play here. Humans crave order. We hate "open loops"—unresolved problems or unfinished patterns. A Sudoku grid is the ultimate open loop. According to Dr. Marcel Danesi, a professor at the University of Toronto and author of The Puzzle Instinct, puzzles like Sudoku trigger a dopamine release when we find a "fit."

It’s the same reason we like organizing closets or leveling up in video games. It’s a small, controlled universe where logic always wins. In a world that feels chaotic, Sudoku is perfectly predictable.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- The Double-Up: This is the classic. You’re moving fast, you feel like a genius, and you realize you put two 8s in the same box. In a digital app, it usually highlights red. On paper? You might not realize it for twenty minutes. If you make a mistake, it’s usually better to start over or use a very good eraser. One wrong move cascades through the whole puzzle.

- Over-Marking: If you put pencil marks in every single box for every single number, the grid becomes unreadable. Only mark when you’ve narrowed a cell down to two or three options.

- The Guessing Trap: I mentioned this before, but it bears repeating. If you guess, you aren't playing Sudoku anymore. You're playing a game of chance. If you're stuck, change your perspective. Look at columns instead of rows. Look at the "missing" numbers instead of the ones already there.

The Origins of the Grid

People think Sudoku is ancient Japanese tradition. It isn't. While the name is Japanese (short for Sūji wa dokushin ni kagiru, meaning "the digits must be single"), the modern version was actually designed by an American named Howard Garns in 1979. He called it "Number Place." It didn't really blow up until the mid-80s in Japan, and it didn't become a global obsession until Wayne Gould, a retired judge from Hong Kong, saw a puzzle in a Japanese book and spent six years writing a computer program to generate them.

He eventually convinced The Times in London to publish them in 2004. The rest is history.

Getting Better at the Game

If you want to move from "I sort of get this" to "I can finish a Hard puzzle in ten minutes," you need to practice "Cross-Hatching." This involves looking at a 3x3 box and drawing imaginary lines through it from the numbers in the surrounding rows and columns.

You also need to learn to spot "Triples." This is when three cells in a unit contain only the same three numbers (e.g., 1-2, 2-3, and 1-3). Even if you don't know which cell gets which number, you know those three digits are "claimed."

💡 You might also like: Orders Must Be Followed Uma Musume: Why This Specific Mission Logic Still Confuses Players

It’s basically a game of "If this, then that."

If you're looking for a place to start, many people recommend the New York Times daily puzzles or apps like Good Sudoku. They offer hints that actually explain the logic instead of just giving you the answer.

Actionable Next Steps

To actually master the grid, stop just looking for "where the 1 goes." Try these steps in your next game:

- Focus on the most crowded areas first. The more numbers a row or box already has, the fewer possibilities remain for the empty spots. It's the path of least resistance.

- Use "Snyder Notation" for pencil marks. Only write down a candidate number if it can only fit in exactly two cells within a 3x3 box. This keeps your grid clean and helps you spot pairs instantly.

- Scan the grid by number, not by box. Look at all the 1s. Then all the 2s. This helps your brain see patterns that span across the entire 9x9 board rather than getting "tunnel vision" on one small area.

- Look for the "Full House." This is when a row, column, or box has eight out of nine numbers filled. It's an easy win, but you'd be surprised how often people overlook them while hunting for complex patterns.

- Take a break. If you’ve been staring at a grid for fifteen minutes and haven't placed a single digit, your brain is likely stuck in a loop. Look away. Go for a walk. When you come back, the "hidden" 5 will often jump right out at you.