If you spent any time on the weird side of the internet in the mid-2000s, you probably saw it. A grainy, pixelated image of a man’s corpse—real, not drawn—accompanied by the stark words Hong Kong 1997 game over. It wasn't a creepypasta. It wasn't a hoax. It was a real, playable game for the Super Famicom, and it might just be the most infamous piece of "kusoge" (crap game) ever programmed.

Honestly, the game is a mess. It’s a homebrew title developed in 1995 by Yoshihisa "Kowloon" Kurosawa, a Japanese gaming journalist who basically wanted to make the most offensive, lowest-quality product possible to mock the industry. He succeeded. But the reason we are still talking about it decades later isn't just the bad gameplay; it's the bizarre, nihilistic energy of that specific death screen and the political satire that felt like a fever dream.

The Story Behind the Infamy

Kurosawa didn't have a team. He didn't even really know how to code for the SNES properly. He ended up recruiting a friend who worked at an actual game company, and they cobbled the thing together over two days in a cramped apartment. The goal? Make something so bad it couldn't be ignored.

The premise is wild. You play as Chin (a digitized Bruce Lee from the film Game of Death), who is hired by the British government to wipe out the entire population of mainland China. Why? Because the 1997 handover was approaching, and the game’s "plot" suggests the influx of "fucking ugly reds" would lead to a crime wave. It’s intentionally provocative, xenophobic, and crude.

Kurosawa actually went to Hong Kong to find a street vendor who would help him distribute the game on floppy disks for the Nintendo "Magicom" (a copier device). He sold maybe 30 copies. That should have been the end of it. Instead, the internet happened.

📖 Related: The Problem With Roblox Bypassed Audios 2025: Why They Still Won't Go Away

Why the Hong Kong 1997 Game Over Screen Became a Legend

The most disturbing part of the game isn't the shooting. It’s what happens when you die. Instead of a "Try Again" or a cute animation, you are greeted with a low-resolution photograph of a man with a shattered skull and bloody injuries.

For years, people speculated about who the man was. Was it a real victim of the handover? Was it a developer?

The truth is much more mundane but still grim. It was a frame from a documentary about the Bosnian War or similar conflict—basically, Kurosawa just grabbed a shocking image from a video tape he had lying around. That specific Hong Kong 1997 game over screen became a rite of passage for early YouTube gamers like the Angry Video Game Nerd. It represented a time when the internet felt like the Wild West, where you could stumble upon something genuinely "cursed" without warning.

The Mechanics of a Disaster

The game plays like a broken version of Space Invaders or Galaga. You move Chin across the bottom of the screen and shoot projectiles at falling enemies.

👉 See also: All Might Crystals Echoes of Wisdom: Why This Quest Item Is Driving Zelda Fans Wild

- The Loop: A five-second loop of the Chinese children's song "I Love Beijing Tiananmen" plays constantly. It never stops. It will haunt your dreams.

- The Boss: Occasionally, the giant floating head of Tong Shau-ping (a misspelled Deng Xiaoping) appears as a final boss.

- The Difficulty: It is nearly impossible. One hit and you're done.

There is no nuance here. It’s a 16-bit protest against... well, everything. Kurosawa has since said in interviews with outlets like South China Morning Post that he’s surprised people still care. He finds the fascination with his two-day project hilarious and a bit baffling.

The Political Context You Might Have Missed

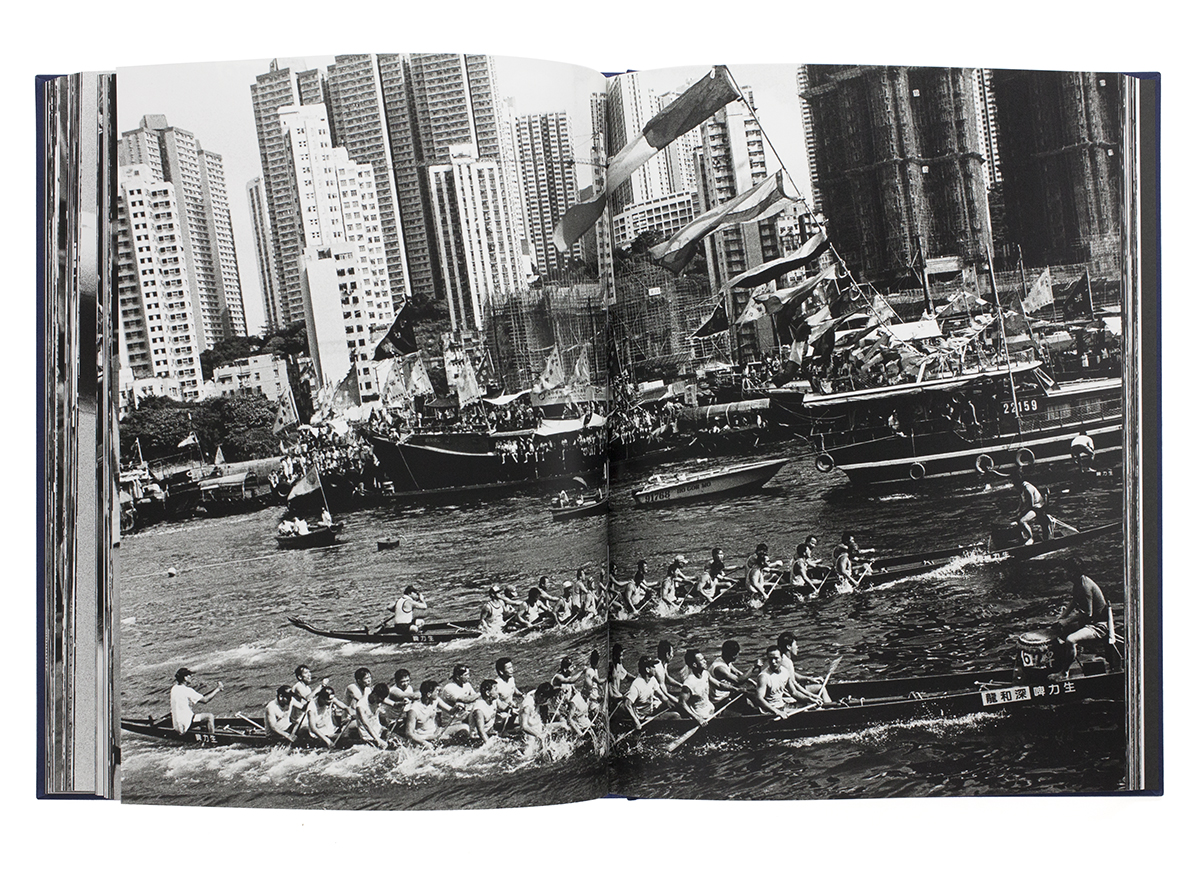

While the game is offensive and poorly made, it reflects a very real anxiety that existed in 1995. People in Hong Kong were genuinely terrified of what would happen when the British lease ended. There was a massive wave of emigration to Canada and the UK.

Kurosawa was tapping into that fear, albeit in the most tasteless way imaginable. He used the medium of a "kids' toy"—the Super Nintendo—to deliver a cynical, gory commentary on a major geopolitical event.

Most games from that era were polished, corporate products from Nintendo or Sega. Hong Kong 1997 was the antithesis. It was punk rock, if punk rock was poorly coded and featured stolen assets. It was one of the first truly viral "bad games" because it felt like it shouldn't exist. It felt illegal.

✨ Don't miss: The Combat Hatchet Helldivers 2 Dilemma: Is It Actually Better Than the G-50?

Is It Actually Playable Today?

If you're looking for a copy, good luck. Finding an original floppy disk is like finding a needle in a haystack made of gold. However, the ROM has been widely available since the early 2000s.

Is it worth playing?

Probably not for more than thirty seconds. The novelty wears off the moment you realize the song isn't going to change and the gameplay isn't going to get deeper. But as a historical artifact? It’s fascinating. It’s a precursor to the modern "shitposting" culture. Before there were ironic memes and deep-fried images, there was Hong Kong 1997.

Misconceptions and Urban Legends

- The "Dead Man" is Kurosawa: False. It’s a victim of a real-world conflict, likely from a news broadcast or documentary.

- Nintendo Sued Them: Surprisingly, no. Because it was never an "official" licensed game and was sold on floppy disks through the black market, it stayed under the radar until it was too old for anyone to care.

- It’s a Secret Masterpiece: It’s really not. It’s bad. It’s intentionally bad.

Actionable Steps for Retrogaming Curious

If you're going down the rabbit hole of weird SNES history, don't just stop at the Hong Kong 1997 game over screen. There is a whole world of unlicensed "multicarts" and bootlegs that tell the story of gaming's fringe.

- Research "Kusoge": Look into other titles like Death Crimson or Plumbers Don't Wear Ties. They share that same "why does this exist?" DNA.

- Check Out Homebrew History: If you're a developer, look at how people coded for the SNES without official kits. It’s an impressive feat of reverse engineering, even for a game this terrible.

- Support Archival Projects: Sites like The Cutting Room Floor (TCRF) document the hidden files and assets in games like this. It's where the most interesting discoveries are made.

The legacy of Hong Kong 1997 isn't the game itself, but the way it forced us to look at the boundaries of what a video game could be—and what it could get away with. It remains a bizarre, uncomfortable, and oddly permanent stain on the history of the Super Famicom.