You’ve probably seen the "Cosmic Egg" or the "Universal Man" on a random Pinterest board or a spiritual Instagram feed. They look like psychedelic posters from 1968, but they’re actually 800 years old. Hildegard von Bingen art isn't just "monastery doodles." It's a high-definition map of a woman’s consciousness, and honestly, it’s some of the most daring visual work in human history.

Hildegard was a powerhouse. She was an abbess, a composer, a scientist, and a mystic who didn't even start writing her visions down until she was 42. Imagine that. You spend four decades seeing "The Living Light," and then one day, a voice tells you to "Cry out and write!"

The Mystery of the Hand: Did She Actually Paint It?

Here is the thing that makes art historians lose sleep: we don't know for sure if Hildegard held the brush.

Basically, the scholarly world is split. Some think she sat there with her monks and nuns, directing every single pigment choice like a movie director. Others, especially modern German scholars, argue she was just the "author," and the actual painting was done by anonymous professional illuminators in her scriptorium.

But look at the Scivias manuscript—the famous Rupertsberg Codex. The imagery is so weird, so specific, and so tied to her personal metaphors that it’s hard to imagine she wasn't breathing down the artist's neck. There’s a famous self-portrait of her at the beginning of Scivias. She’s sitting with a wax tablet, and these literal "tongues of fire" are coming down from the ceiling into her eyes. It’s not subtle.

Why the Colors Look So Weird

Hildegard’s palette wasn't just about what looked pretty. She used a specific "theological color theory."

📖 Related: Bridal Hairstyles Long Hair: What Most People Get Wrong About Your Wedding Day Look

- Green (Viriditas): This was her obsession. It’s the "greening power" of God. If it’s green in her art, it’s alive, growing, and holy.

- Red: Usually represents the "Zeal of God" or the fire of the Holy Spirit.

- Gold and Silver: She used actual metallic pigments to show things that weren't of this world.

The Migraine Theory: A "Scientific" Explanation?

If you talk to a neurologist about Hildegard von Bingen art, they’ll probably mention Oliver Sacks. In the late 20th century, Sacks and other scientists suggested that Hildegard’s visions were actually "scintillating scotomas"—a fancy word for migraine auras.

The evidence? Those jagged, "fortification" patterns you see in her illuminations. The bright, shimmering stars that seem to "fall" into water. The intense, blinding light. These are all classic symptoms of a massive migraine.

Does that make her a "fake" mystic? Sorta depends on who you ask. For Hildegard, the physical pain and the spiritual insight were the same thing. She didn't see the migraine as a "bug" in her brain; she saw it as the "window" through which God spoke. Whether it was a neurological fluke or a divine download, the result is the same: art that looks like nothing else from the Middle Ages.

Breaking Down the Big Three Manuscripts

Hildegard didn't just make one book. She had a whole "Visionary Cinematic Universe" going on.

1. Scivias (Know the Ways)

This is the big one. It has 35 illustrations, including the "Cosmic Egg." Fun fact: the original manuscript disappeared during World War II. It was moved to Dresden for safekeeping and... poof. Gone. Thankfully, nuns at the Eibingen Abbey made a hand-painted facsimile right before the war (between 1927 and 1933), so we still know exactly what it looked like.

👉 See also: Boynton Beach Boat Parade: What You Actually Need to Know Before You Go

2. Liber Divinorum Operum (Book of Divine Works)

If Scivias is the prequel, this is the epic finale. The Lucca Manuscript (held in Italy) is the only illustrated version of this work. It contains the "Universal Man," which honestly makes Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man look a bit basic. Hildegard’s version has a man standing in the center of the universe, surrounded by winds, stars, and animals representing the elements.

3. Liber Vitae Meritorum (Book of Life's Merits)

This one is more about the struggle between virtues and vices. It’s less "cosmic" and more "psychological," dealing with how humans choose between good and evil.

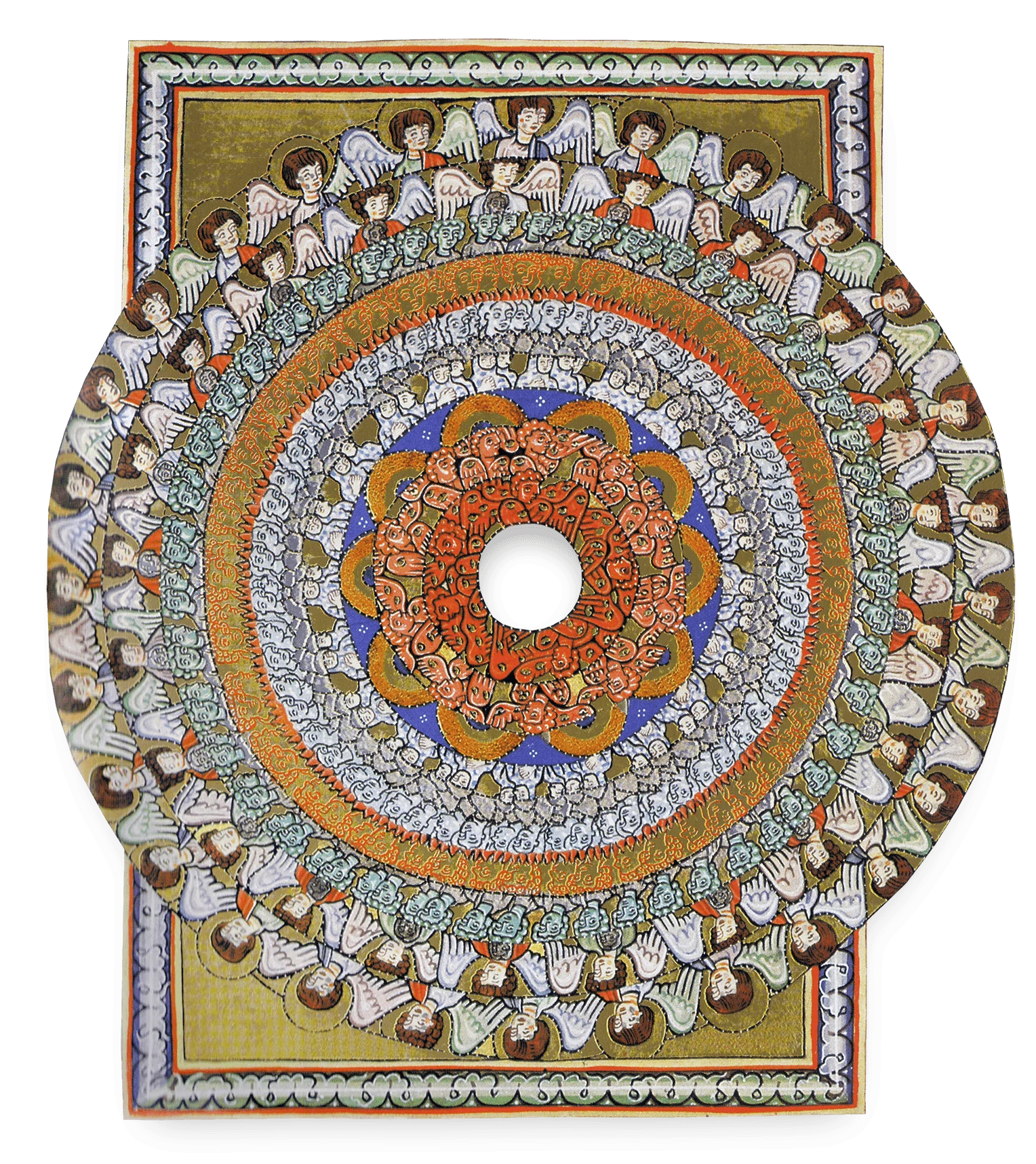

The "Cosmic Egg" and the Geometry of the Soul

In Vision Three of Scivias, Hildegard describes the universe as an egg. It sounds strange, but her reasoning was deep. An egg has layers—the shell, the white, the yolk.

She saw the cosmos as a series of concentric circles of fire, air, and water. At the very center? That’s us. Humans.

But we aren't just sitting there. In Hildegard’s worldview, every time a human breathes or thinks, it affects the "winds" of the cosmos. It’s a literal feedback loop. If we are "green" and healthy, the earth stays green. If we are "dry" and bitter, the world withers. It’s a 12th-century version of the Butterfly Effect.

✨ Don't miss: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

How to Actually Experience Hildegard's Art Today

You don't need a time machine, but you do need to know where to look. Most of the "original" original stuff is gone or locked in high-security vaults, but the digital age has been good to Hildegard.

- Digital Archives: The University of Heidelberg has a fully digitized 12th-century copy of Scivias. You can zoom in until you see the cracks in the parchment.

- The Lucca Manuscript: If you’re ever in Tuscany, the Biblioteca Statale di Lucca holds the Liber Divinorum Operum.

- Abtei St. Hildegard: The nuns in Eibingen, Germany, are the modern keepers of her flame. They still study her work and sell high-quality prints of the 1930s facsimile.

Practical Steps for the Hildegard Fan

If you're looking to dive deeper into this world, don't just stare at the pictures.

- Listen while you look: Hildegard wrote music (like the Ordo Virtutum) to go with her theology. Put on some "Sequentia" or "Canticles of Ecstasy" while browsing the Scivias plates. It changes the vibe completely.

- Look for the "Fortification Patterns": Next time you look at the "Fall of the Angels" illumination, look for the zig-zag lines. Compare them to modern "Migraine Art." It’s a wild rabbit hole.

- Read the descriptions: Hildegard’s text is as vivid as her art. She doesn't just say "I saw a light." She says "I saw a great iron-colored mountain."

Hildegard von Bingen art works because it’s authentic. It wasn't made to sell or to follow a trend. It was made because a woman in a stone room 800 years ago couldn't keep the fire in her head a secret any longer.

To truly understand her work, start by viewing the digitized Rupertsberg Codex facsimile at the University of Heidelberg's online portal. Focus specifically on the Vision of the Cosmic Egg and compare it to her later Universal Man in the Lucca manuscript to see how her "microcosm" theory evolved over thirty years of visionary work.