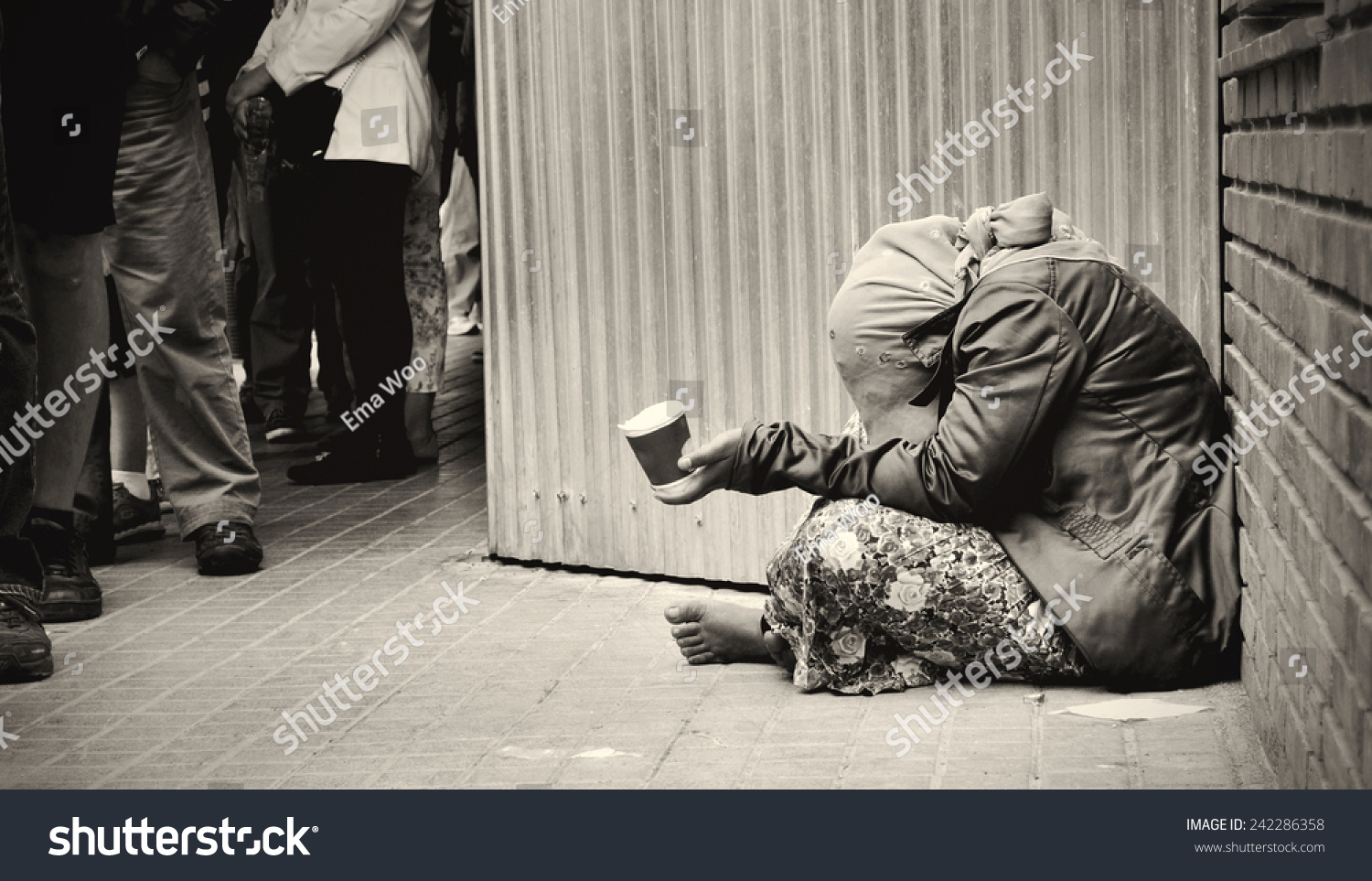

You’re stopped at a red light. Maybe you’re walking to grab a coffee. Someone is standing there with a cardboard sign, and suddenly, that internal tug-of-war starts. Do you look? Do you dig for a five-dollar bill? Do you feel guilty for staring at your phone? We’ve all been there. It’s an uncomfortable, deeply human intersection of poverty and public space. But the reality of homeless begging for money is way more complex than just "lazy people" or "scammers," and it's also different from the "helpless victim" trope we see in movies. It is a survival strategy, plain and simple.

Most of us think we understand the "rules" of the street. We assume people are out there because they want drug money or because they’ve "given up." Honestly, that’s a massive oversimplification that ignores how the actual economy of being unhoused works. It’s a job. A grueling, demoralizing, low-paying, and often dangerous job.

The Brutal Math of the Sidewalk

People often ask how much someone actually makes while panhandling. There is this persistent urban legend about "professional beggars" who drive off in Mercedes-Benzes at the end of the day. While a few high-profile fraud cases occasionally make the local news, they are extreme outliers. Research from organizations like the National Alliance to End Homelessness and various regional studies (like those conducted in San Francisco or Chicago) paints a much bleaker picture.

On average, someone engaged in homeless begging for money might pull in between $10 and $30 on a "normal" day. Some days, they might hit $50 if the weather is perfect or the location is prime. Think about that. That’s below minimum wage in almost every American city. You’re sitting on concrete for eight to ten hours, enduring the elements and the psychological toll of being ignored by thousands of people, all for the price of a fast-food meal and maybe a pack of cigarettes or a bus pass.

It isn't a get-rich-quick scheme. It’s a desperate attempt to bridge the gap between "nothing" and "just enough to survive the next twelve hours."

Why not just go to a shelter or get a job?

This is the question that gets yelled out of car windows. It sounds logical if you’ve never navigated the social services system. First, many shelters are "high-barrier," meaning you can't bring your dog, your partner, or your only belongings. If you have a mental health crisis or a struggle with addiction, you might be barred entry. Plus, shelters are often full by 4:00 PM. If you’re standing on a corner trying to get enough money for a meal, you’ve already missed your chance at a bed.

And the job argument? Try applying for a position at a grocery store without an address, a working phone, a place to shower, or a way to keep your clothes clean. It's nearly impossible. The "street economy" becomes the only economy available.

🔗 Read more: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

The Psychological Weight of the Cardboard Sign

The act of homeless begging for money isn't just about the cash. It’s about visibility—and the lack of it.

Sociologists often talk about "social death." This is what happens when a person is treated as if they don't exist. When you walk past someone begging and refuse to make eye contact, you're participating in a ritual of invisibility. For the person on the sidewalk, this is soul-crushing. Imagine spending your entire day being treated as a literal ghost or an obstacle.

Many folks who panhandle report that the money is secondary to the interaction. A "hello" or a "sorry, I don't have anything today" is often more valuable for their mental health than a silent quarter dropped into a cup. It’s an acknowledgement of their humanity.

But we have to be real about the risks too.

- Violence: People on the streets are significantly more likely to be victims of crime than perpetrators.

- Legal Trouble: Many cities have "anti-panhandling" ordinances. This creates a cycle where someone is fined for begging, can't pay the fine, and ends up with a warrant, making it even harder to get housing later.

- Health: Standing or sitting on cold pavement for hours leads to circulation issues, respiratory infections, and chronic pain.

To Give or Not to Give?

This is the big ethical dilemma. You’ll hear experts on both sides. Some advocates say you should always give cash because the individual knows what they need most in that moment—whether it's socks, a sandwich, or even a beer to stave off withdrawal symptoms (which can be fatal for long-term alcoholics). This is the "harm reduction" philosophy. It respects the person's autonomy.

On the flip side, some service providers suggest that giving cash "enables" a life on the street. They argue that the money is better spent on structural solutions like "Housing First" initiatives.

💡 You might also like: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

The truth? It’s personal.

If you feel comfortable giving, give. If you don't, don't. But don't judge the person for how they spend the five bucks. If you were sleeping on a sidewalk in December, you’d probably want something to take the edge off, too.

The Changing Face of the Street

We’re seeing a shift in how homeless begging for money looks. Since the 2020 pandemic and the subsequent housing crisis, the "typical" person on the corner has changed. You're seeing more seniors. More families. More people who actually have jobs but can't afford the $2,000-a-month rent in their city.

In places like Seattle, Los Angeles, and Austin, the visibility of homelessness has sparked intense political debate. But the debate often focuses on "sweeps" and "cleanup" rather than "why can't this person afford a roof?" Begging is a symptom. It’s the fever, not the infection.

The infection is a lack of affordable housing, a broken mental healthcare system, and an economy that leaves the most vulnerable behind.

Practical Ways to Actually Help

If you want to move beyond the red-light guilt and do something that actually moves the needle, there are better ways than just handing out spare change (though, again, that’s fine to do if you want).

📖 Related: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

1. Support Housing First Programs

Data consistently shows that the most effective way to stop panhandling is to give people homes. Not "shelters," but actual apartments with supportive services. Programs like those in Utah (which famously reduced chronic homelessness by 90% at one point) show that when people have a door they can lock, they stop needing to beg.

2. Carry "Care Kits"

Instead of cash, keep a few bags in your car with:

- High-protein snacks (jerky, nuts)

- Socks (the most requested item at shelters)

- Unscented baby wipes

- Gift cards to local fast-food places (this gives them a place to sit inside and use a bathroom)

3. Advocate for Policy Change

Stop supporting "anti-vagrancy" laws that just move people from one block to the next. Support zoning changes that allow for tiny homes, ADUs, and low-income housing in your neighborhood.

4. Just Be a Human

If you don't have money, just say, "I'm sorry, I don't have anything today, but I hope you have a safe afternoon." That five-second interaction can be the only time that person is treated like a person all day.

The reality of homeless begging for money is that nobody wants to be doing it. It’s a last-resort survival tactic in a world that has become increasingly expensive and indifferent. Whether you choose to open your wallet or not, understanding the systemic failures that lead someone to that corner is the first step toward a solution that actually works for everyone.

Actionable Next Steps

- Research your local "Point in Time" (PIT) count. This will give you the real stats on homelessness in your specific city, rather than relying on national averages or assumptions.

- Locate your nearest "Day Center." Unlike overnight shelters, day centers are where people go to get mail, use the internet for job searches, and do laundry. They are often underfunded and desperately need supplies like laundry detergent or transit passes.

- Program your phone. Save the number for your city's non-emergency outreach team (like 311 in many US cities). If you see someone who looks like they are in medical or mental distress, calling outreach is often much safer and more effective for the individual than calling the police.

- Check your bias. Next time you feel annoyed by a panhandler, ask yourself: "Am I mad at the person, or am I mad that I'm being forced to see a problem I don't know how to fix?" Recognition of that discomfort is where real advocacy starts.