History isn't just dates. It's dirt. When you look at a hundred years war map, you aren't looking at a static border like the one between Kansas and Nebraska. You’re looking at a moving, breathing disaster area that spanned from 1337 to 1453. It’s basically a 116-year game of tug-of-war where the rope is made of people, castles, and a whole lot of spite. Honestly, if you try to find one "official" map of this conflict, you're going to get frustrated because the borders changed faster than a medieval peasant could harvest wheat.

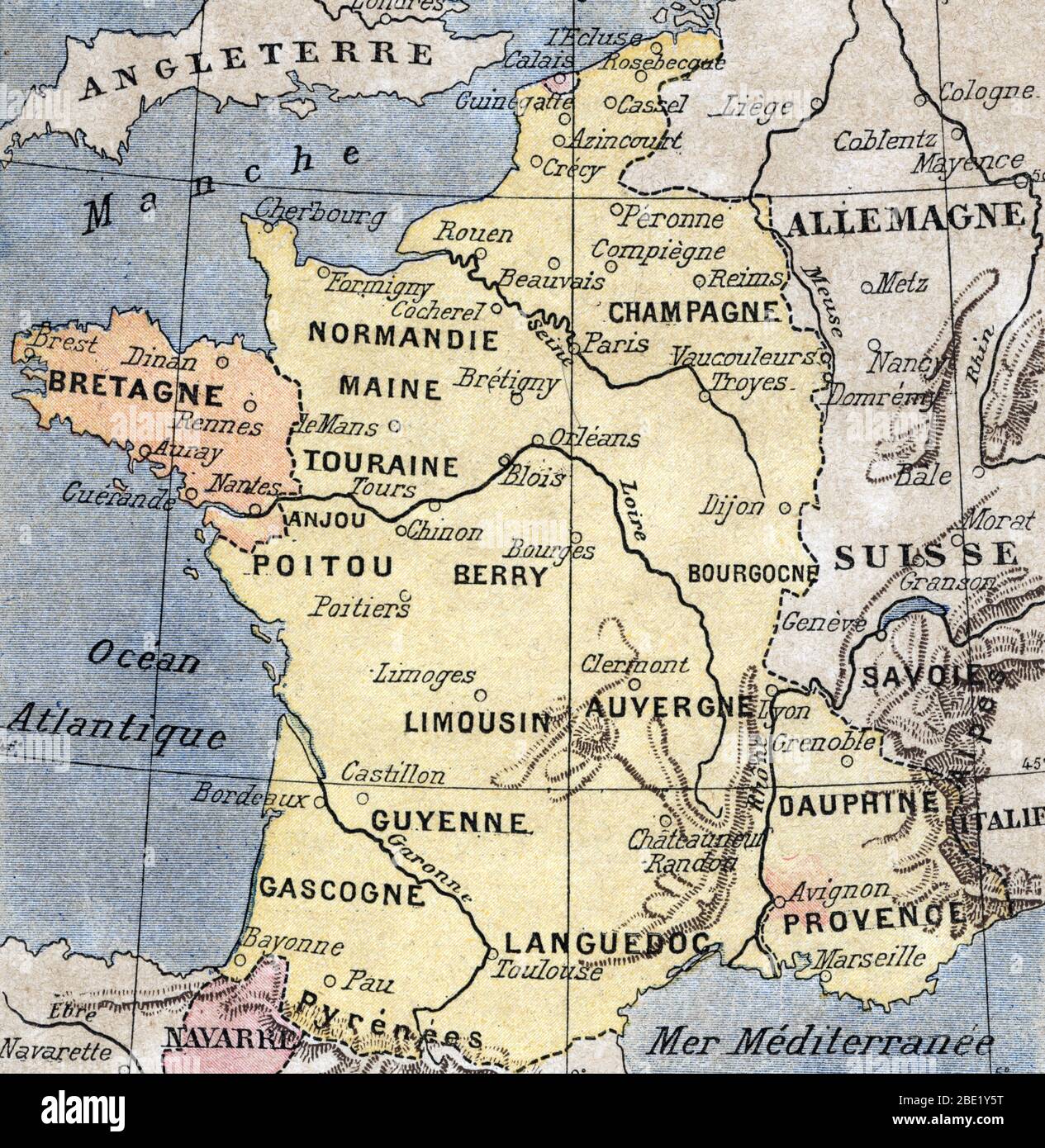

Edward III started the whole mess. He thought he owned France. Philip VI disagreed. What followed was a century of "chevauchées"—which is just a fancy French word for riding through the countryside and burning everything you see—and some of the most lopsided battles in human history. To understand the map, you have to understand that "France" didn't really exist as a unified country back then. It was a patchwork of duchies, counties, and territories held by lords who liked to flip-flop their loyalties whenever the wind blew south.

The 1337 Starting Line: A Continental Identity Crisis

Look at a map of France at the start of the 14th century. It’s a mess. The English King actually held a massive chunk of southwest France called Gascony. Imagine if the Governor of New York also happened to own most of Florida, but had to pay taxes to the President for it, while also claiming he was the President. That’s the level of awkward we're talking about.

This region, Gascony, was the engine of the English economy. It produced wine. Tons of it. The English loved wine, and the French king, Philip VI, wanted the tax revenue from that wine. When he tried to "confiscate" the Duchy of Aquitaine, Edward III didn't just send a sternly worded letter. He claimed the French throne through his mother, Isabella. If you’re tracking this on a hundred years war map, you’ll see the English influence concentrated in two spots: the northern coast near Calais (eventually) and the deep southwest.

Why the Map Keeps Changing During the Edwardian Phase

The early years were a disaster for the French. Crecy. Poitiers. These aren't just names; they are the moments when the map practically turned English overnight. At the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, the English actually captured the French King, John II. Imagine the chaos.

When the Treaty of Brétigny was signed in 1360, the hundred years war map looked like England had won the lottery. They gained full sovereignty over a massive chunk of the west and southwest. They didn't have to pay homage to the French king anymore. For a brief moment, it looked like "Greater England" was a permanent fixture of the European continent. But geography is a cruel mistress. Holding that much land requires a lot of soldiers, and England just didn't have the population to keep every castle garrisoned against a pissed-off local population.

💡 You might also like: Wingate by Wyndham Columbia: What Most People Get Wrong

The Burgundy Factor: The Third Player No One Mentions

You can't talk about a map of this war without talking about Burgundy. This is where most people get the history wrong. They think it was just England vs. France. It wasn't. It was England vs. France... and Burgundy was the chaotic neutral character in the corner.

The Dukes of Burgundy were technically French vassals, but they wanted to build their own empire. They controlled parts of what we now call the Netherlands and Belgium, plus a huge chunk of eastern France. For a long time, they sided with the English. If you see a hundred years war map from around 1420, you'll see a massive "Burgundian" block that effectively cut the French resistance in half. This alliance is what allowed Henry V to march into Paris. Yes, the English actually held Paris. It’s easy to forget that.

Agincourt and the Peak of English Power

- Mud. Longbows. Henry V.

The Battle of Agincourt is the climax of every Shakespeare play, but its impact on the physical map was even more dramatic. By 1420, the Treaty of Troyes recognized Henry V as the heir to the French throne. If you look at a map from this specific year, Northern France is almost entirely red (English). The "true" French heir, the Dauphin Charles, was kicked out of Paris and forced to hide in the south, mocked as the "King of Bourges."

The English weren't just raiding anymore; they were colonizing. They were handing out French estates to English knights. This wasn't a war of borders; it was a war of extinction for the French state.

Joan of Arc and the Great Reversal

Everything changed because of a teenage girl from Lorraine. Joan of Arc didn't just win battles; she changed the map's psychology. Before her, the French were losing everywhere. After she broke the Siege of Orléans in 1429, the momentum shifted.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: The Sky Harbor Airport Map Terminal 3 Breakdown

Orléans is the "key" to the hundred years war map. It sits right on the Loire River. If the English had taken it, they could have pushed into the south and finished the Dauphin off. They didn't. Joan’s victory allowed Charles VII to march through enemy-held territory to Reims to be crowned. That march is a weird, long line on the map that makes no sense militarily, but it made all the sense in the world politically. It proved he was the "real" king.

The Slow Death of English France

After Joan was burned, the English didn't just disappear. It took another twenty years. But the map tells the story of a slow, grinding retreat.

- 1435: The Congress of Arras. This is the big one. Burgundy finally ditched the English and rejoined the French. Suddenly, the English were alone.

- 1436: The French took back Paris.

- 1450: The Battle of Formigny. The French used cannons—real, primitive artillery—to blast the English off the field in Normandy.

- 1453: The Battle of Castillon. This is the official end. No more English army in France, except for a tiny, tiny dot at Calais.

How to Read a Hundred Years War Map Today

If you go to France today, you can still see the "map" in the architecture. In the southwest, specifically the Dordogne region, there are "bastides"—fortified new towns built by both the English and the French to claim territory. They are laid out in grids. You can literally walk through the physical remains of the war's borders.

The map also explains why the English language is such a weird hybrid. For 300 years, the ruling class of England spoke French. The war forced them to pick an identity. By the end of it, the English were English, and the French were French. The lines on the map became real borders, not just property disputes between cousins.

Practical Steps for History Buffs and Travelers

If you actually want to see where the hundred years war map comes to life, don't just look at a book. Go to the sites.

👉 See also: Why an Escape Room Stroudsburg PA Trip is the Best Way to Test Your Friendships

First, visit Calais. It was the last English stronghold, held until 1558. You can still feel the "gateway" nature of the city. Then, head to the Castle of Castillon near Bordeaux. There's a massive reenactment there every summer that involves hundreds of actors and horses. It's the best way to see how the final collapse of the English "map" actually looked.

Also, check out the Chronicles of Jean Froissart. He was a contemporary writer who traveled through these territories while the war was happening. His descriptions of the landscape give a "boots on the ground" feel that a 2D map just can't provide.

The most important thing to remember is that the map was never finished. The English kings kept the French lilies on their coat of arms until 1801. They didn't want to admit the map had changed. But by 1453, the modern shape of Europe was already set. France was a kingdom, England was an island, and the messy, overlapping duchies of the Middle Ages were gone for good.

To dig deeper into the specific troop movements, look for "The Hundred Years War" by Jonathan Sumption. It's a multi-volume beast, but it’s the gold standard. If you want a quicker visual, the "Historical Atlas of France" provides the best overlays of how the borders shifted decade by decade. Stop looking for one map. Look for the transition. That's where the real history is hidden.

Next Steps:

Research the Battle of Castillon specifically to understand how gunpowder finally rendered the traditional English longbow—and their territorial claims—obsolete. If you're planning a trip, map out a route through the Périgord region to see the bastide towns; they are the most preserved "living maps" of the 14th-century borderlands.