History isn't just a bunch of dates written in dusty textbooks by people who weren't actually there. It's messy. It’s grainy. Sometimes, it’s a bit out of focus. When you look at historical images of world events, you aren't just seeing a frozen second in time; you're seeing a perspective that was curated, often by someone with a heavy tripod and a very specific agenda. Honestly, we tend to treat old photos like objective proof, but they’re often just as biased as a modern-day social media feed.

Think about the first photograph ever taken. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce sat by his window in Burgundy around 1826 and waited eight hours—eight hours!—for the light to burn an image onto a pewter plate. The result, View from the Window at Le Gras, looks like a blurry smudge to the untrained eye. Yet, it changed everything. It started a visual record of our planet that has misled us just as much as it has informed us. We see the past in black and white and assume the world was grayer then. It wasn't. It was vibrant.

The Problem With "Iconic" Historical Images of World History

We've all seen the heavy hitters. The "Migrant Mother" from the Great Depression or the sailor kissing the nurse in Times Square. These are the historical images of world fame that define eras. But there’s a catch. Dorothea Lange, the photographer behind "Migrant Mother," actually asked Florence Owens Thompson to pose in specific ways to evoke more sympathy for the Farm Security Administration’s cause. Thompson later expressed some resentment about it. She felt like a prop.

That’s the thing about "truth" in photography. It’s selective.

When we look at 19th-century photos of the American West or colonial expeditions in Africa, we’re seeing a "civilizing" narrative. Photographers like Edward Curtis spent years documenting Native American tribes, but he sometimes paid his subjects to remove "modern" items like clocks or suspenders to make the photos look more "authentic" and "primitive." He was literally airbrushing the present out of the past to fit a story people wanted to buy. It’s kinda wild when you think about how much of our visual history is essentially a staged production.

✨ Don't miss: Why Palacio da Anunciada is Lisbon's Most Underrated Luxury Escape

Technology Changed the Way We Remember

Early cameras were massive. You didn't just "snap" a photo. You lugged a chemical lab on your back. This meant that for decades, historical images of world conflicts or daily life were static. Dead bodies on a battlefield stayed still; charging cavalry did not. This is why Civil War photography, like the work of Mathew Brady or Alexander Gardner, feels so hauntingly quiet. They couldn't capture the noise of the fight, only the silence of the aftermath.

The Shift to the Leica

Everything flipped in the 1920s. The 35mm Leica camera hit the scene. Suddenly, photographers were mobile. They were invisible. This gave us "The Decisive Moment," a term coined by Henri Cartier-Bresson. This wasn't about staging a portrait; it was about the raw, jagged reality of a man jumping over a puddle or a revolution starting on a street corner.

- The move from glass plates to film rolls meant more photos.

- Faster shutter speeds allowed for the capture of motion, changing our "memory" of speed.

- Darkroom manipulation became the first version of Photoshop.

If you look at Soviet-era historical images of world leaders, you’ll notice people literally disappearing from photos. If you fell out of favor with Stalin, you were brushed out of the frame. It was the ultimate "cancel culture" before the term existed. Nikolay Yezhov, a secret police official, was famously scrubbed from a photo of him standing next to Stalin by the Moscow Canal. One day he’s there, the next, it’s just water.

Why Colorization is Controversial

Lately, there’s been a massive trend in colorizing historical images of world archives. You’ve probably seen them on Reddit or YouTube—vibrant, high-definition versions of WWI trenches or 1920s New York.

🔗 Read more: Super 8 Fort Myers Florida: What to Honestly Expect Before You Book

Some historians hate it.

They argue that it adds a layer of "guesswork" that ruins the integrity of the original artifact. If we don’t know the exact shade of a soldier’s tunic, we’re making an aesthetic choice, not a historical one. But on the flip side, color makes the past feel human. It’s harder to dismiss the suffering of a person in a 100-year-old photo when their skin tone looks like yours and the grass behind them is a familiar green. It bridges the empathy gap.

The Geography of Memory

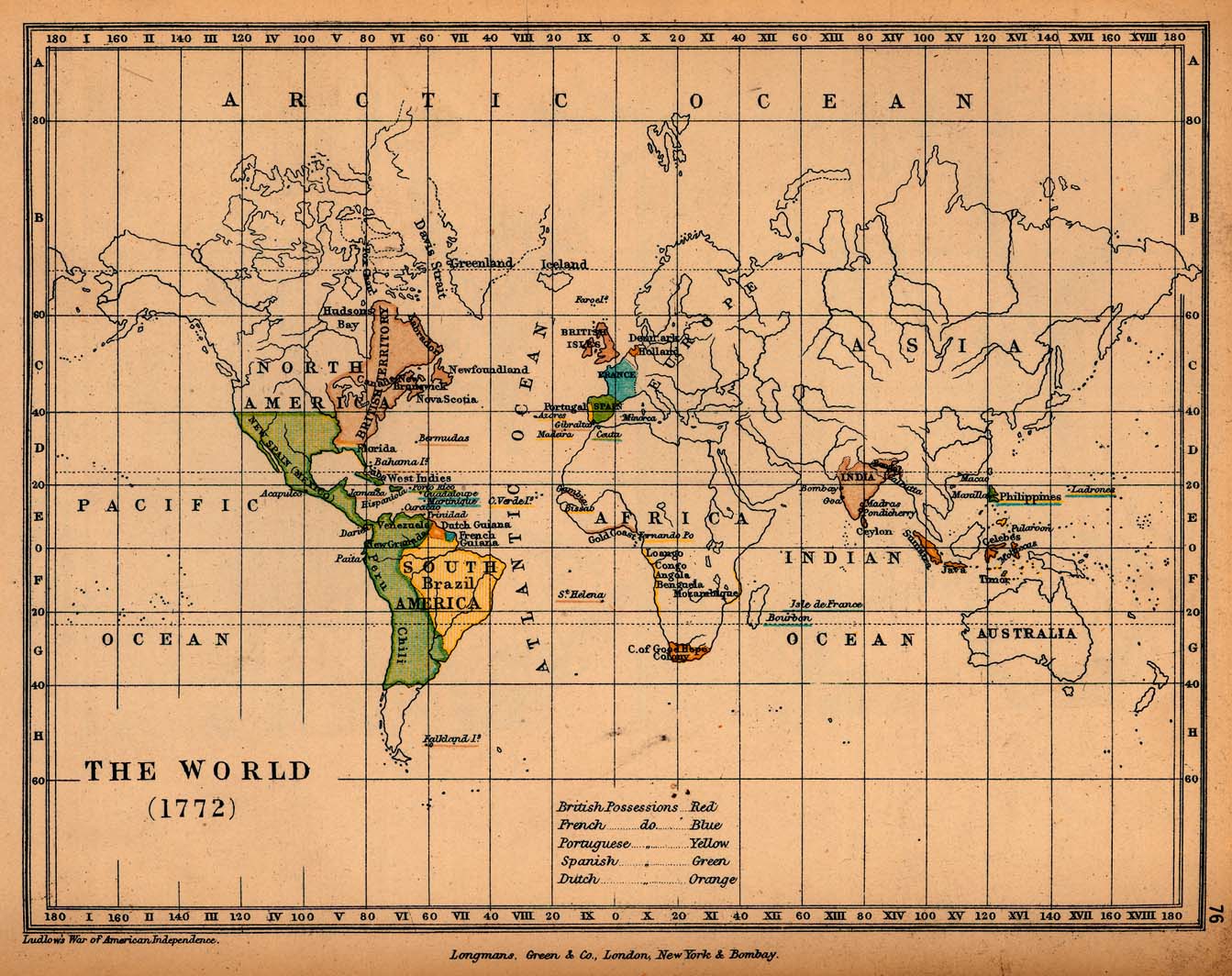

Most of the historical images of world events we see in Western textbooks are, well, Western. We have millions of photos of the liberation of Paris, but significantly fewer of the everyday lives of people in 1940s Lagos or Bangkok. This creates a visual bias where we center European and American experiences as "The World’s History."

Thankfully, archives like the Endangered Archives Programme at the British Library are working to digitize photos from across the globe. We’re finally seeing the 19th-century courts of West Africa and the early industrialization of Japan through lenses that weren't always held by colonizers. It’s a slow process of reclaiming the visual narrative.

💡 You might also like: Weather at Lake Charles Explained: Why It Is More Than Just Humidity

Real Talk: Don't Believe Your Eyes

If you find a photo online that looks too "perfect" to be old, check the grain. Look at the edges. With the rise of AI-generated "historical" photos, the market is being flooded with fakes. Real historical images of world history usually have flaws. There’s a "light leak" or a slight blur because the subject moved. If a photo from 1910 looks like it was shot on a Sony Alpha 7, it probably was—by an algorithm.

How to Actually Use These Images for Research

If you're looking into historical images of world cultures for a project or just out of curiosity, don't just look at the center of the photo. Look at the background. Look at the shoes. Look at the trash on the street. That’s where the real history is.

- Check the Metadata: If you're using digital archives like the Library of Congress or the Getty Images Archive, read the original captions. Often, the "corrected" modern caption misses the context of why the photo was taken.

- Reverse Image Search: Use Google’s "Search by Image" to see where else a photo has appeared. If it only shows up on "Creepy History" blogs and not in a museum database, be skeptical.

- Cross-Reference with Diaries: If you have a photo of a specific event, try to find a written account from the same day. The mismatch between what a camera saw and what a person felt is where the nuance lives.

Moving Beyond the Frame

The power of historical images of world significance isn't just in the "what," but the "why." Why did the photographer choose this angle? Who paid for the film? When you start asking those questions, you stop being a passive consumer of the past and start being an active researcher.

The next time you see a grainy shot of a crowded market in 19th-century Istanbul or a protest in the 1960s, remember that you're looking through a keyhole. It's a tiny slice of a massive, complicated world.

To dig deeper into authentic visual history, start by visiting the digital collections of the Smithsonian or the National Archives. Avoid the "viral" history accounts that strip away context for clicks. Instead, look for curated exhibits that explain the technical limitations and social biases of the era. The goal isn't just to see the past—it's to understand how the past wanted to be seen.

Actionable Steps for the Visual Historian:

- Verify the Source: Always trace an image back to a reputable institution like the National Archives (USA), the Imperial War Museum (UK), or university-led digital repositories.

- Contextualize the Tech: Research what kind of camera was used. Understanding that a 1900s camera required a several-second exposure helps you realize why everyone looks so stiff and "serious"—they had to stay perfectly still.

- Search for "The Unseen": Specifically look for collections focused on marginalized communities, such as the Black Archives or regional photographic societies in the Middle East and Asia, to balance the Eurocentric bias often found in mainstream historical photography.