You’ve been there. You sit down with a fresh sheet of paper, a sharpened 2B pencil, and a burning desire to create a masterpiece. You start sketching. Ten minutes later, you’re staring at a lopsided oval that looks less like a human being and more like a sentient Russet potato. It’s frustrating. It's actually one of the biggest hurdles for any aspiring artist because the human brain is literally hardwired to recognize faces, which means we are incredibly sensitive to even the tiniest mistakes in a drawing.

So, how do you draw heads that actually look, well, like heads?

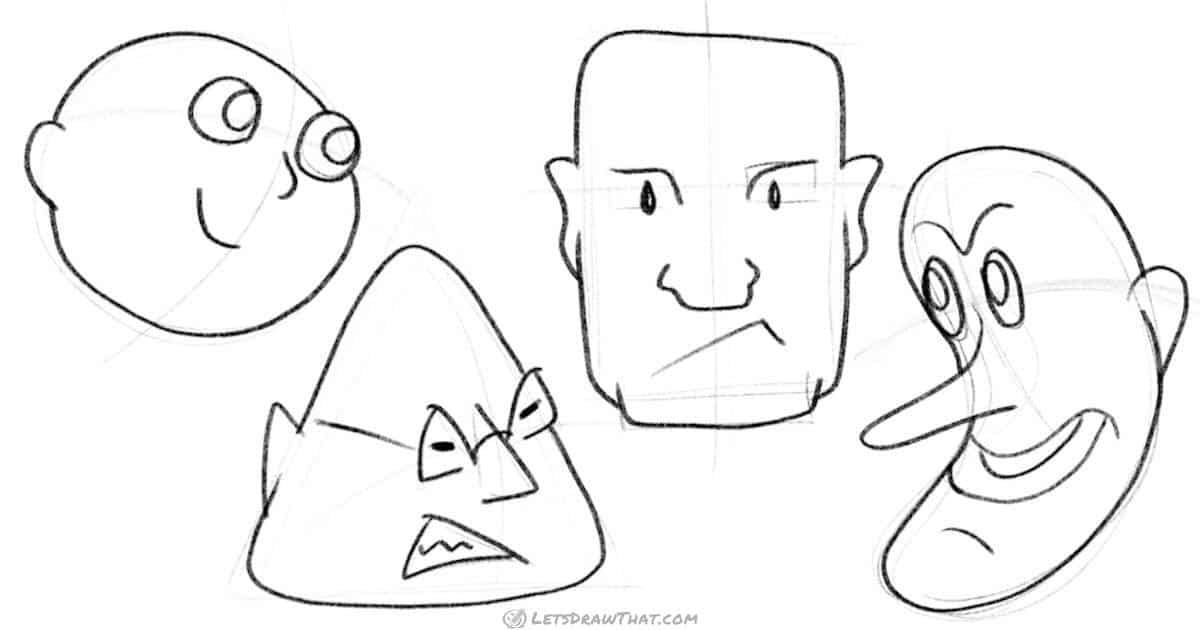

Honestly, most beginners fail because they try to draw the features—the eyes, the nose, the mouth—before they’ve built a house for them to live in. You can’t put a designer sofa in a room that has no walls. If you want to get good at this, you have to stop thinking about "faces" and start thinking about three-dimensional mass. We aren't drawing stickers on a flat surface; we are carving shapes out of space.

The Loomis Method: Why Every Pro Starts With a Ball

If you ask any professional concept artist at Riot Games or a comic book veteran like Jim Lee how they approach the skull, they’ll probably mention Andrew Loomis. Loomis was an illustrator in the mid-20th century who basically cracked the code for constructing the head from any angle. His book, Drawing the Head and Hands, is still the industry bible.

The core idea? The head isn't an egg. It’s a sphere with the sides sliced off.

Think about it. If you take a ball and lop off the left and right sides, you get a shape that mimics the cranium’s flat temporal regions. This is the "Aha!" moment for most students. Once you flatten those sides, you suddenly have a side plane and a front plane.

- Start with a circle. Don't worry about it being perfect.

- Draw a horizontal line across the middle. This is the brow line.

- Chop off the sides. Imagine a smaller circle inside your main circle.

- Drop a line down from the center of that side-circle to find the jaw.

It sounds clinical, but it works. Without this structure, your features will "drift" as you rotate the head. Have you ever drawn a face from a 3/4 view and realized one eye is floating off into the ear territory? That's a lack of Loomis construction.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

Anatomy Isn't Just for Doctors

You don't need to be a surgeon, but you do need to know where the bone is. The skin is just a thin layer draped over a very specific skeletal structure. If you don't understand the landmarks of the skull, your heads will look "mushy."

The zygomatic bone (your cheekbone) is the MVP here. It’s the anchor point for the face. When light hits a head, the cheekbone is usually where that highlight catches before the form drops off into the shadow of the jaw. Then there's the brow ridge. It’s not just a line of hair; it’s a shelf. If you’re drawing a character from a low angle (the "worm's eye view"), that brow ridge will actually hide the top of the eyeballs.

People forget the "keystone" too. That’s the little wedge-shaped area between the eyebrows where the nose connects to the forehead. If you miss that, the nose just looks like it was glued onto a flat mask.

The Rule of Thirds (The Artistic Version)

In a standard, idealized human head, the distance from the hairline to the brow, the brow to the bottom of the nose, and the nose to the bottom of the chin is roughly equal.

- Top Third: Hairline to Brows.

- Middle Third: Brows to Base of Nose.

- Bottom Third: Base of Nose to Chin.

Of course, nobody actually looks like a perfect math equation. If you’re drawing a caricature or a specific person, you find the "likeness" by breaking these rules. Maybe they have a massive forehead. Maybe their jaw is tiny. You start with the "standard" and then push the proportions until it looks like them. But you have to know the standard first.

The Ear is Always Lower Than You Think

This is a hill I will die on. Beginners almost always put the ears too high or too far forward.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

In a profile view, the ear sits behind the vertical midline of the head. It generally aligns between the brow line and the bottom of the nose. If you draw a line back from the eyes, you’re hitting the top of the ear. If you draw a line back from the nostrils, you’re hitting the lobe.

Also, the neck doesn't just stick out of the bottom of the head like a straw in a juice box. It’s an angled cylinder that leans forward. It attaches at the base of the skull (the occipital bone) and wraps around with the sternocleidomastoid muscles—those big ropes that pop out when you turn your head. If you don't connect the head to the neck properly, your drawing will look like a bobblehead.

Lighting: The Secret to Depth

You can have perfect proportions, but if your shading is flat, the head will look flat. You need to identify your light source immediately.

Usually, the "Rembrandt lighting" setup is the easiest to practice. This is where the light comes from 45 degrees above and to the side. It creates a small triangle of light on the shadowed cheek. It forces you to define the bridge of the nose, the socket of the eye, and the underside of the chin.

Stop "smudging" your shadows with your finger. It just makes the drawing look dirty. Use hatch marks or clear, blocked-in shapes of value. Look at the work of George Bridgman. He viewed the human body as a series of interlocking blocks and wedges. It’s aggressive and chunky, but it’s the best way to understand how light wraps around a three-dimensional object.

Misconceptions That are Killing Your Progress

"I just need to find my style."

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

No. Style is what happens when you try to draw correctly and fail in a consistent way. Or, style is an intentional simplification of reality. But you can't simplify what you don't understand. If you try to draw "anime" heads without knowing how a real skull works, your characters will look like they have no brains behind their eyes. The best stylized artists—think Glen Keane (Disney) or Yusuke Murata (One Punch Man)—have a terrifyingly deep understanding of real anatomy. They just choose what to emphasize.

Another one? "I'll just use a reference for everything."

References are great. Use them. But if you rely on them like a crutch, you’ll never be able to draw from your head. You want to reach a point where you understand the concept of a head so well that you can rotate it in your mind. Practice drawing the "Loomis Ball" from twenty different angles in a single sitting. It’s boring. It’s tedious. It’s also how you get good.

Actionable Steps to Improve Right Now

Don't just read this and close the tab. If you actually want to master how do you draw heads, you need to put pencil to paper with a specific plan.

- The 50-Head Challenge: Spend the next week drawing 50 heads. Don't worry about hair or eyes. Just draw the basic Loomis construction—the ball, the sliced sides, the brow line, and the jaw. Do it until you can do it in under 30 seconds.

- Skull Study: Go to a site like Sketchdaily or Pinterest and find photos of actual human skulls. Draw them. Notice where the deep cavities are. Notice how the teeth aren't flat—they sit on a curved muzzle.

- The "No-Eye" Rule: Try drawing a portrait where you don't draw the eyes at all. Just shade the eye sockets as deep, hollow shapes. It forces you to focus on the structure of the brow and cheeks rather than getting distracted by eyelashes and irises.

- Draw From Life: Go to a coffee shop. Sit in a corner. Draw the people around you. They won't sit still, which is actually a good thing. It forces you to capture the "gesture" of the head and the major masses quickly rather than noodling on small details.

Art is a physical skill, like shooting a basketball or playing the cello. Your brain might understand the concept of a "side plane," but your hand has to learn how to execute the curve. Give yourself permission to draw a hundred terrible heads. Eventually, the 101st one will surprise you.

The biggest secret? There is no secret. There's just construction, observation, and a whole lot of scrap paper. Focus on the big shapes first, and the rest will follow. Stop drawing symbols of eyes and start drawing the way the eyelid wraps around the sphere of the eye. Stop drawing a line for a mouth and start drawing the fleshy pillows of the lips. Move from 2D thinking to 3D construction, and you’ll never look at a potato the same way again.