Space is mostly empty, quiet, and honestly, a bit boring until something goes wrong. When a star wanders too close to a supermassive black hole, the result isn't just a simple "gulp." It’s a messy, violent, and incredibly bright cosmic murder known to astronomers as a Tidal Disruption Event, or TDE.

Basically, the black hole doesn't just pull the star in. It shreds it.

Gravity is a Harvester

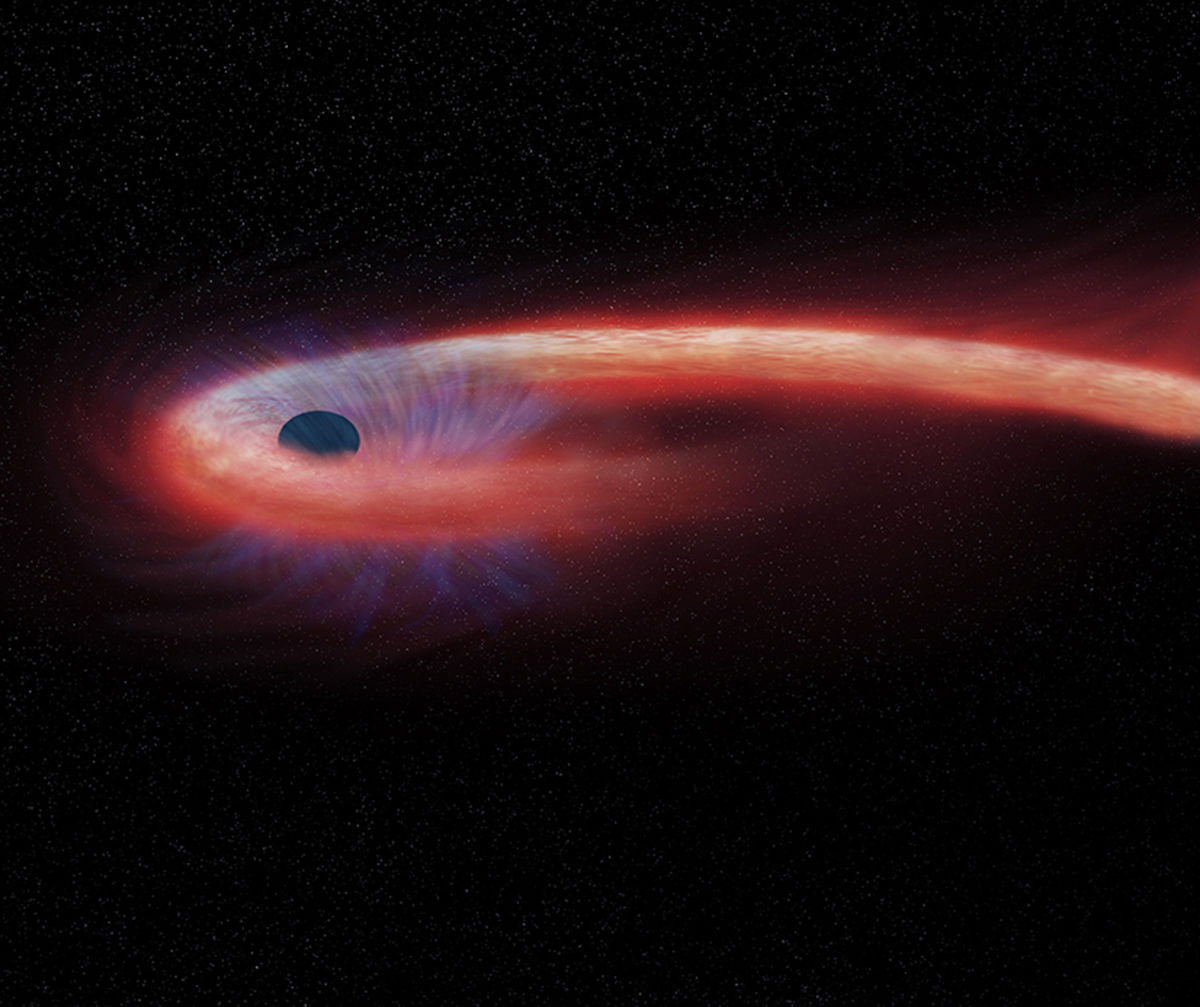

Imagine a rubber band being pulled from both ends. Now imagine that rubber band is a sphere of burning gas a million miles wide. As a star approaches the event horizon, the gravitational pull on the side of the star facing the black hole becomes exponentially stronger than the pull on the far side. Scientists call this "spaghettification." It’s a weird word for a terrifying process. The star gets stretched into a long, thin noodle of plasma.

Most people think of black holes as cosmic vacuum cleaners. They aren't. They are more like messy toddlers with a plate of spaghetti. A black hole eats a star with very little grace, and a huge portion of the star's guts actually gets flung back out into space at relativistic speeds.

The Flash That Gives It Away

How do we even know this is happening? Black holes are, by definition, dark. But when a black hole eats a star, the friction and gravity heat that stellar debris to millions of degrees. It glows.

These flashes are some of the brightest events in the known universe. In 2019, the TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) caught a TDE in a galaxy 375 million light-years away. It was named ASASSN-19bt. Astronomers watched it in real-time. It wasn't a quick blink; the "meal" lasted months as the black hole slowly wound the shredded gas around itself in an accretion disk.

The light emitted is usually in the ultraviolet and X-ray spectrum. This is why NASA’s Swift mission and the Chandra X-ray Observatory are so vital. They see the "scream" of the dying star that our human eyes would miss entirely.

Why Some Stars Survive (Sort Of)

Not every encounter ends in a total meal. Sometimes, it’s just a snack.

Researchers like Suvi Gezari at the Space Telescope Science Institute have documented cases where a star survives a "partial" tidal disruption. These are "zombie stars." They get close enough to lose their outer layers—basically getting their skin peeled off by gravity—but they have enough velocity to escape the black hole’s ultimate grip. They fly away, lighter and weirder than they were before.

There is also the "eccentric" meal. Sometimes the star’s orbit is so elongated that the black hole takes a bite every few years. Every time the star reaches its closest point (periapsis), the black hole siphons off more gas. It’s a slow-motion execution that can last for centuries.

✨ Don't miss: Remembering the way back 2010: When the Internet Finally Got Real

The "Belch" After the Meal

One of the most surprising discoveries in the last decade is that black holes have a "delayed belch."

In 2022, a team led by Cady Coleman and other researchers noticed something strange about a TDE they had been tracking. Years after the black hole had finished eating the star, it suddenly started emitting radio waves. It was as if the black hole was regurgitating material it had swallowed years prior.

This challenges the "Infall" model. It suggests that the physics of how matter settles into a black hole is far more complex than a simple downward spiral. Some of that energy is stored and then ejected in powerful jets long after the initial feast is over.

Misconceptions About the Event Horizon

You’ve probably seen Interstellar. You might think a star just disappears once it crosses the event horizon.

Actually, for a supermassive black hole, the tidal forces might be weak enough at the event horizon that a star could cross it "whole" before being torn apart. But for smaller, stellar-mass black holes, the "spaghettification" happens long before the star ever touches the point of no return.

It’s all about the gradient.

If the black hole is massive enough—billions of times the mass of our sun—the "pull" is more uniform. If it’s a "small" black hole, the difference in gravity between your head and your toes (or a star's poles) is so vast that you’re ripped apart instantly.

Why This Matters for Us

Earth is safe. The nearest supermassive black hole is Sagittarius A*, located at the center of the Milky Way. It’s about 26,000 light-years away. While it does eat the occasional gas cloud or stray star, we are far enough out in the "suburbs" of the galaxy to avoid the chaos.

However, studying these events helps us calculate the "spin" of black holes. By measuring the temperature and speed of the glowing gas as the black hole eats a star, physicists can determine how fast the black hole is rotating. This is fundamental to proving Einstein’s General Relativity.

Actionable Steps for Amateur Astronomers

You can’t see a TDE with a backyard telescope. They are too far away and require specialized sensors. But you can stay involved in the hunt.

- Follow the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF): This project scans the entire Northern sky every two days. They are the primary "alarm system" for TDEs.

- Use the "NASA Eyes" App: It’s a free tool that lets you visualize where these events are happening in relation to our solar system.

- Contribute to Citizen Science: Platforms like Zooniverse often have projects where regular people help sort through telescope data to find "transients"—light sources that appear out of nowhere. You might be the first to see a star being eaten.

- Monitor the Astronomer’s Telegram (ATel): This is where professional astronomers post real-time alerts. If you see a post about a "luminous transient in a galactic nucleus," you’re looking at a black hole having lunch.

The universe is violent, but that violence is exactly how we map the dark parts of the map. Without these doomed stars, black holes would remain almost entirely invisible.