You’ve probably seen one without thinking twice about it. Maybe it was at a construction site, or perhaps you were watching a mechanic yank an entire engine block out of a truck like it was nothing but a bag of groceries. That’s the hoist and pulley system at work. Honestly, it’s one of those bits of ancient technology that we haven’t really "beaten" yet. Sure, we’ve added sensors and electric motors, but the core math? That hasn't changed since Archimedes was running around Greece.

It's basically a cheat code for the universe.

Physics is usually a pain. Gravity is constantly trying to keep things on the ground, and your back is usually the first thing to complain when you try to fight it. But when you introduce a pulley, you aren't just moving a rope. You’re redirecting force. You’re trading distance for ease. It’s a trade-off that makes modern infrastructure possible. Without these systems, every warehouse in the world would grind to a halt, and your local elevator would just be a very small, very dark room where you sit and wait for nothing to happen.

The Brutal Reality of Mechanical Advantage

Most people think a pulley just lets you pull down to move something up. That’s a fixed pulley. It's helpful, sure, because pulling down lets you use your body weight, but it doesn't actually make the load lighter. To get the "magic" happening, you need a moveable pulley.

When you attach the pulley to the load itself, you’re suddenly sharing the weight between two lengths of rope. This is the "Mechanical Advantage." If you have a 100-pound crate and you set up a basic two-rope system, you only feel 50 pounds of tension. The catch? You have to pull twice as much rope. Physics is a fair dealer; it never gives you something for nothing.

Why Your Gym Equipment Feels Different

Ever notice how 50 pounds on a cable machine at the gym feels way lighter than a 50-pound dumbbell? That’s the hoist and pulley system messing with your ego. Gym designers use "compound pulleys" (often called a block and tackle) to make the motion smooth and manageable. If they didn't, the jerky movements of raw weight would probably snap a few tendons.

In a "Block and Tackle" setup, you’ve got multiple pulleys encased in frames (blocks). The more loops of rope (falls) you have going between the blocks, the more the weight is distributed.

It’s a bit of a rabbit hole. You add more pulleys, the weight feels like feathers, but suddenly you’re pulling 40 feet of rope just to lift a box five feet off the ground. There’s a point of diminishing returns where the friction of the pulleys themselves starts to eat up all your gains. Real-world engineers have to balance this. They can't just keep adding wheels forever.

The Difference Between a Hoist and a Winch

People mix these up constantly. It’s a pet peeve for riggers.

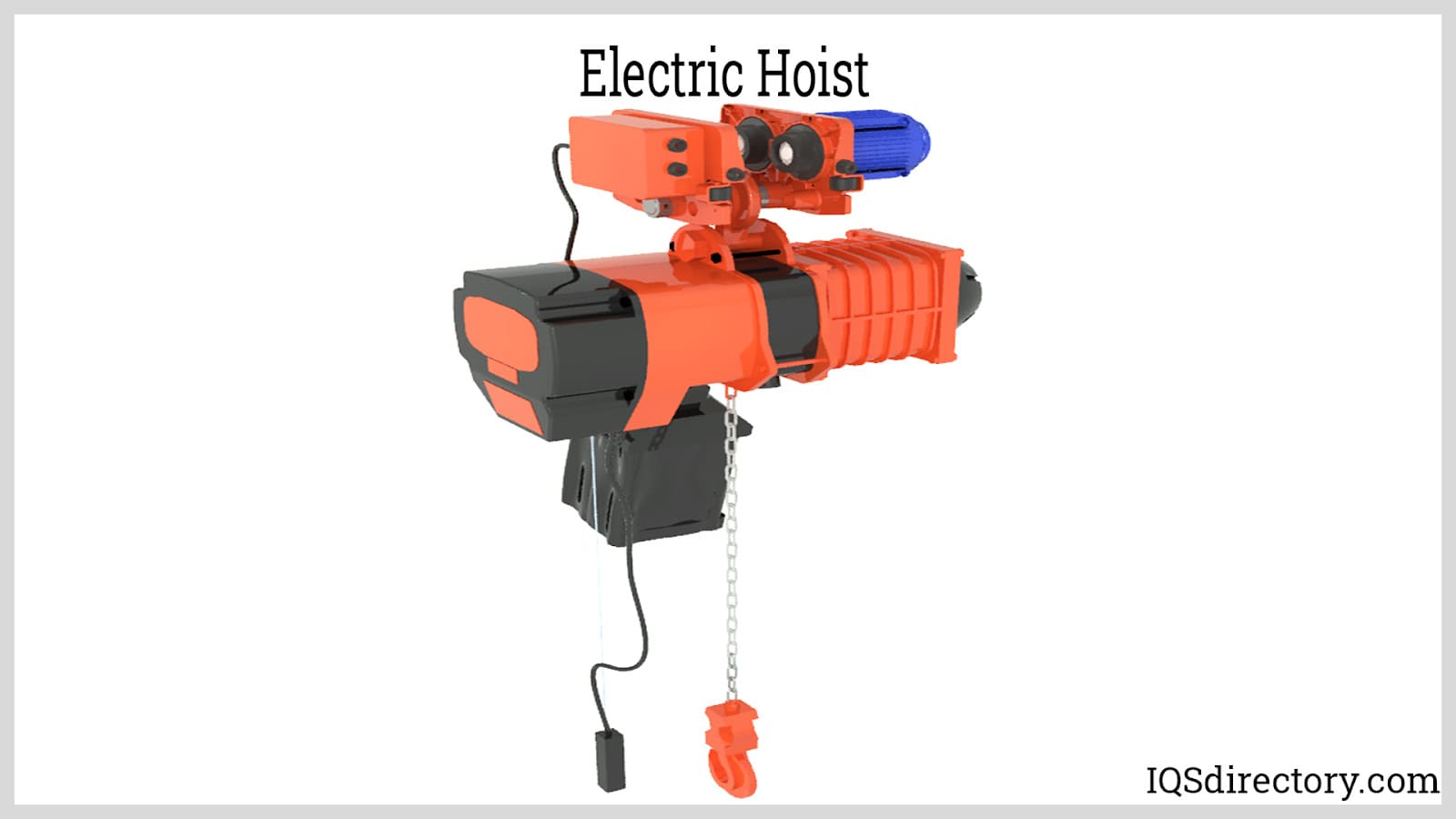

Basically, a hoist is designed for vertical lifting. It has a specific braking system that is "fail-to-safe." This means if the power goes out or the handle slips, the load stays put. It won't come crashing down on your head.

A winch, on the other hand, is usually for horizontal pulling—like pulling a Jeep out of a mud hole. Winches often use "dynamic braking," which isn't always rated to hold a dangling weight indefinitely. If you try to use a standard recovery winch as a vertical hoist, you’re asking for a catastrophic failure. Don't do it.

Chain Hoists: The Unsung Heroes of the Garage

If you go into any serious auto shop, you'll see a manual chain hoist. They look like heavy, greasy metal gourds hanging from the ceiling. These use a "differential pulley" logic.

Inside that metal casing, there are two pulleys of slightly different sizes joined together. As you pull the hand chain, one pulley lets rope (or chain) out while the other pulls it in. Because their diameters are just a tiny bit different, the load moves incredibly slowly, but with massive force. You can lift a 2,000-pound V8 engine with one hand while sipping a coffee with the other.

Material Science is the Real Bottle Neck

We can design a pulley system to lift the Titanic, but we’re limited by the "tensile strength" of the materials. Back in the day, we used hemp rope. Hemp is great until it rots or gets wet and stretches.

✨ Don't miss: Getting Your Walmart 65 Inch TV Mount Right Without Dropping Three Large on the Floor

Then came wire rope. This isn't just "wire." It’s a complex braid of steel strands designed to flex without snapping. According to the OSHA guidelines for rigging, even a single kink in a steel wire rope can reduce its lifting capacity by 50% or more. That’s why professional riggers spend so much time inspecting their gear. They’re looking for "bird-caging"—where the strands unravel—or tiny broken wires called "fishhooks."

Synthetic Slings: The Modern Twist

Lately, there’s been a shift toward high-performance synthetics like Dyneema. It’s lighter than steel and, pound for pound, stronger. But it has a weakness: heat. If a synthetic rope rubs against a pulley too fast, the friction can literally melt the fibers. In a hoist and pulley system, heat is the enemy.

How to Not Break Your Stuff (or Your Bones)

If you're planning on rigging something at home—maybe a deer hoist or a way to get your kayak into the garage rafters—you need to understand the "Angle of Pull."

This is where most DIYers fail. If you have two ropes holding a weight, and they are perfectly vertical, each rope takes 50% of the load. But as you spread those ropes apart to form a "V" shape, the tension on those ropes increases exponentially.

- At a 45-degree angle, the stress on your anchors is significantly higher than the weight of the object.

- At a 120-degree angle, each rope is actually pulling with a force equal to the entire weight of the object.

- If you try to get a rope perfectly horizontal (180 degrees) while holding a weight in the middle, the tension becomes theoretically infinite. Something will snap.

The Future: Magnetic Levitation and Beyond?

Are we still going to be using ropes and wheels in 100 years? Probably.

While we have things like linear motors and maglev tech, they are expensive and require constant power. A hoist and pulley system is "passive." Once the brake is set, gravity does the work of holding it. It’s reliable. It’s elegant.

We are seeing "smart hoists" now, though. Brands like Konecranes and Columbus McKinnon are integrating load cells into the pulleys. These systems can "feel" if a load is off-center or if it’s snagged on something, and they’ll shut down the motor before the cable snaps. It’s basically taking the "expert feel" of an old-school crane operator and putting it into a microchip.

Real-World Case: The High-Rise Dilemma

The biggest challenge right now isn't lifting weight; it's the weight of the rope itself. In ultra-tall skyscrapers (like the Burj Khalifa), the steel cables for elevators become so long that they actually weigh more than the elevator car. This is a massive engineering hurdle.

👉 See also: K2-18b and the Search for Life 120 Light Years From Earth: What’s Actually True?

The solution? Carbon fiber "UltraRope." Companies like KONE are using these to replace traditional steel. It’s incredibly light, meaning the hoist and pulley system doesn't have to waste energy just lifting its own hardware.

Common Misconceptions That Get People Hurt

- "Any pulley can handle any rope."

Wrong. The "sheave" (the wheel inside the pulley) has a groove specifically sized for a certain diameter of rope. If the rope is too big, it chafes. If it's too small, it gets wedged in the gap and gets crushed. - "Knots don't matter."

A common bowline or figure-eight knot can reduce the strength of your rope by 20% to 40%. Professional systems use "swaged" ends or "thimbles" to avoid sharp bends that weaken the material. - "Pulleys are 100% efficient."

Nope. Every time a rope bends over a wheel, you lose energy to friction. In a cheap plastic pulley, you might lose 10% of your effort just turning the wheel. High-end bearings are a must for heavy lifts.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Lift

If you’re actually going to use a hoist and pulley system, don't just wing it.

First, calculate your load. Don't guess. If you're lifting an engine, look up the dry weight. Then, add a 25% "safety buffer" for the weight of the fluids and the hardware itself.

Second, check your anchor point. A hoist is only as strong as the beam it’s hanging from. If you’re bolting a hoist into a wooden rafter, you aren't just checking the bolt; you're checking the integrity of the wood. Use "backing plates" to spread the load so the bolts don't just pull through the grain.

Third, establish a "No-Go Zone." Never, ever stand under the load. It doesn't matter if the equipment is brand new. Cables can "whip" when they snap, traveling at speeds that can literally cut a person in half.

Finally, lubricate the sheaves. A squeaking pulley isn't just annoying; it’s a sign of metal-on-metal friction that is eating away at your mechanical advantage and creating heat that could degrade your rope. A little bit of lithium grease goes a long way.

Physics isn't going to give you a pass just because you're in a hurry. Treat the system with a bit of respect, and it'll let you move mountains. Ignore the rules, and gravity will win every single time.

Keep your cables clean, keep your bearings greased, and always watch your angles. That's how you make a hoist and pulley system work for you instead of against you.