If you’ve ever spent a late night staring at a digital map of your own city, wondering where the "ground zero" circle would actually end, you aren't alone. It is a morbid curiosity. We see the headlines about global tensions and naturally, we want to know: How big is it, really? Visualizing destruction is hard. Numbers like "kilotons" or "megatons" feel abstract, almost like video game stats. But when you overlay those numbers onto a nuclear bomb size map, the abstraction vanishes. Suddenly, the blast radius isn't just a number; it’s your childhood school, your favorite coffee shop, and the bridge you cross every morning.

The scale of these weapons is honestly hard to wrap your head around without these visual aids. From the "Little Boy" dropped on Hiroshima to the monstrous Tsar Bomba, the jump in power isn't linear—it's exponential. Let's get into the weeds of how these maps work and what the different sizes actually mean for the real world.

The Science Behind the Nuclear Bomb Size Map

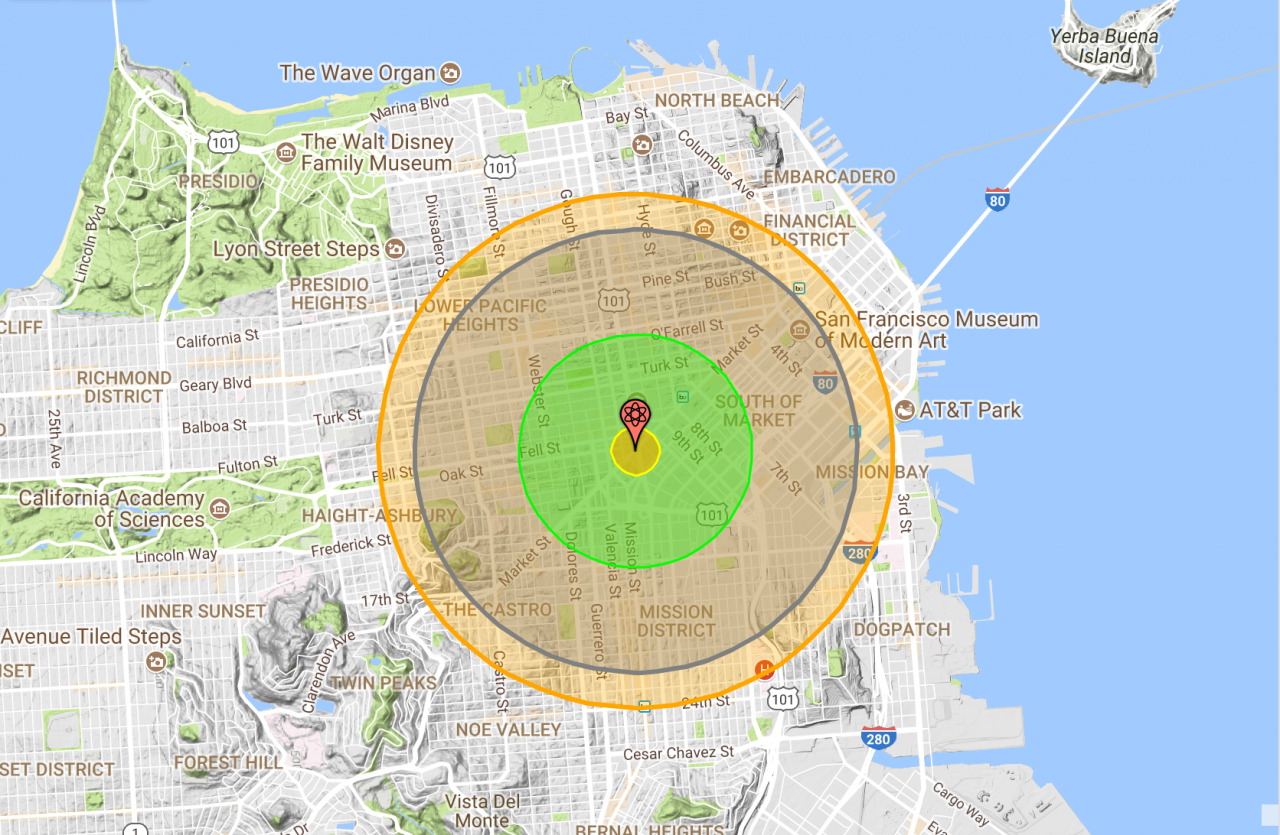

Most people think a nuclear explosion is just one big firey circle. It's not. It's actually a series of overlapping physical effects. When you look at a simulator like Alex Wellerstein’s NUKEMAP—which is basically the gold standard for this stuff—you’re seeing different zones of intensity.

First, there's the fireball. This is the literal center of the sun appearing on Earth for a split second. Inside this circle, everything is vaporized. Gone.

Then you have the heavy blast damage radius. This is where the shockwave—a wall of compressed air—is so strong it knocks down concrete buildings. If you're in this circle, your house isn't just damaged; it’s flattened. Further out, you get the thermal radiation ring. This is arguably the most terrifying part because it extends the furthest. It’s the heat that causes third-degree burns to anyone caught in the open.

The size of these rings depends entirely on the "yield" of the weapon.

Yield is measured in TNT equivalent. A 15-kiloton bomb (like Hiroshima) is tiny compared to a modern W88 warhead. We’re talking about the difference between a firecracker and a bonfire. Most modern nuclear bomb size map tools allow you to toggle between "airburst" and "surface burst." This matters. An airburst spreads the blast further, maximizing the area of destruction, while a surface burst kicks up more dirt, creating lethal radioactive fallout that drifts with the wind for hundreds of miles.

Comparing the "Small" Ones to the Modern Monsters

It is a common misconception that all nukes are roughly the same size. They really aren't.

The Hiroshima Benchmark

The "Little Boy" bomb had a yield of about 15 kilotons. On a map of a city like New York or London, the 5-psi blast radius (where most residential buildings collapse) only covers a few blocks. It’s devastating, but it’s localized.

The Modern Warhead (W88 or Topol)

Most modern strategic warheads are in the 300 to 800 kiloton range. This is where things get scary. If you drop an 800-kiloton warhead on a map, the thermal radiation ring—the area where people get severe burns—can stretch for over 6 miles in every direction. That’s a 12-mile wide circle of fire.

The Tsar Bomba: The Outlier

Then there’s the Soviet Tsar Bomba. It was tested at 50 megatons. That is 50,000 kilotons. If you put that on a nuclear bomb size map, the "total destruction" zone alone covers entire metropolitan areas. The heat from that blast would cause burns nearly 40 miles away. It’s so large it’s actually impractical as a weapon; the plane that dropped it barely escaped the shockwave even after flying miles away.

Why Maps Use Different Colors and What They Mean

When you're looking at a map visualization, the colors aren't just for show. They represent specific thresholds of physics.

- Yellow/Orange Center: The fireball. 100% fatality rate.

- Red Ring: Heavy blast damage. 20 psi of pressure. Even reinforced concrete structures are heavily damaged or destroyed.

- Green/Gray Ring: Moderate blast damage. 5 psi. Most residential buildings collapse. Widespread fatalities.

- Orange Outer Ring: Thermal radiation. This is where the heat is intense enough to ignite skin and flammable materials like wood or paper.

- The "Plume" (The elongated tail): This is the fallout. It isn't a circle because it follows the wind. It represents the radioactive dust that falls back to earth.

The fallout is the "invisible killer." While the blast happens in seconds, the fallout can make land uninhabitable for weeks or months. On a nuclear bomb size map, you can see how a bomb dropped on Washington D.C. could realistically send lethal radiation all the way to Philadelphia or New York depending on which way the wind is blowing that day. It’s a sobering reminder that nuclear effects aren't contained by city limits.

The Limitations of Simulators

Maps are great for a general idea, but they have limits. They usually assume "flat terrain."

If you live in a city with lots of hills, like San Francisco or Pittsburgh, the geography actually changes the blast wave. Hills can "shadow" certain areas from the direct heat of the fireball, but they can also funnel the shockwave through valleys, making it more intense in certain spots.

Buildings also matter. In a dense urban core like Manhattan, the "canyon effect" of skyscrapers can bounce the shockwave around. Simulators struggle to calculate that perfectly. Most nuclear bomb size map tools use the Mills-Peterson or similar mathematical models which are incredibly accurate for general planning, but they can't account for your specific basement's structural integrity.

What People Get Wrong About Survival Zones

There’s this idea that if you’re "on the map," you’re dead. That’s not necessarily true.

Even in the moderate damage zones, being inside a sturdy building—especially away from windows—dramatically increases survival chances. The "map" shows what happens to people caught in the open.

A major factor often ignored in casual browsing of a nuclear bomb size map is the "flash-to-bang" time. Light travels faster than sound. If you see the flash, you have seconds to get away from glass before the shockwave hits. Maps don't show the timing, just the final footprint.

Actionable Insights: How to Use This Information

Looking at a nuclear bomb size map shouldn't just be about doom-scrolling. It provides actual data that can inform basic preparedness.

- Identify Your Zone: Use a tool like NUKEMAP to see where your home and workplace fall relative to likely targets (usually government centers or major infrastructure). If you’re in the thermal radiation zone but outside the heavy blast zone, your primary concern is fire and flash protection.

- Know the Wind: Check the prevailing winds in your area. Fallout travels downwind. Knowing which way the air usually moves tells you which direction you’d need to move—or which way you should not go.

- The "Two-Week" Rule: Most radioactive fallout loses about 90% of its intensity in the first 48 hours, and 99% after two weeks. If a map shows you in a fallout plume, the goal isn't necessarily to run—it's to stay inside a "heavy" structure (basement, center of a brick building) for those first 14 days.

- Avoid Windows: Looking at the map proves that the blast radius is massive. If you ever see a flash that is brighter than the sun, do not look at it and do not go to the window to see what happened. The shockwave is coming. Drop to the floor immediately.

The reality of nuclear weapons is grim, but the data provided by a nuclear bomb size map is one of the few ways we can translate "megatons" into something our human brains can actually process. It moves the conversation from "scary myths" to "measurable physics." Understanding the footprint of these weapons is the first step in understanding the sheer scale of the risk—and the importance of the diplomacy that keeps these circles off our actual maps.

✨ Don't miss: Newton's Cooling Law Calculator: Why Your Coffee Coldness Is Actually Predictable

Key Data Points for Reference

| Weapon Name | Yield | Heat Radius (3rd Degree Burns) |

|---|---|---|

| Davy Crockett | 20 Tons | ~0.1 miles |

| Little Boy (Hiroshima) | 15 Kilotons | ~1.1 miles |

| W87 (Minuteman III) | 300 Kilotons | ~5.0 miles |

| B83 (Largest in US Arsenal) | 1.2 Megatons | ~8.2 miles |

| Tsar Bomba (Tested) | 50 Megatons | ~37.3 miles |

To get the most accurate picture of your specific risk, consult the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) guidelines on nuclear "hazards and zones." They provide detailed breakdowns of sheltering-in-place versus evacuation, which are often counter-intuitive. For instance, leaving your home during a fallout event can be more dangerous than staying in a poorly insulated basement. Stay informed, use the mapping tools to understand the geography of your area, and focus on the practical physics of protection rather than the sensationalism of the "end of the world."

The best way to use these maps is to recognize that distance is your friend, but density is your shield. Concrete, brick, and earth are the only things that effectively mitigate the rings of destruction shown on a nuclear bomb size map. Focus on identifying the sturdiest structures in your daily orbit. Knowledge of the blast footprint isn't just about fear; it's about knowing where the safety margins begin.