Walk onto the flight deck of the HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier and you’ll realize pretty quickly that photos don't do it justice. It’s huge. Honestly, "huge" feels like an understatement when you're standing on four acres of sovereign British territory that can move at 25 knots. We are talking about 65,000 tonnes of steel, a specialized design that looks nothing like the American Nimitz-class giants, and a price tag that makes taxpayers wince.

But here’s the thing.

Size isn’t everything in modern naval warfare, and the HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier has spent as much time in the headlines for its "teething issues" as it has for its power projection. People love to complain about the leaks or the fact that we had the ship before we had enough F-35B jets to fill it. It’s a bit of a lightning rod for criticism. Yet, if you look at the actual tech—the twin islands, the highly automated weapon handling, and the way it integrates with NATO—you start to see a very different picture. This isn't just a boat. It's the centerpiece of a global maritime strategy that the UK is still trying to figure out.

The Twin Island Design: Weird or Genius?

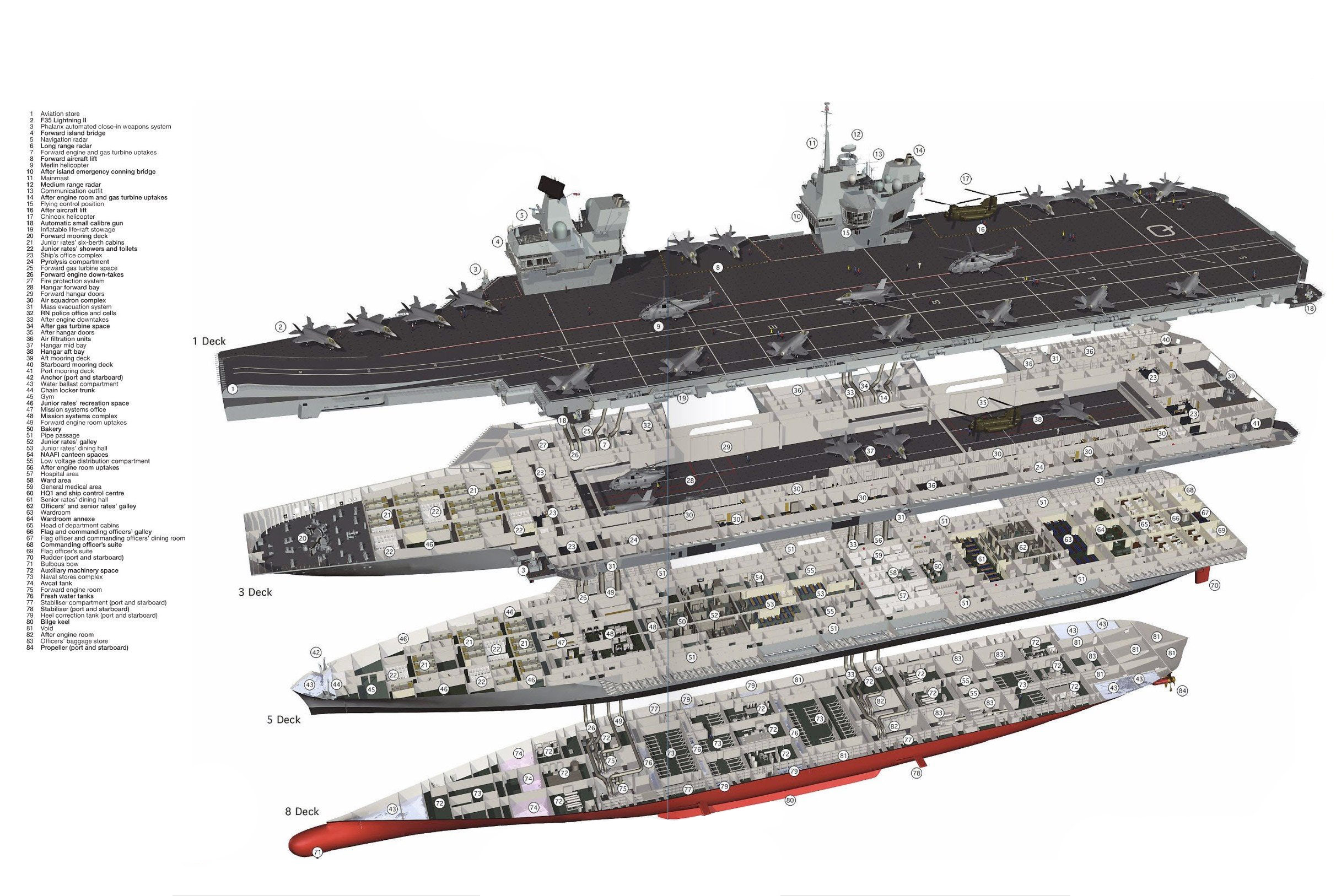

The first thing everyone notices is the two towers. Most carriers have one big "island" on the starboard side. The HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier went a different route. Why? Basically, it’s about aerodynamics and efficiency. One island is for navigating the ship (the Bridge), and the other is for "Flyco" (Flight Carrier Control). This separation isn't just for show. It reduces wind turbulence over the deck, which is a big deal when you’re trying to land a vertical-takeoff jet in a North Atlantic gale. Plus, it offers redundancy. If one island takes a hit in combat, the other can theoretically pick up the slack.

Engineers at BAE Systems and Thales didn’t just wake up and decide to be different. The placement of these islands is tied directly to the gas turbine exhausts. Unlike US carriers that use nuclear power, the Queen Elizabeth runs on Integrated Full Electric Propulsion (IFEP). This uses Rolls-Royce MT30 gas turbines. Because they aren't nuclear, they need massive "funnels" to get rid of exhaust. Splitting the islands allowed the designers to optimize the internal layout for the engine rooms below.

The F-35B Lightning II Problem

You can’t talk about the HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier without talking about the planes. Or the lack of them. For a few years, the "carrier without planes" joke was the favorite weapon of every defense critic in London. The UK opted for the F-35B—the Short Take-Off and Vertical Landing (STOVL) variant.

👉 See also: How to Log Off Gmail: The Simple Fixes for Your Privacy Panic

It was a choice.

By using a "ski jump" ramp instead of the catapults (CATOBAR) used by the US Navy, the Royal Navy saved billions in development and manning costs. Catapults are notoriously difficult to maintain and require a massive amount of fresh water or complex electrical systems. But the trade-off is real. The F-35B can’t carry as much fuel or ordnance as the F-35C that launches off American decks. It also can’t carry heavy "buddy-tanker" refueling pods or large Airborne Early Warning (AEW) aircraft like the E-2D Hawkeye. Instead, the UK relies on the Crowsnest radar system fitted to Merlin helicopters. It works, but it doesn't have the same range or "eyes in the sky" persistence as a fixed-wing plane.

Automation and the "Lean" Crew

Here is a wild stat: a US carrier of a similar size usually needs about 3,000 to 5,000 sailors. The HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier can run with a core crew of about 700 to 1,600 (including the air wing). That’s a massive difference.

How do they do it? Automation.

The Highly Automated Weapon Handling System (HAWHS) is the secret sauce. Imagine a giant, computerized warehouse inside the ship. Pallets of munitions are moved from the magazines to the flight deck by remote-controlled "mules" and specialized lifts. In the old days, hundreds of sailors would be hand-rolling bombs and dragging carts. Now, a handful of people behind screens move the firepower. It’s efficient, but it also creates a vulnerability. If the software glitches or the power fails, you can't exactly "man-handle" a two-ton missile up six decks easily.

✨ Don't miss: Calculating Age From DOB: Why Your Math Is Probably Wrong

The 2021 Global Deployment: A Real Test

In 2021, Carrier Strike Group 21 (CSG21) took the HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier on a 28,000-mile journey to the Indo-Pacific. It wasn't just a British parade. It included a US Navy destroyer, a Dutch frigate, and a squadron of US Marine Corps F-35Bs. This "plug and play" interoperability is exactly what the Ministry of Defence (MoD) is betting on.

The mission sent a message to China and Russia: the UK is back in the carrier game. But it also highlighted the logistical strain. Keeping a carrier group supplied that far from home requires a massive "tail" of support ships. The Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) is currently struggling with aging ships and recruitment. Without those tankers and stores ships, the carrier is basically a very expensive sitting duck. You've got to have the groceries to keep the kitchen running.

Reliability Scandals and the "Propeller" Incident

We have to address the elephant in the room: the mechanical failures. In early 2024, the HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier had to pull out of a major NATO exercise, Steadfast Defender, at the last minute because of an issue with a propeller shaft coupling. It was embarrassing. Its sister ship, HMS Prince of Wales, had already suffered a similar, much more serious breakdown off the Isle of Wight a couple of years prior.

Critics jumped all over it. "The Great British Leaking Carrier" became a common headline. To be fair, these are "first-of-class" vessels. They are prototypes that happen to be 900 feet long. The US Ford-class carriers had even worse problems with their electromagnetic catapults and elevators. Naval engineering is hard. But when you only have two carriers, having one in dry dock for months on end feels like a crisis.

Is it Actually Defensible?

In an era of hypersonic missiles and "carrier-killer" drones, people ask if the HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier is obsolete before it even hits its prime. It’s a fair question. A Chinese DF-21D missile could theoretically sink it from hundreds of miles away.

🔗 Read more: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

However, naval experts like those at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) argue that a carrier is never alone. It’s the center of a "bubble." Type 45 destroyers like HMS Dragon or HMS Diamond provide the air defense, using the Sea Viper missile system to swat away threats. Astute-class submarines lurk underneath to handle underwater threats. The carrier is a mobile airfield that can move 500 miles in a day. It’s a lot harder to hit than a static airbase in Cyprus or Qatar.

Making Sense of the Cost

The program cost around £6.2 billion for both ships. That sounds like a lot—because it is—but compared to a single US Ford-class carrier ($13 billion+), the UK got a bargain. The real cost isn't the hull; it's the 50-year life cycle. Maintaining the F-35 jets, paying the specialized crew, and upgrading the sensors will cost tens of billions more.

Some argue that money should have been spent on 20 more frigates or a massive drone fleet. But frigates can't provide air cover for a task force. Drones can't (yet) perform the complex multi-role missions of a manned stealth fighter. The HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier gives the UK a seat at the "top table" of military powers that no other platform can.

What's Next for the Big Q?

The future of the HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier is all about "Project Vixen" and "Project Ark Royal." These are the Royal Navy's initiatives to bring fixed-wing drones to the deck. We aren't talking about small surveillance drones; we're talking about jet-powered loyal wingmen that can jam enemy radar or carry extra missiles.

By 2030, the flight deck will likely look very different. You’ll see a mix of F-35Bs and autonomous combat aircraft. This might even lead to the retrofitting of "arrestor wires" or small catapults specifically for drones. The ship was built with enough modular space to be upgraded over several decades.

Actionable Insights for Following the Carrier's Progress

If you're interested in whether this massive investment is actually paying off, don't just look at the headlines. Pay attention to the "deployment cycles." A carrier is only useful if it’s at sea.

- Watch the RFA: Keep an eye on the Royal Fleet Auxiliary's new "Solid Support Ship" program. The HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier is only as good as the ships that feed it. If those don't get built, the carrier stays in Portsmouth.

- Jet Numbers: The current goal is to eventually have enough F-35Bs to maintain a "credible" strike force. Until the UK reaches about 60 to 74 airframes, the carrier will continue to rely on US Marine Corps help for full-strength deployments.

- The Drone Integration: Follow the trials of "Mojave" or similar STOL (Short Take-Off and Landing) drones on the deck. This is the clearest indicator of how the ship will adapt to 21st-century warfare.

The HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier is a massive bet on the future of British influence. It's a complicated, expensive, and sometimes frustrating piece of machinery. But in a world where maritime trade routes are increasingly under threat, having a four-acre piece of "home" that can park itself anywhere in the ocean is a capability you only appreciate once you don't have it.