Ever stared at a blister pack of pills and wondered who on earth came up with a name like Xeljanz or Wegovy? It feels like someone just threw a handful of Scrabble tiles at a wall and called it a day. But honestly, the process of how do drugs get their names is one of the most bureaucratic, expensive, and strangely poetic grinds in the modern business world. It isn't just one name, either. Every drug you take is essentially a person with three different identities: a chemical name that only a lab tech could love, a generic name that sounds like a Star Wars planet, and a brand name designed by high-end marketing firms to make you feel "vibrant" or "unstoppable."

It’s a mess. A high-stakes, multi-million dollar mess.

The Three-Identity Crisis

Before a drug even hits a shelf, it has to survive a naming gauntlet. First comes the chemical name. This describes the molecular structure. If you’ve ever seen something like (+)-(S)-4-[4-(dimethylamino)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-hydroxybutyl]-3-(hydroxymethyl)benzonitrile, you’re looking at the raw DNA of a drug. Nobody is going to ask for that at a CVS.

Next is the generic name, or the non-proprietary name. This is where things get technical but slightly more readable. Think ibuprofen or sildenafil. These names aren’t just random; they use "stems" to tell doctors what the drug actually does. If a name ends in -mab, it’s a monoclonal antibody. If it ends in -stat, it’s likely a cholesterol-lowering HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor.

Then, there’s the brand name. This is the "Lexus" or "iPhone" of the drug world. This is Advil or Viagra. This name has one job: to be memorable and sell.

Who Actually Decides This Stuff?

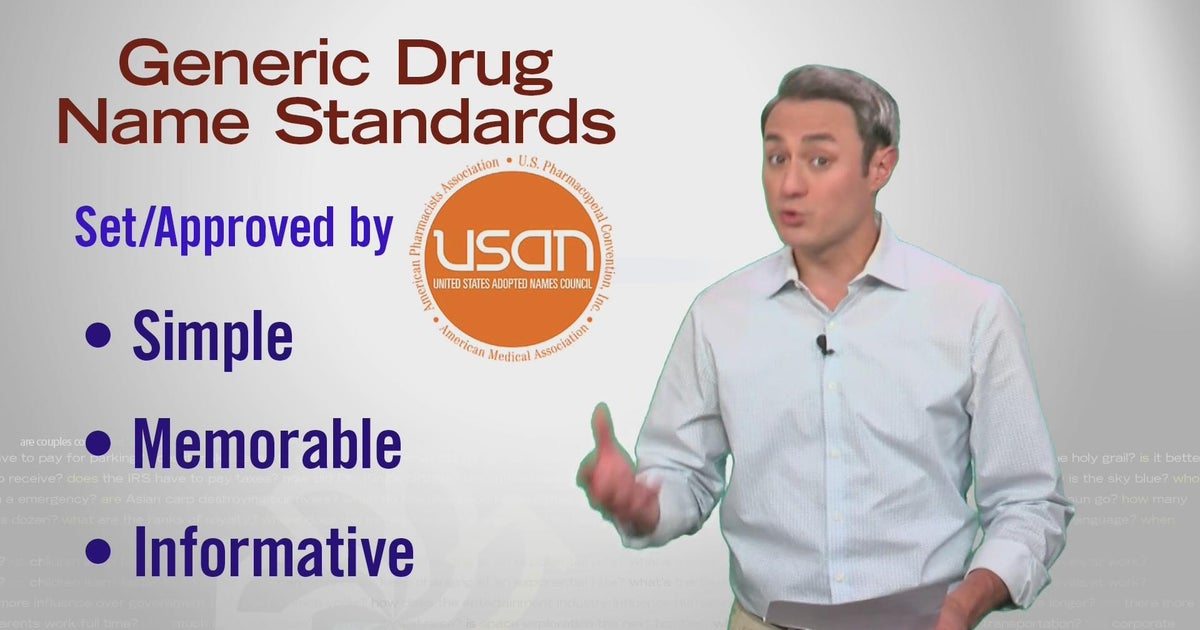

You can't just name a drug "HappyPill" and call it a day. The United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council and the World Health Organization (WHO) oversee the generic names. They want consistency. They want to make sure that if a doctor in Tokyo and a doctor in Des Moines prescribe a generic, they are talking about the exact same chemical.

🔗 Read more: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

For brand names, the FDA (specifically the Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis) has the final say in the U.S. They are the ultimate buzzkills, but for a good reason. They reject about 30% to 40% of the names pharmaceutical companies propose. Why? Because of "look-alike, sound-alike" errors. If a new heart medication sounds too much like an existing cough syrup, people die. It’s that simple.

The Psychology of the "X" and "Z"

Have you noticed how many new drugs have the letters X, Z, Q, or V? Xarelto. Zyprexa. Quviviq. There’s a psychological trick happening here. Linguists and branding experts—firms like Interbrand or Brand Institute—know that "plosive" consonants (letters like P, T, K, B, D, G) and high-value Scrabble letters feel "cutting edge" and "powerful."

A name starting with "Z" feels fast and modern. A name with a "V" often implies vitality or life (think Viagra, derived from virility and Niagara).

The High Cost of a Name

Pharmaceutical companies spend upwards of $250,000 to $500,000 just on the naming process. This involves linguistic checks in dozens of languages. You don't want to name a blockbuster drug something that means "diarrhea" in a foreign dialect. It happened to the Chevy Nova (which supposedly meant "doesn't go" in Spanish, though that's largely an urban legend), and pharma companies are terrified of a similar blunder.

They test for "connotative" meaning. Does the name sound too much like a competitor? Does it sound too much like a street drug? Does it make an illegal claim? Under FDA rules, a drug name cannot be "overly promotional." You can’t call a weight loss drug "Fat-B-Gone." That’s why we get Zepbound instead. It hints at the result without legally promising it in the title.

💡 You might also like: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

Real Examples of Naming Logic

Let’s look at some specifics to see how do drugs get their names in the real world:

- Lasilix (Furosemide): This is a diuretic used to treat fluid build-up. Its name is a play on the fact that it "lasts six" hours.

- Premarin: This one is a bit gross if you're squeamish. It’s an estrogen replacement. The name comes from Pregnant mare urine. Because that's exactly where the hormone was originally sourced.

- Vicodin: The "Vi" comes from the Roman numeral VI (6) because it is reportedly six times as strong as codeine ("codin").

- Ambien: This name is meant to evoke "AM" (morning) and "bien" (good). Basically, "have a good morning" because you actually slept.

The Stem System: The Secret Language of Doctors

If you want to understand the "secret code" of drug names, you have to look at the suffixes. This is the most structured part of the chaos.

- -prazole: These are proton pump inhibitors for acid reflux (Omeprazole, Nexium).

- -afil: These are PDE5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunction (Sildenafil, Tadalafil).

- -azepam: These are benzodiazepines for anxiety (Diazepam, Lorazepam).

- -olol: These are beta-blockers for high blood pressure (Atenolol, Metoprolol).

Generic names are basically LEGO sets. The "stem" tells you the family, and the prefix is just there to distinguish it from its cousins.

Why the FDA Rejects Names

The FDA uses a tool called the Phonetic and Orthographic Computer Analysis (POCA). This software compares a proposed name against a database of every other drug name on the market. If the score is too high, the name is dead.

They also worry about handwriting. Even in our digital age, messy prescriptions happen. If "Celebrex" (for arthritis) looks too much like "Celexa" (for depression) when scribbled on a pad, the pharmacist might give the patient the wrong one. This happened enough that the FDA forced the manufacturers to change how they communicate these drugs.

📖 Related: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

The Rise of the "Fantasy" Name

In the 1950s and 60s, drug names were boring. They were often just shortened versions of the chemical name. Then came the era of "suggestive" names like Halcion (peaceful). Now, we are in the era of "abstract" names.

Wegovy and Ozempic don't really "mean" anything in English. They are empty vessels. This is a brilliant marketing move. When a word has no pre-existing meaning, the company can spend billions of dollars in advertising to create the meaning from scratch. When you hear "Ozempic," you think of weight loss and that catchy "Oh, oh, oh" jingle. The name is a blank canvas for the brand's identity.

Moving Beyond the Hype

Understanding how do drugs get their names helps demystify the medical process. It takes the "magic" out of the pill and reminds you that this is a product—a mix of chemistry, law, and high-level marketing.

Next time you look at a prescription bottle, try to find the "stem." It’ll tell you more about what’s happening in your body than the fancy brand name on the front of the box ever will.

Actionable Insights for Navigating Drug Names:

- Check the Stem: Look at the last 4-6 letters of your generic medication. Search for "drug name stems" online to see what class of medication you’re actually taking. This helps you understand potential side effects shared by that whole family of drugs.

- Use Tall Man Lettering: If you are a healthcare provider or even a patient organizing your own meds, use "Tall Man" lettering to distinguish similar drugs (e.g., buPROPion vs. busPIRone).

- Verify with the Pharmacist: Always ask, "What is this for?" when picking up a prescription. If the name sounds like something else you've taken but the purpose is different, you might have flagged a "look-alike, sound-alike" error before it starts.

- Request Generics by Name: Many brand names are just expensive labels for generics that have been around for decades. Knowing the generic name allows you to shop for the lowest price across different pharmacies.

The naming process is a weird bridge between science and capitalism. It’s designed to be safe, but it’s also designed to be profitable. Now you know how to see through both.