Drawing people is hard. Drawing someone in a stiff, tactical uniform with a dozen pockets, a heavy rifle, and a helmet that never seems to sit quite right on the head? That’s a nightmare for most beginners. When you ask how do you draw a soldier, you aren't just asking for a anatomy lesson. You're trying to figure out how to balance the weight of the gear with the movement of the human body underneath all that Cordura and Kevlar.

If you jump straight into the camouflage patterns, you've already lost. Your drawing will look like a flat, colorful blob.

I’ve seen it a thousand times. Artists get so distracted by the cool "tacticool" accessories—the night vision goggles, the patches, the carabiners—that they forget there is a skeleton inside. If the skeleton is broken, the gear won't save it. We need to talk about posture. Real soldiers rarely stand like statues unless they’re on parade at Arlington. They slouch. They lean. They carry 60 pounds of gear that pulls their shoulders forward.

The Frame: Why Your Soldier Looks Stiff

Start with the gesture. This is the "soul" of the drawing. Most people make the mistake of drawing a soldier standing perfectly straight. In reality, a soldier in the field is usually in a state of "weighted readiness."

Think about gravity.

If you're carrying a heavy ruck, your center of gravity shifts. You lean forward to compensate. To get how do you draw a soldier right, you have to nail this weight distribution. Use a simple action line—a curved stroke from the head down to the lead foot. This defines the energy. If they are holding a carbine, their torso should be slightly bladed, not squared off toward the viewer.

Professional illustrators like Stan Prokopenko often preach that "structure comes before detail." Don't draw the vest yet. Draw the ribcage. Draw the pelvis as a simple box. If those two boxes aren't aligned correctly, your soldier will look like they’re about to tip over.

✨ Don't miss: Getting a Twist Out on Short Natural Hair to Actually Last (and Look Good)

Proportion Hacks for Combat Gear

Standard human proportions usually follow the "eight heads tall" rule. But soldiers are bulky. The helmet adds height. The boots add height. The body armor adds significant width to the torso.

Basically, if you draw a normal person and then "dress" them in gear, they end up looking like a kid wearing their dad's clothes. To fix this, you have to slightly exaggerate the shoulder width of the base frame. A plate carrier (that's the vest that holds the armor) sits high on the chest. It doesn't cover the stomach. Many beginners draw the vest going all the way down to the waist, which makes the character look like they can't even sit down.

Anatomy of the Uniform: Folds and Weight

Uniforms are made of ripstop nylon or heavy cotton blends. This stuff doesn't drape like a silk shirt. It bunches.

When you're figuring out how do you draw a soldier, look at the "points of tension." These are the elbows, the knees, and the crotch. The fabric will radiate out from these points in sharp, zig-zagging folds.

- The "Pipe" Rule: Treat the arms and legs as cylinders. The sleeves should wrap around the cylinder.

- The Overlap: Boots are thick. The pants should bag out over the top of the boot (this is called "blousing").

- Gravity: Pockets on the thighs (cargo pockets) will sag downward if they're full of gear.

Most people mess up the boots. They draw them like sneakers. Combat boots have a thick sole and a rigid heel. They are clunky. If you make them too small, the soldier looks top-heavy. Give them some "clunk."

How Do You Draw a Soldier with Realistic Gear?

The gear is where most people get overwhelmed. There are so many straps.

Actually, don't try to draw every strap. You'll go crazy. Instead, focus on the "silhouette" of the gear. A modern soldier usually wears a Load Bearing Vest (LBV) or a Plate Carrier. This sits over the torso.

Then you have the MOLLE system (Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment). Those are the horizontal rows of webbing you see on tactical vests. You don't need to draw every single stitch. Just a few horizontal lines to imply the texture is enough. Honestly, less is more here. If you over-detail the vest, the eye won't know where to look.

The Helmet and Face

The helmet is basically a bowl. But it's a bowl that sits low on the forehead.

A common mistake is showing too much of the forehead. The rim of the helmet should be just above the eyes. And don't forget the chin strap! It follows the jawline and secures under the chin. If you leave the strap out, the helmet looks like it's just floating there.

For the face, keep it simple. Soldiers are often exhausted or focused. A "thousand-yard stare" is achieved by slightly drooping the eyelids and keeping the mouth neutral. No need for heroic grins. War is tiring.

Weapons: Don't Fake the Geometry

If you're going to include a rifle, you have to get the perspective right. A rifle is a collection of rectangles and cylinders.

If the soldier is holding the weapon in a "low ready" position, the barrel points toward the ground. If they are aiming, the stock must be tucked firmly into the "pocket" of the shoulder. This is a huge detail people miss. The gun doesn't just sit on the chest; it's braced against the body.

James Gurney, a master of realistic rendering, always suggests using reference photos for mechanical objects. You don't have to be an expert on firearms, but you should know where the magazine goes and where the trigger is.

✨ Don't miss: Wishes for Rosh Hashanah: What Most People Get Wrong

Camouflage: The Great Art Killer

Here is a secret: do not draw the camo pattern until the very end.

If you start drawing the little splotches of MultiCam or Woodland camo too early, you'll lose the sense of light and shadow. Shade the entire drawing first. Use a light source—maybe the sun is hitting them from the top right. Create your darks and lights.

Only once the form looks 3D should you "map" the camo pattern over the top. Use a low-opacity pencil or a light wash. The pattern should follow the folds of the cloth. If the fabric folds in, the camo pattern should disappear into that fold.

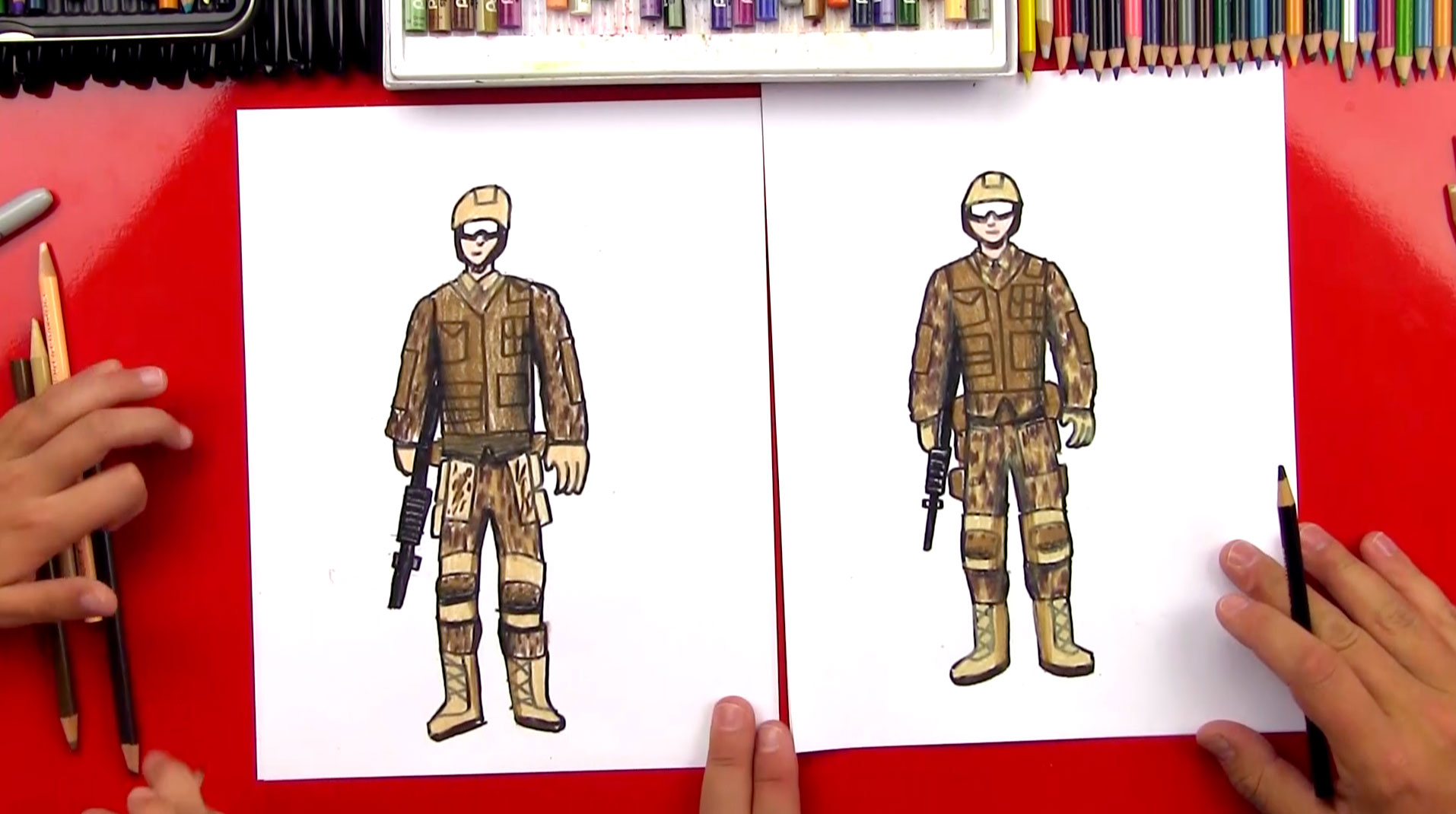

Actionable Steps for Your Next Sketch

Stop thinking about "a soldier" as a generic icon. Think about the story. Is this a soldier from the Civil War? A futuristic space marine? A modern infantryman in a desert? The gear tells the story.

- Sketch the "Skeleton" First: Use a 2-minute gesture drawing. No details. Just the pose. If the pose is boring, the drawing is boring.

- Add the Armor "Blocks": Draw the helmet and the chest plate as solid geometric shapes. This gives the character bulk.

- Define the Limbs: Add the baggy sleeves and trousers. Remember the "tension points" at the joints.

- Layer the Gear: Add the rifle, the backpack, and the pouches. Make sure the straps look like they are actually pulling on the fabric.

- Shade Before Texture: Get the shadows right. Use a 2B pencil to darken the areas under the vest and inside the folds.

- Lightly Apply Pattern: Add the camo splotches last, making sure they "bend" with the curves of the body.

The most important thing to remember when asking how do you draw a soldier is that they are human beings first, and combatants second. Their clothing is functional. Everything they wear has a purpose and a weight. If you can make the viewer feel that weight, you've succeeded.

Get a sketchbook. Go to a park or a coffee shop and look at how people carry heavy backpacks. That slouch? That's your foundation. Master the slouch, and the soldier will follow. Focus on the silhouette and the way the fabric reacts to the heavy items tucked into the pockets. Once you nail the physics of the clothing, the rest—the guns, the goggles, the patches—is just decoration. You've got this. Just keep the lines loose and the weight heavy.