Ever looked at a poll and wondered how anyone could actually believe it? You're not alone. Honestly, we’ve been obsessed with tracking how much we like—or hate—the person in the Oval Office since George Gallup started asking the question in the 1930s. But looking back at historical presidential approval ratings, you start to see that the numbers rarely tell the whole story. They’re more like a fever dream of American anxiety and occasional, fleeting unity.

Basically, these numbers are a roller coaster.

The Highs and Lows of Public Love

If you want to talk about records, you have to talk about George W. Bush. After the 9/11 attacks in 2001, he hit an astronomical 90% approval rating. It’s the highest Gallup has ever recorded. It wasn't necessarily about policy; it was a "rally 'round the flag" moment where the country basically decided to hold its breath together.

But gravity is a thing. By the time 2008 rolled around and the economy was cratering, he was scraping the bottom at 25%.

Harry Truman is another weird one. People sort of love him now—historians usually rank him in the top ten—but his contemporaries? Not so much. In February 1952, Truman bottomed out at 22%. That’s the lowest ever. Between a messy war in Korea and corruption scandals, people were just done. It’s a classic case of how historical presidential approval ratings can be totally different from historical reputation.

The JFK Exception

John F. Kennedy is basically the gold standard for popularity while in office. He averaged a 70.1% approval rating over his entire presidency. That is nuts. Most presidents would give their left arm for a single week at 70% today.

- He never really had a "bad" year.

- Even after the Bay of Pigs disaster, his numbers actually went up because he took responsibility.

- His retrospective approval today? It’s around 90%.

Why Historical Presidential Approval Ratings Are Changing

You've probably noticed that things feel different lately. They are. We’ve entered the age of the "polarized floor."

In the past, a president's approval would swing wildly based on whether the economy was good or if we were winning a war. Now? Your party matters more than your performance. Since around the George W. Bush years, the gap between how Republicans and Democrats view the same person has become a canyon.

Donald Trump, for instance, had a remarkably stable—but low—approval rating. He never broke 50% in Gallup's tracking, but he also never completely bottomed out because his base was so solid. His average was 41%, and it didn't move much despite everything. Joe Biden followed a similar path, starting higher but eventually settling into that same low-40s trench as inflation and age concerns bit into his support.

The "Misery Index" and Your Wallet

It’s mostly about the money. Kinda obvious, right?

Political scientists often look at the "Misery Index"—a simple combo of the unemployment rate and the inflation rate. When that number goes up, approval goes down. Period. Ronald Reagan almost lost his footing early on when unemployment hit 10.8% in 1982. He dropped to 35%. But once the economy "recovered" (depending on who you ask), he surged back up to 68%.

🔗 Read more: Tornado How Does It Form: The Chaos Behind Nature’s Most Violent Spin

Modern Trends to Watch

- The Honeymoon is Dead: Presidents used to get a few months of "let's see what they can do." That's gone. Now, disapproval starts on Day 1.

- The Out-Party Floor: It is now almost impossible for a president to get more than 10% approval from the opposing party.

- Social Media Echoes: Real-time feedback loops mean a bad headline can tank a rating in 48 hours, though they tend to bounce back faster too.

What Most People Get Wrong

People think a low approval rating means a president is "failing" or "bad." But looking at historical presidential approval ratings, we see that some of our most consequential leaders were loathed in their time.

Lyndon B. Johnson passed the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. His reward? His approval plummeted from nearly 80% to the 30s as the Vietnam War escalated and the country fractured over social change. He chose not to run for re-election in 1968 because he knew he was toast. Yet, you can't talk about modern America without him.

Sometimes the right move is the unpopular one. Gerald Ford pardoned Richard Nixon and his approval rating instantly dropped 20 points. It probably cost him the 1976 election. But decades later, the John F. Kennedy Library gave him a "Profile in Courage" award for it.

How to Read the Numbers Today

When you see a new poll drop, don't just look at the top-line number. Look at the "intensity" (strong vs. somewhat approve). Look at the independents—they are the only ones whose numbers actually move anymore.

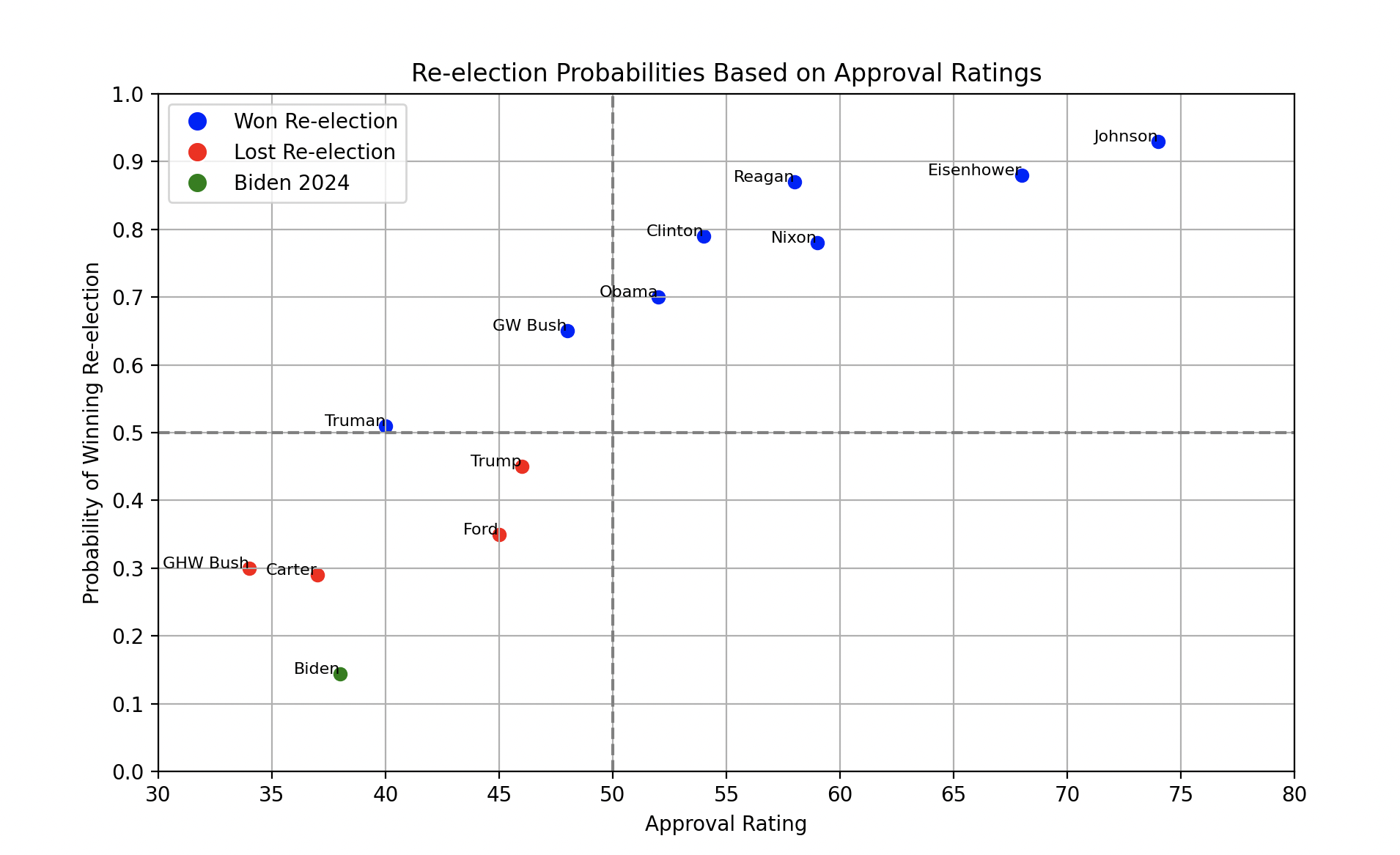

If you're trying to predict an election based on historical presidential approval ratings, the magic number is usually 50%. If an incumbent is at or above 50% on Election Day, they almost always win. If they’re in the low 40s? They’re in serious trouble.

📖 Related: Who is the Leader of Antifa? What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

To really understand how these numbers work, you should check out the Gallup Presidential Job Approval Center. It lets you overlay different presidents' terms to see exactly where they diverged.

Also, keep an eye on the "Consumer Sentiment Index" from the University of Michigan. It usually predicts where approval ratings are headed about three months before the polls catch up. If people feel grumpy at the grocery store today, the president's approval rating will reflect that grumpiness by next quarter.

The most important thing to remember is that these ratings are a snapshot of a mood, not a verdict on a legacy. Truman's 22% didn't stop him from being a "near-great" president in the eyes of history. It just meant that in 1952, everyone was really tired of him.

Next Steps for Deeper Insight:

- Compare the "Misery Index" peaks of 1980 and 2022 against the approval drops of Carter and Biden to see the correlation.

- Research "Rally 'Round the Flag" events to see how long a popularity spike actually lasts (usually about 6 to 9 months).

- Contrast retrospective approval (how we feel now) with job approval (how they felt then) for Richard Nixon to see the impact of time on public perception.