It’s hard to remember what watching TV felt like back in 2013. We were still slaves to the weekly schedule, mostly. Then came Frank Underwood. When Netflix dropped the entire first season of House of Cards at once, it didn’t just give us a dark political thriller; it basically blew up the blueprint for how we consume stories. It was a gamble. A massive, $100 million gamble on two seasons before a single frame had even aired.

The show felt different. It was cold. It was sleek. David Fincher’s fingerprints were everywhere—that muted color palette, the clinical camera movements, and the feeling that something terrible was always happening just off-screen. Honestly, it changed everything. Without this specific House of Cards, we probably don't get the "prestige" streaming era as we know it today.

The Algorithm That Predicted a Hit

People like to talk about "the algorithm" today like it's some kind of spooky ghost in the machine, but for Netflix in the early 2010s, it was just smart business. They looked at the data. They saw people loved the original UK 1990s version of House of Cards. They saw those same people were obsessed with David Fincher’s movies. They noticed a huge overlap with fans of Kevin Spacey.

It wasn't a guess.

By combining those three specific data points, Netflix realized they had a guaranteed audience before they even hired a writer. Ted Sarandos, who was then the Chief Content Officer, famously bypassed the "pilot" process. Usually, a network orders one episode, tests it, hates it, and tweaks it until it’s bland. Netflix just said, "Here’s the money for twenty-six episodes. Go play." That level of creative freedom was unheard of at the time. It shifted the power from the networks to the creators, and eventually, to us—the viewers who wanted to watch ten hours of television on a rainy Saturday without moving from the couch.

Breaking the Fourth Wall

One of the most polarizing things about the show was Frank Underwood’s habit of looking directly at us. It’s a technique called breaking the fourth wall. In the original British series, Ian Richardson’s Francis Urquhart did it with a Shakespearean wink. In the American House of Cards, it felt more like being recruited into a conspiracy.

When Frank looks at the camera and explains how "generosity is its own form of power," he’s not just talking to himself. He’s making us his accomplices. You’re sitting there in your pajamas, and suddenly the most powerful man in D.C. is treating you like his only friend. It's seductive. It’s also deeply manipulative storytelling. It kept us hooked even when the plot got, let’s be real, a little ridiculous in the later seasons.

📖 Related: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

The Reality vs. The Fiction

Is D.C. actually like House of Cards?

If you ask people who actually work on Capitol Hill, they usually laugh. They’ll tell you that real politics is way more boring. It’s mostly meetings about milk subsidies and waiting for elevators. The show made it look like every hallway conversation was a life-or-death power play. It was "political opera" rather than a documentary.

- The Murder Aspect: In the show, Frank pushes people in front of trains. In real life, politicians just leak embarrassing emails to the Washington Post.

- The Efficiency: Frank Underwood gets things done. Real Congress? Not so much. The "Education Reform Act" in Season 1 would have taken a decade to pass in the real world, not a few weeks of clever arm-twisting.

- The Atmosphere: Everything in the show is gray, blue, and expensive. Real D.C. offices are often cramped, messy, and filled with lukewarm coffee in Styrofoam cups.

Still, the show captured a feeling of cynicism that resonated. It arrived right as public trust in institutions was cratering. It gave people a "behind the curtain" look that felt true, even if the details were heightened for drama.

Beau Willimon’s Vision

We can’t talk about the show without mentioning Beau Willimon. He was the showrunner for the first four seasons, and he brought a specific kind of grit to the writing. He’d actually worked in politics—interning for Chuck Schumer and working on campaigns for Hillary Clinton and Howard Dean. He knew the language. He knew how people in those rooms talked when the cameras weren't rolling.

When he left after Season 4, the show shifted. It felt different. Some fans argue it lost its groundedness and leaned too hard into the "crazy" twists. It’s a common problem with long-running series; how do you keep raising the stakes when your protagonist is already the President?

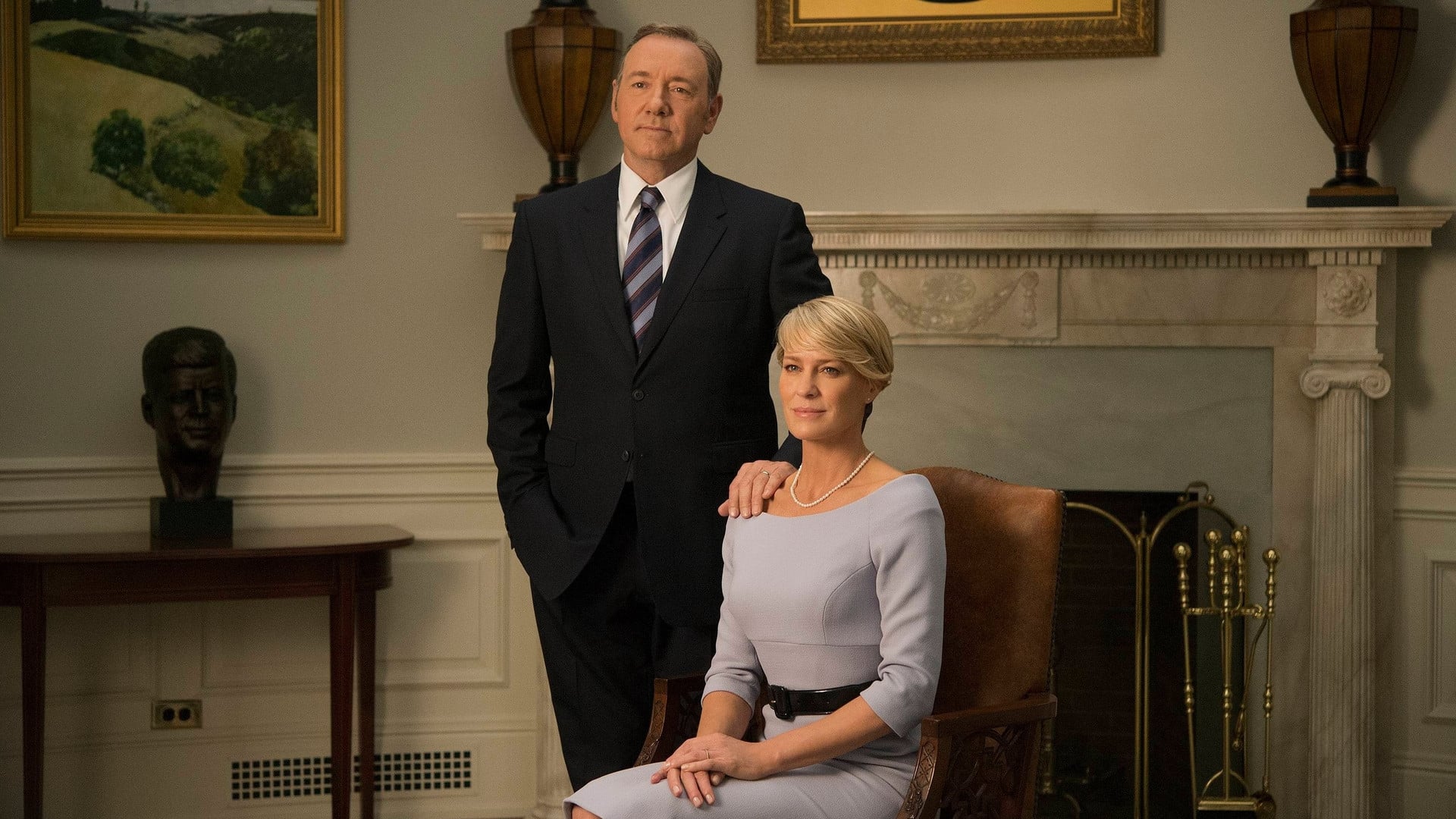

The Claire Underwood Evolution

For a long time, Claire was the "ice queen" in the background. But Robin Wright’s performance was so layered that she eventually became the true center of the show. Her style—those sharp suits and that cropped hair—became iconic. It was armor.

👉 See also: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

As the seasons progressed, the power dynamic shifted. It wasn't just Frank’s story anymore; it was about a marriage that was actually a business merger. They were two predators who realized they were stronger together than apart. Until they weren't. The "one chair" vs "two chairs" debate in the later seasons really highlighted the core conflict: can two people who both want everything ever actually share it?

Honestly, the way Robin Wright took over the lead role in the final season was a massive undertaking. The show had to be completely rewritten following the real-world scandals surrounding Kevin Spacey. It was a messy transition, and the final season is still a point of huge contention among fans. Some loved seeing Claire finally take the reins; others felt the show lost its soul without the Frank-Claire friction.

Why the Ending Still Stings

The final season was short—only eight episodes. It felt rushed. There was a lot of "tell, don't show" happening with Frank’s off-screen death. It’s a tough spot for any production to be in, but for a show that started with such precision, the ending felt a bit like a house of cards actually falling down.

There were so many plot threads left dangling. What happened to the Shepherd family? Did Doug Stamper ever really find peace? The ambiguity didn't feel intentional; it felt like a product of a show trying to survive a crisis. Yet, even with a rocky ending, the legacy of the first few seasons is untouchable.

Impact on the Industry

Before this show, "web series" were things you watched on YouTube for three minutes. House of Cards proved that the internet could produce better TV than TV could. It paved the way for Stranger Things, The Crown, and eventually the massive budgets of The Rings of Power.

It also changed how actors view streaming. Suddenly, A-list movie stars weren't afraid to do "TV" anymore because the "TV" was being directed by David Fincher and looked better than most movies in theaters. It started the "Gold Rush" of talent moving toward digital platforms.

✨ Don't miss: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

How to Revisit House of Cards Today

If you’re thinking about a rewatch, or if you’ve never seen it, there’s a way to do it that makes the most sense. Don’t just binge it all in a weekend. It’s too dark for that. You’ll end up feeling like the world is a terrible place.

The Best Way to Watch

- Stop after Season 2 (The "Perfect" Arc): If you want a tight, incredible story, the first two seasons are essentially a rise-to-power arc that concludes perfectly. It’s some of the best television ever made.

- Pay attention to the food: Sounds weird, but watch what Frank eats. The ribs at Freddy's represent his connection to his roots and his humanity. When he stops going there, he loses something.

- Watch the backgrounds: Fincher’s team spent a fortune on the sets. Every book on the shelf, every painting on the wall is there for a reason.

The show is a masterclass in tone. Even if you don't care about the politics, the way it uses sound and light is worth studying. It’s clinical. It’s precise. It’s a show about people who treat the world like a chessboard, and the cinematography reflects that by being just as calculated.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Creators

If you're looking to understand why this show worked or how to apply its lessons to your own media consumption or creation, keep these points in mind:

- The Power of First Impressions: The first scene of the series—Frank killing the dog—tells you exactly who he is and what the show is going to be. It’s a "litmus test" for the audience. If you can't handle that, you won't handle the rest.

- Data-Driven Creativity: Don't fear data. Netflix used it to give creators more freedom, not less. Use information to understand what people want, then give them a high-quality version of it they didn't expect.

- Characters Over Plot: We stayed for the political maneuvering, but we came back for the Underwoods. A great plot is nothing without characters people love to hate.

- Visual Consistency: Establishing a "look" for a project creates a world that feels immersive. Stick to a color palette and a style of movement to make your work recognizable.

Ultimately, House of Cards was the first of its kind. It was the "Big Bang" for the streaming world. While the ending was complicated and the real-world history of the show is messy, the art itself remains a fascinating study of power, marriage, and the lengths people will go to when they refuse to be "the bottom of the food chain."

The show taught us that "power is a lot like real estate. It's all about location, location, location." And for five years, the best location in the world of television was right there on our screens, watching the Underwoods tear D.C. apart.

For anyone looking to dive deeper into the world of political thrillers, start with the 1990 BBC original to see where the DNA came from, then watch the first two seasons of the Netflix version. You’ll see exactly how a classic story was updated for a new, more cynical generation. It's a lesson in adaptation that still hasn't been topped.

Check out the behind-the-scenes interviews with the production designers. Seeing how they built a fake White House in a warehouse in Maryland is almost as interesting as the show itself. It reminds you that television, like politics, is mostly about smoke and mirrors. But when the mirrors are this beautiful, you don't really mind being fooled.