You’re standing in a field, looking up at a giant, fluffy white mass that looks like it weighs nothing at all. It’s a trick. That cloud probably weighs over a million pounds. It’s basically a massive lake floating over your head, and if you've ever wondered how did clouds form in the first place, the answer is a lot more chaotic than your third-grade science textbook led you to believe. It isn't just "water goes up, water comes down." It’s a violent, microscopic battle between temperature, pressure, and—honestly, the weirdest part—floating bits of dust, sea salt, and even bacteria.

Without those tiny "seeds," we wouldn’t have clouds. The sky would just be a humid, transparent mess.

💡 You might also like: Job Letter for Teacher: Why Your Cover Letter is Actually Getting Ignored

The Recipe for a Floating Ocean

Basically, you need three things. You need moisture, you need a drop in temperature, and you need something for the water to grab onto. Think of it like a crowded bar. If everyone is just standing around, nothing happens. But the moment you put a bowl of free peanuts on the counter, people cluster. In the atmosphere, those "peanuts" are aerosols.

When the sun beats down on the ocean or a damp forest, it kicks water molecules into a frenzy. They turn into gas. This water vapor is invisible, which is why you can’t see the "trail" of a cloud forming until it’s already happened. But as that warm air rises—because warm air is less dense and basically wants to escape the surface—it starts to hit lower pressure.

Here’s the thing: as air rises, it expands. As it expands, it cools. This is a fundamental law of thermodynamics. You’ve felt this if you’ve ever let air out of a tire; the valve gets cold. Once that air reaches a specific temperature known as the dew point, it can’t hold all that water vapor anymore. The air is "saturated."

The Secret Ingredient: Cloud Condensation Nuclei

This is where most people get the story wrong. Water doesn’t just magically turn into a droplet the second it gets cold. If the air were perfectly clean, you’d need the humidity to reach something like 400% before a droplet would form on its own. That doesn’t happen in nature. Instead, the water looks for a "cheat code."

These are called Cloud Condensation Nuclei (CCN). We’re talking about microscopic specks of:

- Volcanic ash

- Smoke from forest fires

- Salt spray from the ocean

- Clay and desert dust

- Even organic matter like pollen or fungal spores

NASA has actually done extensive research on how these aerosols dictate whether a cloud is "bright" (reflecting more sunlight) or "dark" (filled with rain). When the water vapor hits these particles, it flashes into a liquid or ice crystal. Boom. You have a cloud.

Why Do They Look So Different?

If the process is always the same, why isn't every cloud just a big blob? It’s all about the "lift."

✨ Don't miss: The Blue Glass Lamp Base: Why This One Piece Makes Your Whole Room Work

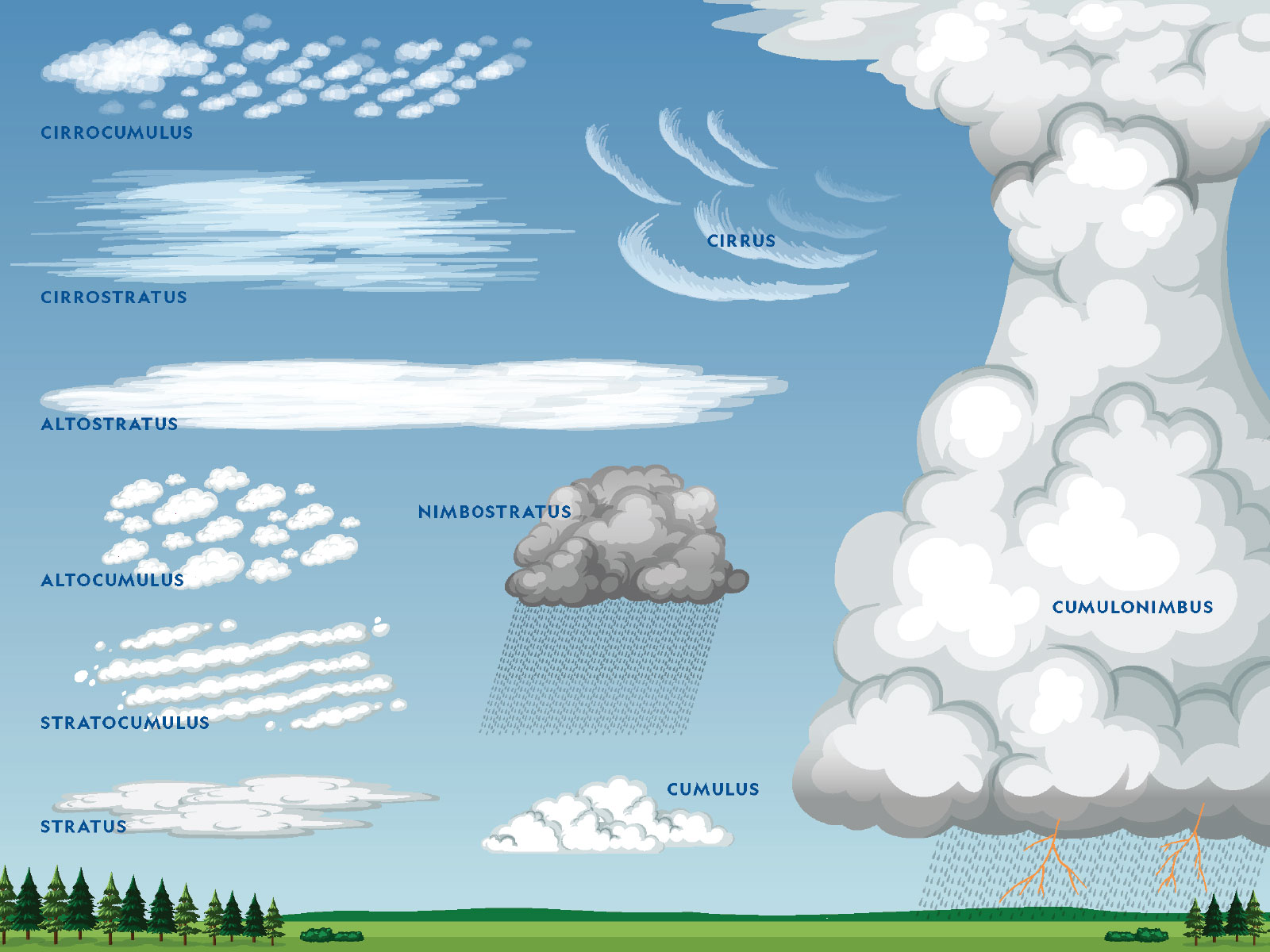

How did clouds form into those tall, scary anvils you see before a thunderstorm? That’s convection. The ground gets super hot, sends a "bubble" of warm air screaming upward, and it doesn't stop until it hits the top of the troposphere. These are Cumulonimbus. They are high-energy, high-drama clouds.

Then you have frontal lifting. This is when a big mass of cold air acts like a snowplow, shoving warm air out of the way and forcing it upward. This usually creates those flat, gray blankets called Stratus clouds that make you want to stay in bed and drink tea all day.

Then there’s the "mountain effect," or orographic lift. If you've ever lived in a place like Seattle or near the Rockies, you know this well. The wind hits a mountain, has nowhere to go but up, cools down, and dumps all its water on the windward side. By the time the air gets to the other side, it's dry. That’s why you get lush forests on one side of a mountain and a desert on the other.

The Surprising Role of Biology

We used to think clouds were purely a chemistry and physics game. We were wrong. Recent studies, including work published in Nature Communications, suggest that marine microbes play a massive role.

Phytoplankton in the ocean release a gas called dimethyl sulfide (DMS). Once it hits the air, it reacts to form sulfuric acid, which clumps together to create—you guessed it—seeds for clouds. So, in a very real way, the life in our oceans is actively engineering the weather above them to stay cool. It’s a feedback loop that feels almost like the planet is breathing.

Ice vs. Water

Not all clouds are liquid. High-altitude clouds, like those wispy Cirrus clouds that look like horse tails, are made entirely of ice.

At 30,000 feet, it’s freezing. But water is weird—it can actually stay liquid way below freezing (supercooled) if it doesn't have a specific type of seed to freeze around. Usually, it takes a specific shape of dust or even a certain type of bacteria (like Pseudomonas syringae) to trigger the transition from "supercooled liquid" to "ice crystal." This is actually how "cloud seeding" works; humans fly planes into clouds and dump silver iodide to trick the water into freezing and falling as snow or rain.

The Human Impact on the Sky

We are changing how clouds form. It's not just a "climate change" buzzword; it's a physical reality of our industrial output.

When we burn fossil fuels, we aren't just adding CO2; we’re adding a massive amount of extra aerosols. More "seeds" mean the water vapor is spread out over more particles. Instead of a few big droplets that fall as rain, you get millions of tiny droplets that stay suspended. This makes clouds look whiter and stay around longer. While that sounds like it might cool the planet (by reflecting sun), it also messes with rainfall patterns, leading to droughts in places that actually need the water.

🔗 Read more: Your Amazon Com Gift Card Balance: How to Find It and Why It Disappears

What You Can Do With This Knowledge

Understanding how did clouds form isn't just for trivia night. It changes how you see a storm rolling in. If you see clouds starting to build vertically like towers, the "updraft" is strong, and you should probably find cover. If you see high-altitude "mares' tails" (Cirrus), a change in the weather is usually about 24 to 48 hours away.

Next Steps for the Weather-Curious:

- Get a "Cloud Key": Download a basic identification chart from the NOAA website. Being able to tell a Cirrocumulus from an Altocumulus helps you predict your own local afternoon weather without an app.

- Watch the "Base": Next time you see a flat-bottomed cloud, realize you are looking at the exact altitude where the temperature dropped to the dew point. That flat line is a physical boundary in the sky.

- Observe "Virga": Look for clouds with "streaks" coming down that don't hit the ground. That’s rain evaporating before it reaches you because the air underneath is too dry.

- Check Local Aerosol Levels: Use an Air Quality Index (AQI) app. High pollution days often lead to "hazy" cloud formations rather than crisp, defined ones because there are too many condensation nuclei competing for water.

Clouds are the visible evidence of the invisible work the atmosphere is doing to move heat around the planet. They aren't just "there." They are a constant, shifting result of a complex dance between the ocean, the dirt, and the sun.