You’re sitting there after a massive bowl of spicy pasta or maybe that third cup of coffee, and suddenly, it hits. That familiar, gnawing burn in your chest. Your first instinct? Grab a roll of Tums or a bottle of Maalox. Most of us don't even think about it. We just want the fire to stop. But have you ever actually stopped to wonder, how do antacids work exactly? It’s not magic, though it feels like it when that burning sensation vanishes in minutes.

It's basic chemistry. Honestly, it's the kind of stuff you probably slept through in 10th-grade science class, but now that your esophagus is screaming, it suddenly feels very relevant.

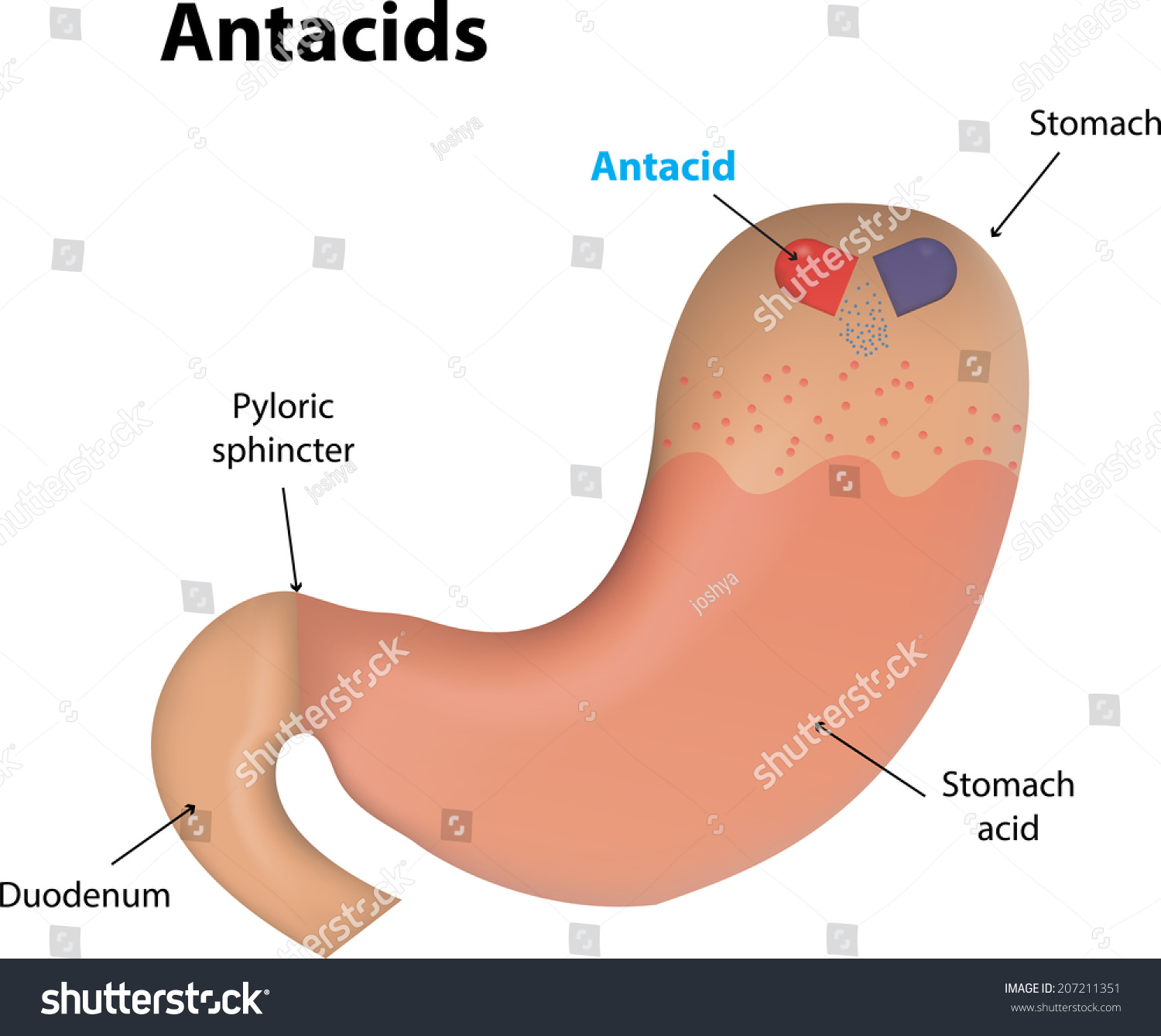

Your stomach is a literal acid vat. It contains gastric juice, primarily hydrochloric acid (HCl), which sits at a pH of about 1.5 to 3.5. That is incredibly acidic. It’s strong enough to dissolve metal, yet your stomach lining usually handles it just fine thanks to a thick layer of mucus. The problem starts when that acid escapes. When the lower esophageal sphincter—the little muscular valve that’s supposed to keep things headed downstream—gets floppy or fails, acid splashes up. That’s heartburn.

The Chemistry of the Quick Fix

Antacids are essentially "bases" or alkaline substances. If you remember the pH scale, acids are on the low end and bases are on the high end. When you mix them, they neutralize each other. This is a classic neutralization reaction.

✨ Don't miss: Is the Waterpik Aquarius Professional Water Flosser Still the Gold Standard for Your Teeth?

Most over-the-counter (OTC) antacids use a few specific active ingredients: calcium carbonate, magnesium hydroxide, aluminum hydroxide, or sodium bicarbonate. When these hit your stomach, they react with the hydrochloric acid to create water and salt.

Take Tums, for example. The active ingredient is calcium carbonate ($CaCO_3$). When it meets your stomach acid ($HCl$), the chemical reaction looks like this:

$$CaCO_3 + 2HCl \rightarrow CaCl_2 + H_2O + CO_2$$

The result? You’ve turned burning acid into calcium chloride (a salt), water, and carbon dioxide. This is why you often burp after taking an antacid. That $CO_2$ has to go somewhere.

Why Some Antacids Make You Run to the Bathroom

Not all antacids are created equal. You’ve probably noticed that some brands emphasize "extra strength" while others focus on "fast-acting." The choice of metal—calcium, magnesium, or aluminum—matters more than you think because they all have different side effects on your digestive tract.

Magnesium-based antacids, like Milk of Magnesia, are famous for their laxative effect. Magnesium draws water into the intestines, which speeds things up. On the flip side, aluminum-based antacids tend to cause constipation. They slow down the muscular contractions in your gut.

Because of this, many manufacturers (think Mylanta or Maalox) actually combine aluminum and magnesium. They’re trying to balance the two out so you don't end up with either extreme. It’s a bit of a pharmacological tug-of-war happening in your intestines.

Then there’s sodium bicarbonate—good old baking soda. Alka-Seltzer is the big name here. It works incredibly fast because it’s highly soluble, but it’s also loaded with salt. If you’re watching your blood pressure, slamming sodium bicarbonate isn't always the best move. Plus, the massive release of gas can lead to "gastric distension," which is just a fancy way of saying you’ll feel incredibly bloated until you let out a massive belch.

How Do Antacids Work Differently From H2 Blockers?

This is a huge point of confusion. You walk into a CVS and see a wall of boxes: Tums, Pepcid, Prilosec. They aren't the same thing.

Antacids are the "I need help right now" option. They neutralize the acid that is already there. They don’t stop your body from making more. They are purely reactive.

H2 blockers (like famotidine, found in Pepcid) work by blocking the histamine receptors in your stomach that signal the cells to pump out acid. They take about 30 to 60 minutes to kick in, but they last much longer—usually 8 to 12 hours.

Then you have Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) like Prilosec (omeprazole). These are the heavy hitters. They don’t just block a signal; they actually shut down the "pumps" in your stomach cells that produce acid. These aren't for occasional heartburn from a slice of pizza; they are designed for chronic issues like GERD (Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease).

The Danger of the "Acid Rebound"

Your body is smarter than you give it credit for. It likes homeostasis. When you dump a bunch of alkaline tablets into your stomach and the pH levels spike, your stomach cells sometimes panic. They sense that the acid level has dropped too low and respond by cranking up the production of gastrin, a hormone that tells your stomach to make even more acid.

This is called acid rebound.

It’s a vicious cycle. You take an antacid, you feel better, the antacid wears off, and then your stomach pumps out a surplus of acid to compensate. Suddenly, you’re reaching for more tablets. If you find yourself chewing antacids like they’re candy every single day, you aren't just treating a symptom; you might be making the underlying environment worse.

Real-World Risks Most People Ignore

We tend to treat antacids like snacks, but they are drugs. And they interact with other drugs.

Because antacids change the pH of your stomach, they can mess with how your body absorbs other medications. Many pills are designed to dissolve at a specific acidity level. If you take an antacid at the same time as, say, certain antibiotics (like tetracycline or fluoroquinolones) or antifungal meds, the antacid can bind to the medication and prevent it from ever entering your bloodstream. You’re basically flushing your expensive prescription down the toilet.

There’s also the issue of "Milk-Alkali Syndrome." It’s rare but serious. If you consume massive amounts of calcium carbonate (Tums) along with high-calcium foods (like milk or cheese), you can end up with dangerously high calcium levels in your blood. This can lead to kidney stones or even kidney failure.

🔗 Read more: What's the Average Resting Heart Beat and Why Your Number Might Be Lying to You

Dr. M. Michael Wolfe, a gastroenterologist and professor, has often pointed out that while these meds are safe for occasional use, the "over-the-counter" status gives people a false sense of total security. Your kidneys have to filter all those minerals. If you’re overdoing it, you’re putting a load on your system that it wasn't designed to handle 24/7.

When the Burn Means Something Else

Here is the scary part. Heartburn and heart attacks can feel remarkably similar.

The vagus nerve serves both the heart and the esophagus. Sometimes the brain gets the signals crossed. Every year, people show up in ERs thinking they’re having a heart attack when it’s just a bad reaction to a spicy taco. But the reverse happens too. People sit on their couch chewing Tums while they’re actually experiencing cardiac distress.

If your "heartburn" comes with shortness of breath, sweating, or pain radiating into your jaw or left arm, put the antacids down and call 911.

Beyond that, chronic acid reflux can lead to Barrett’s Esophagus. This is a condition where the lining of your esophagus changes to look more like the lining of your intestine because it’s trying to protect itself from the constant acid bath. It’s a precursor to esophageal cancer. If you’re using antacids more than twice a week for several weeks, you need to see a doctor, not a pharmacist.

Better Ways to Manage the Fire

So, how do you handle this without becoming dependent on the chalky tablets?

First, look at the mechanics. Gravity is your friend. If you get reflux at night, stop eating three hours before bed. When you lie down with a full stomach, you’re basically asking the acid to leak out. Propping up the head of your bed (using blocks under the bed frame, not just extra pillows which can kink your torso and make it worse) can keep the acid where it belongs.

Second, watch the triggers. It’s not just "acidic" foods like lemons. It’s things that relax the lower esophageal sphincter.

👉 See also: Can Takis Cause Ulcers? What Most People Get Wrong About Spicy Snacks

- Caffeine

- Chocolate (sorry)

- Peppermint

- Alcohol

- Nicotine

These all tell that little valve to relax, which is exactly what you don't want.

Also, consider your weight. Extra pounds, especially around the midsection, put physical pressure on your stomach (intrathoracic pressure). It’s like squeezing a tube of toothpaste with the cap off. Even a modest weight loss can significantly reduce how often you need to ask "how do antacids work" because you simply won't need them as much.

Actionable Steps for Heartburn Relief

If you’re currently dealing with the burn, don't just mindlessly swallow pills. Use a strategic approach to get relief without the side effects.

- Identify the Need: If it’s a sudden, occasional burn, go for a liquid antacid. Liquids coat the esophagus and work faster than tablets that have to be broken down by your stomach first.

- Check the Active Ingredient: If you’re prone to constipation, avoid aluminum-only brands. If you have a sensitive stomach, look for a calcium carbonate and magnesium mix.

- Time Your Meds: If you take other daily prescriptions, take your antacid at least 2 hours before or 4 hours after your other medications to avoid absorption issues.

- Log Your Triggers: Keep a simple note on your phone. Did it happen after a fatty meal? After a beer? Identifying the "why" is more important than treating the "how."

- Set a Limit: If you are reaching for antacids more than 14 days in a month, stop. Schedule an appointment with a gastroenterologist to rule out hiatal hernias or H. pylori infections.

Antacids are a brilliant tool of modern chemistry. They provide nearly instant relief by turning a painful chemical reaction into a harmless one. But they are a bandage, not a cure. Understanding the mechanics of your own digestion is the best way to keep the fire at bay for good.