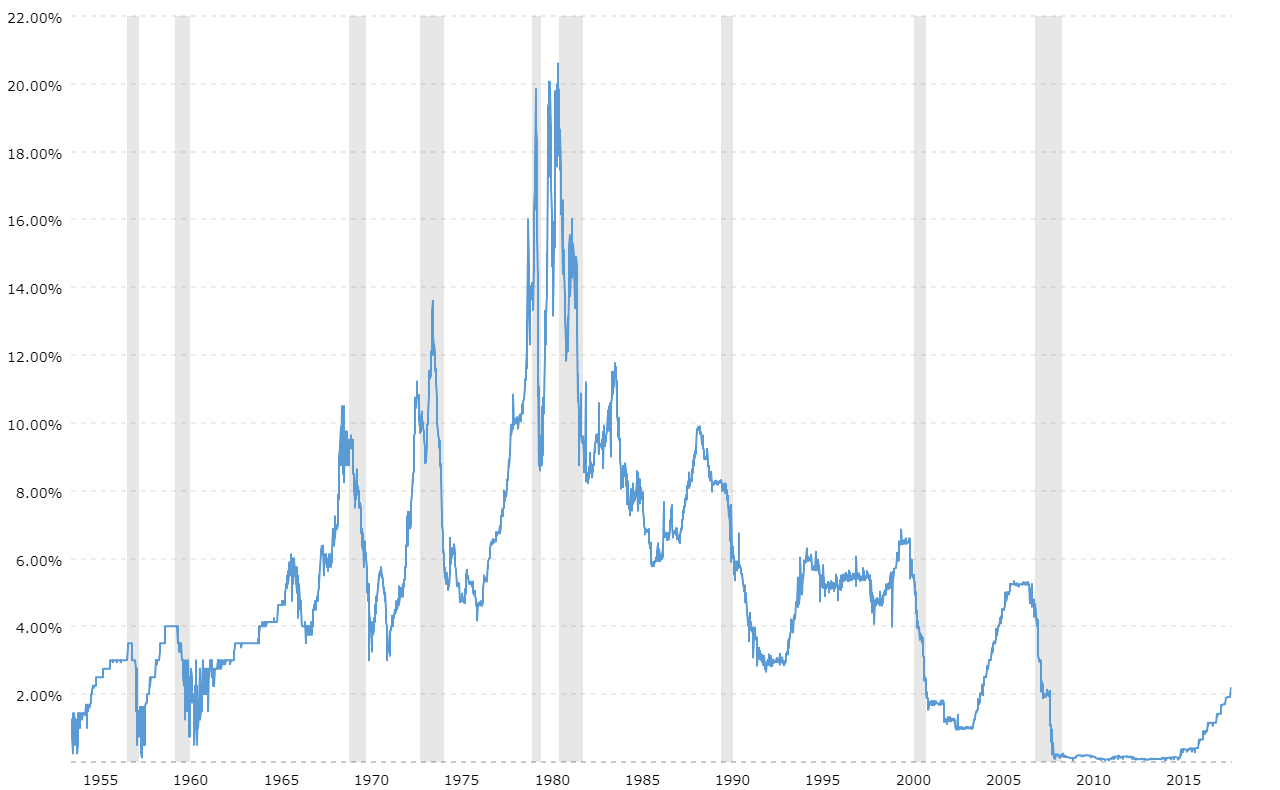

Money isn't free. Most of us feel that in our bones when we look at a mortgage statement or a credit card bill, but the actual "price" of money—the federal funds rate—is a moving target that has swung wildly over the last fifty years. If you look at the history of Fed funds rate changes, you aren't just looking at a chart of boring central bank meetings. You’re looking at the pulse of every major American crisis, from the gas lines of the seventies to the housing bubble and the post-pandemic inflation spike.

It's basically the steering wheel of the economy. When the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets, they aren't just guessing. They're trying to hit a "neutral" rate that keeps people employed without making a loaf of bread cost twenty bucks. They fail. A lot. Honestly, the history of these rate shifts is mostly a story of the Fed being surprised by reality and then scrambling to catch up.

The Volcker Shock and the 20% Nightmare

People talk about 5% or 7% interest rates today like they're the end of the world. They aren't. Not even close. If you want to see what a real aggressive move looks like, you have to look back to 1979. Paul Volcker took the reins of the Federal Reserve when inflation was a literal monster eating the American middle class. We're talking 13% or 14% year-over-year price increases.

Volcker didn't just nudge things. He nuked them.

By 1981, the Fed funds rate hit an all-time peak of 20%. Imagine that for a second. Your local bank was probably charging 21% or 22% for a basic loan. It worked, sort of. It crushed inflation, but it also caused a brutal recession and made Volcker one of the most hated men in Washington for a few years. Farmers were literally driving tractors to the Fed building to protest. This era set the stage for how we view the history of Fed funds rate changes today: the idea that the Fed must be willing to "cause pain" to save the dollar.

👉 See also: 5-year mortgage rate forecast: Why waiting for 3% is a mistake

The Great Moderation and the 1990s Pivot

After the chaos of the eighties, the Fed entered what economists like to call the "Great Moderation." This was the Alan Greenspan era. Greenspan was basically treated like a wizard. He started using the Fed funds rate with more surgical precision. In 1994, for instance, he doubled the rate from 3% to 6% in just twelve months.

Why? Because he saw a "ghost" of inflation that hadn't even shown up in the data yet.

It was a pre-emptive strike. It worked. The economy didn't crash, and the 90s became one of the longest periods of expansion in U.S. history. This gave everyone a false sense of security. It made people believe that the Fed could perfectly "fine-tune" the economy forever. We now know that was a bit of a delusion, but at the time, the Fed felt invincible.

When the Rate Hit Zero: The 2008 Breaking Point

Everything changed in 2008. When the subprime mortgage market imploded and Lehman Brothers went under, the Fed realized that their usual toolkit was broken. Ben Bernanke, who was a scholar of the Great Depression, knew he couldn't just lower rates by a quarter-point and hope for the best.

The Fed slashed rates to the "zero bound"—effectively 0% to 0.25%—for the first time ever.

They stayed there for seven years. Seven. Years.

This was a massive departure in the history of Fed funds rate changes. Before 2008, rates were usually somewhere between 3% and 5%. By keeping them at zero, the Fed was trying to force people to spend and invest because keeping money in a savings account paid literally nothing. This created a "cheap money" era that fueled the tech boom, the rise of companies like Uber and Airbnb that didn't need to make a profit for a decade, and, eventually, the massive asset bubbles we see today.

The Transitory Mistake of 2021

Fast forward to the post-COVID world. This is where the Fed really stepped in it. In 2020, they slammed rates back to zero to prevent a total economic collapse during the lockdowns. It worked. Maybe too well. By 2021, prices were starting to climb. Used cars were expensive. Rent was soaring.

Jerome Powell and the Fed kept saying inflation was "transitory." They didn't move the rate. They waited. And waited.

Then 2022 hit, and they realized they were miles behind the curve. What followed was the fastest tightening cycle in forty years. They hiked rates at seven consecutive meetings in 2022, including four massive 75-basis-point jumps. This wasn't surgical. This was a panic move. They had to break the back of inflation, and they didn't care if the stock market took a haircut to get it done.

The Real Correlation: Rates vs. Unemployment

It's a simple see-saw.

- High rates = High borrowing costs = Slow business growth = Higher unemployment.

- Low rates = Cheap borrowing = Expansion = Lower unemployment.

But there is a lag. A big one. Usually, it takes 12 to 18 months for a Fed rate change to actually ripple through the economy. That’s why the Fed is always "flying blind." By the time they see the effect of a rate hike, they might have already hiked too much.

What History Actually Teaches Us

If you study the history of Fed funds rate changes, you’ll notice a pattern: the Fed almost always keeps rates too low for too long, then keeps them too high for too long. They are rarely "just right."

Take the 2000 dot-com bubble. The Fed hiked to 6.5% to cool things off, but by the time the hikes landed, the bubble was already popping. Then they cut all the way to 1% by 2003, which many people—including legendary economist John Taylor—argue helped create the housing bubble that wrecked the world in 2008. It’s a cycle of over-correction.

Actionable Insights for the Current Market

So, what do you actually do with this information? Understanding the history helps you ignore the daily noise and focus on the macro trends.

Watch the Yield Curve

Historically, when short-term rates (like the Fed funds rate) stay higher than long-term rates (like the 10-year Treasury), it’s called an inversion. In the history of Fed moves, an inverted yield curve has predicted almost every recession since the 1950s. If the Fed is keeping rates high while the market is "pricing in" lower rates in the future, get defensive.

Ignore the "Pivot" Hype

Wall Street is obsessed with the "pivot"—the moment the Fed starts cutting. But history shows that the first few cuts often happen because something is breaking. You don't necessarily want to buy the first cut; you want to wait to see if the Fed is cutting because inflation is down or because the labor market is bleeding out.

Fixed vs. Floating Debt

The biggest takeaway from the Volcker and Powell eras is that "low for longer" is never a guarantee. If you’re a business owner or a homeowner, the periods of low rates in the history of Fed funds rate changes are the exception, not the rule. Locking in fixed rates during "panic" low periods is the single best wealth-preservation move you can make.

The Fed is currently trying to find that "soft landing"—lowering inflation without causing a recession. History says they probably won't stick the landing perfectly. They almost never do. But by knowing where we've been, you can at least see the cliff before the car goes over it.

📖 Related: Naira to US Dollar: What Most People Get Wrong About the Exchange Rate

Your Next Strategic Moves

Audit your debt exposure immediately. Check any variable-rate loans or HELOCs. Even if the Fed is expected to cut rates, the "higher for longer" philosophy usually keeps bank lending rates elevated for months after the Fed moves. Diversify into short-term liquid assets like T-bills when rates are peaking, as these offer a "risk-free" return that hasn't been seen for much of the last twenty years. Finally, track the PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures) index, not just the CPI. The Fed prefers the PCE for their decision-making, so if you want to know what they'll do next, look at the data they actually care about.