You’ve probably looked through a pair of binoculars or a cheap plastic telescope and wondered how a few pieces of glass can make a crater on the Moon look like it’s right in your face. It feels like magic. It isn't. It’s actually just a very clever way of "bending" reality—or at least, bending the path that light takes before it hits your eye.

When people ask how do optical telescopes work, they usually expect a complicated lecture on physics. Honestly? It’s simpler than that. At its core, a telescope is just a light bucket. Imagine standing in a rainstorm with a thimble. You aren't going to catch much water. Now, swap that thimble for a massive 10-foot wide funnel. Suddenly, you’re drowning in water. A telescope does the exact same thing, but with photons instead of raindrops. Your eye is the thimble. The telescope is the giant funnel.

The Big Lie About Magnification

Let's clear something up right now because it drives astronomers crazy. Most beginners think telescopes are all about magnification. They go to a big-box store, see a box that screams "500X ZOOM!" and think they’ve found a winner.

Wrong.

Magnification is actually the least important part of how a telescope functions. You can magnify a blurry image as much as you want, but you’re just making a bigger, blurrier image. The real secret is aperture. This is the diameter of the main lens or mirror. The bigger the aperture, the more light the telescope "collects." More light means you can see fainter objects, like distant nebulae or the moons of Jupiter, that your naked eye would never even know existed.

The Two Main Ways to Build a Light Bucket

There are basically two ways to bend light to your will. You either use a lens or you use a mirror. This divides the world of optical telescopes into two main camps: Refractors and Reflectors.

Refractors: The Classic Spyglass

If you picture a pirate or Galileo, you’re thinking of a refracting telescope. These use a glass lens at the front to bend—or refract—light as it passes through. The light travels down the long tube and hits a focal point where the image is formed.

It sounds straightforward, but glass is heavy. If you want a bigger lens, it gets exponentially heavier and more expensive. Also, light is a bit of a diva. Different colors of light (wavelengths) bend at different angles. This leads to something called chromatic aberration, where you see weird purple or blue halos around bright stars. To fix this, manufacturers have to use multiple lenses made of exotic materials like fluorite, which is why a high-end "Apochromatic" refractor can cost more than a used car.

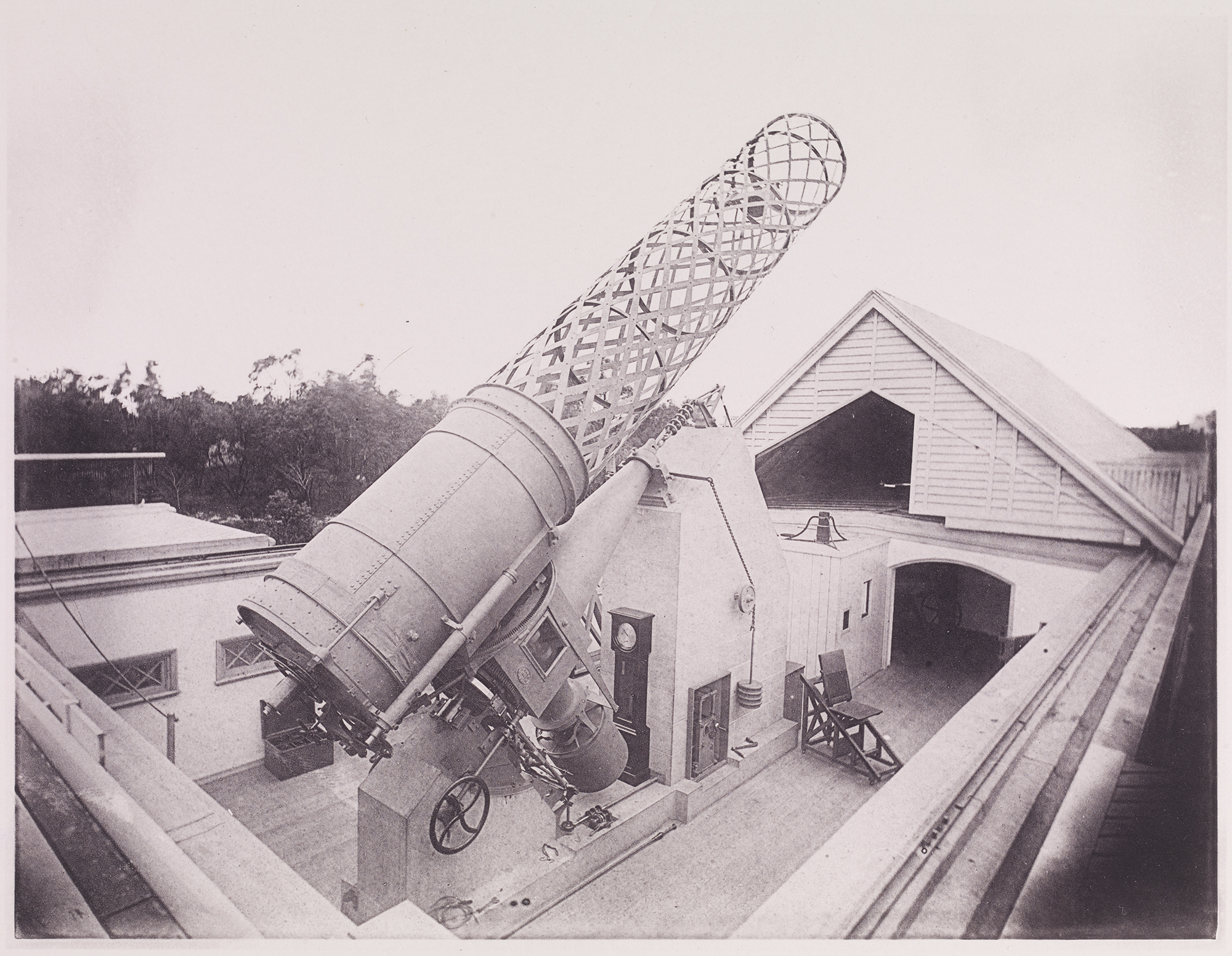

Reflectors: The Mirror Revolution

Sir Isaac Newton looked at refractors and thought, "There has to be a better way." He swapped the heavy lens at the front for a curved mirror at the back.

In a reflecting telescope, light enters the open tube, hits the primary mirror at the bottom, and bounces back up. Before it exits the tube, a small secondary mirror tilts the light 90 degrees into an eyepiece on the side. This is the "Newtonian" design. Since mirrors only have one surface to polish and can be supported from the back, they can be massive. The Keck Observatory in Hawaii uses mirrors that are 10 meters across. You couldn't do that with a lens; it would sag under its own weight like a piece of warm taffy.

How the Eyepiece Actually Works

If the big mirror or lens (the objective) does the heavy lifting of gathering light, the eyepiece is the "magnifying glass" that lets you actually see it. This is a common point of confusion. The telescope creates a tiny, incredibly bright image at the "focal plane." You then use the eyepiece to look at that tiny image.

You can swap eyepieces to change the magnification. If you want to see the whole Moon, you use a long focal length eyepiece (like a 25mm). If you want to see the "Great Red Spot" on Saturn, you swap to a short one (like a 6mm). But remember the rule: you are limited by the atmosphere. On a "wavy" night where the air is turbulent, high magnification will just show you a shimmering mess. Professional astronomers call this "seeing," and it’s why they build telescopes on top of mountains or launch them into space.

Catadioptrics: The Best of Both Worlds?

Then there are the "hybrids." You've likely seen these short, squat telescopes called Schmidt-Cassegrains (SCTs). They use both mirrors and lenses.

Light hits a thin "corrector plate" (a lens) at the front, bounces off a mirror at the back, hits a mirror at the front, and then travels back through a hole in the main mirror to the eyepiece. It's a "folded" optical path. This allows a telescope with a very long focal length to fit into a tiny bag. They are the SUVs of the telescope world—good at everything, though maybe not the absolute best at any one specific thing.

Why Can't We Just See the Flag on the Moon?

This is a question that pops up every time someone buys their first scope. "Can I see the Apollo landing sites?"

No. You can't. Not even with the Hubble Space Telescope.

It comes down to diffraction limits. Physics has a speed limit, and it also has a resolution limit. To see something as small as a flag or a lunar rover from Earth, you would need a telescope with a mirror hundreds of meters wide. Light waves actually interfere with each other as they pass through the aperture. This creates a "blur" that prevents you from seeing infinite detail. Even the most perfect mirror is bound by the laws of physics.

Real-World Limitations and the "Atmospheric Tax"

Living at the bottom of an atmosphere is like trying to birdwatch from the bottom of a swimming pool. The air is constantly moving, shifting, and glowing. This is why how do optical telescopes work in a lab is very different from how they work in your backyard.

- Light Pollution: If you live in a city, the atmosphere reflects the orange glow of streetlights. This washes out the faint contrast of galaxies.

- Thermal Equilibrium: If you take a warm telescope out of a heated house into a cold night, the air inside the tube will swirl. This creates "tube currents" that ruin the image. You have to let the glass cool down to the outside temperature before it performs well.

- Collimation: Mirrors can wiggle. Reflecting telescopes need to be "collimated," which is just a fancy word for aligning the mirrors so they point exactly at each other. If they’re off by even a millimeter, stars will look like little seagulls instead of pinpoints.

The Human Element: Your Eyes Matter

Interestingly, your own biology plays a role. When you look through a telescope at night, your eyes undergo "dark adaptation." It takes about 20 to 30 minutes for your pupils to fully dilate and for your retina to produce rhodopsin (visual purple). One glimpse of a smartphone screen or a porch light ruins this instantly.

Experienced observers also use a trick called averted vision. The center of your eye (the fovea) is great at detail but terrible at low light. The edges of your retina are much more sensitive to faint light. If you want to see a faint nebula, you don't look directly at it. You look slightly to the side, and the object will "pop" into view. It feels counterintuitive, but it’s a biological hack for better stargazing.

The Shift to Digital

While we’re talking about optical telescopes, we have to acknowledge that the "eyepiece" is slowly dying in professional circles. Most modern telescopes use CCD or CMOS sensors—essentially high-powered versions of the sensor in your phone.

These sensors have a much higher "quantum efficiency" than the human eye. Your eye sees in "real-time," but a sensor can sit there and soak up light for 10 minutes, 20 minutes, or 10 hours. This is why photos of galaxies look so much more colorful and detailed than what you see through the glass. Your eye can't "stack" light; a computer can.

📖 Related: Cell phone holders for cars: What most people get wrong about safety and grip

Practical Steps for Your Stargazing Journey

If you’re actually interested in seeing this for yourself, don't just run out and buy the first thing you see online. Start with these steps:

- Download a Star Map App: Use something like Stellarium or SkySafari. Hold it up to the sky. Learn where the bright stuff is before you try to point a telescope at it.

- Buy Binoculars First: Seriously. A pair of 7x50 or 10x50 binoculars is basically two small refracting telescopes joined together. You can see the craters of the moon, the moons of Jupiter, and even the Andromeda Galaxy with them. Plus, they don't require setup.

- Join a Local Astronomy Club: Most clubs have "star parties." This is the best way to see different types of telescopes (Refractors, Reflectors, and SCTs) in action. Astronomers love showing off their gear. You can look through a $5,000 setup for free and see if it's actually for you.

- Focus on the Mount: A $1,000 telescope on a $10 tripod is a $10 telescope. If the mount shakes every time you breathe, you won't see anything. Stability is more important than optics for a beginner.

Optical telescopes are remarkable because they haven't fundamentally changed in centuries. Whether it's the glass lens used by Galileo or the gold-plated mirrors of the James Webb, the goal remains the same: capture as many photons as possible and bring them to a sharp, clear focus. Understanding that it’s about light collection—not "zooming in"—is the first real step toward mastering the night sky.