You've probably seen the videos. Boston Dynamics’ Atlas doing backflips or Tesla’s Optimus trying to fold a shirt. It looks like magic. But if you’ve ever tried to sit down and ask, how do we make a robot from scratch, you quickly realize the gap between a YouTube demo and a functional machine is massive. It’s a mess of burnt out servos, incompatible Python libraries, and the crushing realization that gravity is a jerk. Building a robot isn't just about bolting metal together; it’s about tricking physics into behaving.

The Skeleton and the Muscle: Mechanics Matter

Most people start with the brain. Big mistake. If your mechanical foundation is trash, the smartest AI in the world can’t save it. You need a chassis.

📖 Related: The 92 Percent of Data is Dark: What It Means for Your Privacy and Business

Think about the "Degrees of Freedom" (DoF). This is basically just a fancy way of saying "how many ways can this thing move?" A human arm has seven. If you’re building a simple rover, you might only need two. But the moment you want a gripper to pick up a coffee mug, the math gets ugly. You have to choose your actuators carefully. DC motors are cheap and fast, but they have no "memory" of where they are. Stepper motors are precise but power-hungry. Servos? They’re the middle ground, but cheap ones will jitter until you want to throw them out the window.

Materials change everything too. Carbon fiber is great if you’re rich. 3D-printed PLA is fine for prototyping, but it melts if you leave it in a hot car. Real industrial robots often use machined aluminum for that sweet spot of strength-to-weight ratio. Honestly, your first build will probably be held together with zip ties and prayers. That's okay. Even the pros at NASA started somewhere.

Sensing the World Without Crashing Into It

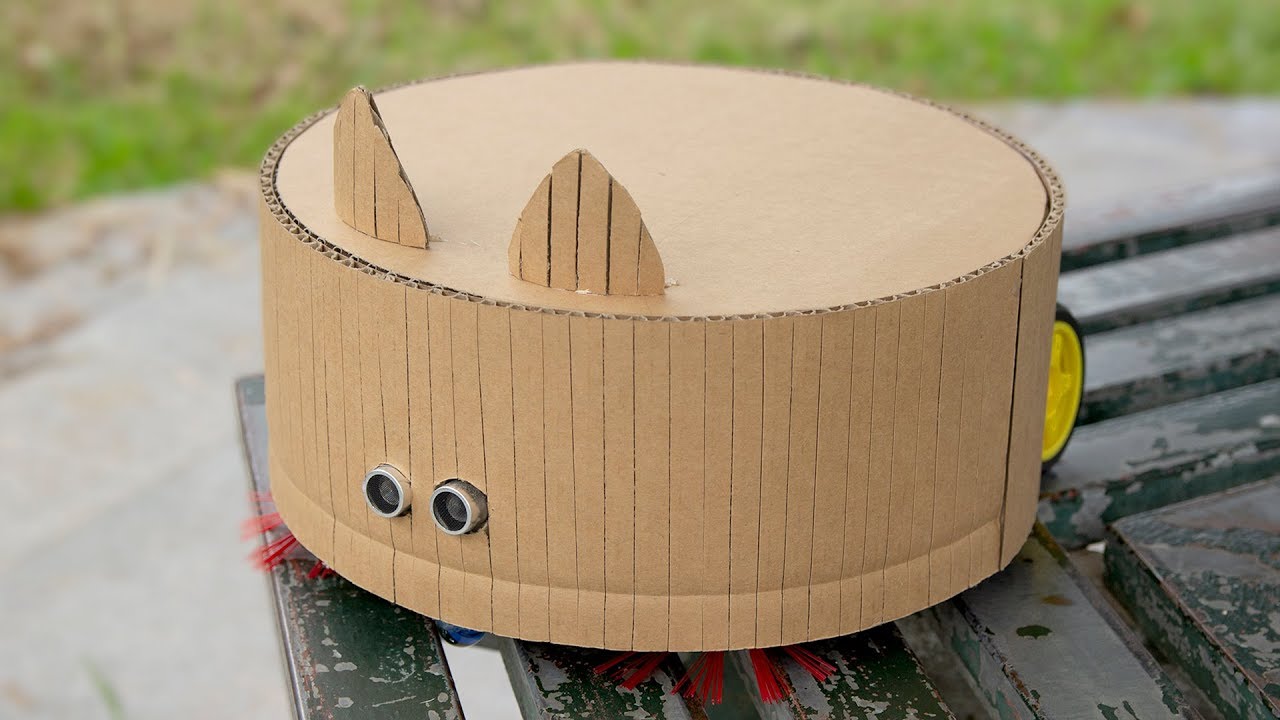

A robot without sensors is just a roomba with a death wish. To answer how do we make a robot that doesn't just spin in circles, you need to give it "proprioception"—the ability to know where its own body parts are.

🔗 Read more: iPhone JPEG to JPG: Why Your Photos Keep Changing and How to Fix It

- Lidar and Ultrasonic: These are the eyes. Lidar uses lasers to map a room in 3D, while ultrasonic sensors work like a bat’s ears.

- IMUs (Inertial Measurement Units): This is the inner ear. It tells the robot if it's tilting or falling.

- Encoders: These count how many times a wheel has turned. Without them, your robot has no idea if it’s moved five inches or five miles.

It's not just about having sensors; it’s about sensor fusion. This is the process of taking data from a grainy camera, a noisy IMU, and a wonky distance sensor and blending them into a single "truth." If the camera says there’s a wall but the bumper says there isn't, who does the robot believe? Programmers spend months on this. They use Kalman filters—complex probabilistic math—to help the robot make its best guess.

The Brain: ROS, Python, and the Logic Gap

Here is where the "intelligence" happens. Most modern robotics experts use ROS (Robot Operating System). It’s not actually an operating system like Windows; it’s a middleware framework. It lets different parts of the robot talk to each other. The "arm" node can tell the "camera" node to look at a specific coordinate without you having to write 5,000 lines of custom communication code.

You'll likely be coding in C++ for the heavy lifting and Python for the high-level logic. Why? Because C++ is fast. When a robot is about to fall over, it needs to calculate its center of mass in microseconds. Python is too slow for that, but it’s great for "recognizing a cat" or "navigating to the kitchen."

The Reality of Artificial Intelligence

Don't confuse "robotics" with "AI." They overlap, but they aren't the same thing. You can have a very complex robot that uses zero AI—just pure, hard-coded geometry and physics. However, if you want your robot to handle the "unstructured" world (like a messy bedroom), you need Machine Learning. This involves training models on thousands of images so the robot knows a sock isn't a solid obstacle.

👉 See also: Why the Seiko TV Watch 1982 Was Actually Decades Ahead of Its Time

Power is the Silent Killer

You can build the most beautiful, intelligent machine, and it will be useless if it dies in ten minutes. Power density is the biggest bottleneck in robotics today. Lithium-polymer (LiPo) batteries are the standard because they pack a punch, but they are also essentially spicy pillows that can explode if you mistreat them.

You have to calculate the "current draw" of every motor. If your robot tries to lift something heavy, the motors will suck more power, potentially dropping the voltage so low that the onboard computer reboots. It’s a constant balancing act. Engineers use buck converters to step down voltage for the electronics while keeping the raw power flowing to the motors. It's a literal electrical tightrope.

How Do We Make a Robot That Actually Ranks and Discovers?

If you are documenting this process to get noticed on Google or land in Google Discover, you have to stop writing like a textbook. Google's 2026 algorithms crave "Information Gain." They don't want another article that defines what a robot is. They want your specific failures.

- Show the video of the robot falling over.

- Explain the specific error code that took you three days to fix.

- Use high-resolution, original images. Stock photos of "blue holograms" are the fastest way to get ignored.

Google Discover specifically loves "how-to" content that feels personal and timely. If you're using a specific new microcontroller like the latest Raspberry Pi or an NVIDIA Jetson, mention it early. People search for parts as much as they search for concepts.

What Most People Get Wrong

People think robots are smart. They aren't. They are incredibly literal. If you tell a robot to "go through the door" and the door is closed, a dumb robot will just hit the door until its motors burn out. Making a robot "smart" is really just the process of accounting for every possible way things can go wrong. It's 10% cool engineering and 90% edge-case management.

Start With These Steps

Stop overthinking and start breaking things.

- Buy a Kit: Don't try to machine your own gears on day one. Get an Elephant Robotics or a TurtleBot kit. See how the software interacts with the hardware first.

- Master the Simulation: Use Gazebo or NVIDIA Isaac Sim. It’s free to crash a digital robot. It’s expensive to crash a physical one.

- Focus on One Task: Don't build a "butler." Build a robot that can find a red ball. That’s it. Once it can do that 100% of the time, move to the next thing.

- Join the Community: Spend time on the ROS Discourse or certain subreddits. The documentation for most robotics libraries is... let's say "optimistic." You'll need real human advice to get through the bugs.

Build the base. Get the motors spinning. Figure out the power. Only then should you worry about making it "smart." Robotics is a marathon of frustration, but seeing something you built move on its own for the first time? Nothing beats that feeling.