Data is heavy. Honestly, most people think more is better, but in the world of machine learning and complex analytics, "more" is often where the rot starts. We call it higher dimensional data: toxic edge. It sounds like a sci-fi thriller title, but it’s actually a mathematical nightmare that ruins predictive models every single day.

You’ve probably heard of the "Curse of Dimensionality." It’s that classic Bellman concept from the 50s. But the "toxic edge" is a specific, modern evolution of that headache. It’s what happens when the sheer volume of features—columns in your spreadsheet, variables in your code—starts to actively poison the results.

Mathematics changes at scale. When you move from three dimensions to three hundred, space behaves... weirdly.

The Math Behind Higher Dimensional Data: Toxic Edge

In a 2D square, most of the "stuff" is in the middle. If you throw a handful of sand onto a table, most of it bunches up away from the edges. But as you add dimensions, the geometry flips. In high-dimensional space, almost all the volume of a hypercube is located near its surface.

Think about that for a second.

If all your data points are drifting toward the "edges" of your mathematical space, they are becoming outliers by definition. This is the higher dimensional data: toxic edge. Distances between points start to become meaningless. In a high-dimensional neighborhood, the distance to your "nearest" neighbor is almost the same as the distance to your "farthest" neighbor.

Everything becomes far away.

💡 You might also like: How to See Private Instagram Profiles: Why Most Methods Are Just Scams

Everything becomes isolated.

When everything is an outlier, nothing is. Your model looks for patterns that aren’t there because it’s trying to connect dots that are light-years apart in hyperspace. It’s like trying to find a constellation in a sky where every star is a million miles from the next. You'll see a dragon if you look hard enough, but it’s just noise.

Why Your Neural Networks Are Hallucinating Patterns

Overfitting is the most common symptom of the higher dimensional data: toxic edge. If you give a model enough variables, it will eventually find a way to "solve" the training data perfectly.

It cheats.

Imagine I’m trying to predict if you’ll buy a coffee tomorrow. If I have five variables—time you woke up, weather, day of the week, bank balance, and last purchase—I might get a decent prediction. Now imagine I have 10,000 variables, including the exact barometric pressure in Tokyo and the color of the shirt worn by a random person in Oslo.

The model will find a mathematical link between that shirt in Oslo and your latte.

It’s a false correlation. It’s toxic.

Real-world experts like Trevor Hastie and Robert Tibshirani have written extensively about this in The Elements of Statistical Learning. They highlight that as the number of features $p$ approaches the number of observations $N$, the risk of finding "ghost" patterns skyrockets. This is exactly what’s happening in modern genomics and high-frequency trading. You have too many columns and not enough rows.

The "edge" is where the model falls off the cliff of reality.

The Signal-to-Noise Ratio is Bottoming Out

Data isn't just numbers. It’s a signal.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Number of Days Between Dates: Why Your Math Is Probably Wrong

When we talk about higher dimensional data: toxic edge, we’re talking about the point where the noise becomes so loud you can’t hear the music. In low dimensions, noise is a nuisance. In high dimensions, noise is the atmosphere.

Take facial recognition technology.

Early systems struggled because they looked at raw pixels—thousands of dimensions. Modern systems use dimensionality reduction (like PCA or autoencoders) to squash those thousands of pixels down into a few dozen "latent" features. They are literally fighting the toxic edge by throwing away 99% of the data.

Because most of that data is garbage.

Real-World Casualties of the Toxic Edge

Let's look at finance. Quants love data. They ingest everything. But during the "Flash Crash" scenarios or the 2008 meltdown, many models failed because they were tuned to a high-dimensional environment that assumed historical correlations would hold.

The models were living on the toxic edge.

They saw patterns in the noise of the housing market that suggested stability. They didn't see the systemic rot because they were over-indexed on micro-variables that didn't matter. They were looking at the trees and missing the forest, but also looking at the moss on the trees and the bugs on the moss.

Another example: Personalized medicine.

Researchers often look at thousands of genes (features) for only a few hundred patients (samples). This is the "Large $p$, Small $n$" problem. It is the textbook definition of the higher dimensional data: toxic edge. Many early studies in gene expression were later debunked because the "findings" were just mathematical artifacts of high-dimensional space. The "significant" genes were just the ones that happened to line up by pure chance.

How to Fight Back (Without Deleting Everything)

You can't just stop using big data. That's not how the world works anymore. You have to navigate the edge without falling over.

Regularization is your best friend. Techniques like LASSO (L1 regularization) or Ridge (L2 regularization) are essentially "penalties" for complexity. They tell the model, "Hey, if you want to use that variable about the guy in Oslo, it better be incredibly important, or I'm going to zero it out." It forces the model to be simple. Simple models survive the toxic edge. Complex ones die there.

Feature Selection. Be ruthless. Don't just dump every JSON field into your training set. If a variable doesn't have a logical, causal link to the outcome, think twice. Is it a feature, or is it just more toxic weight?

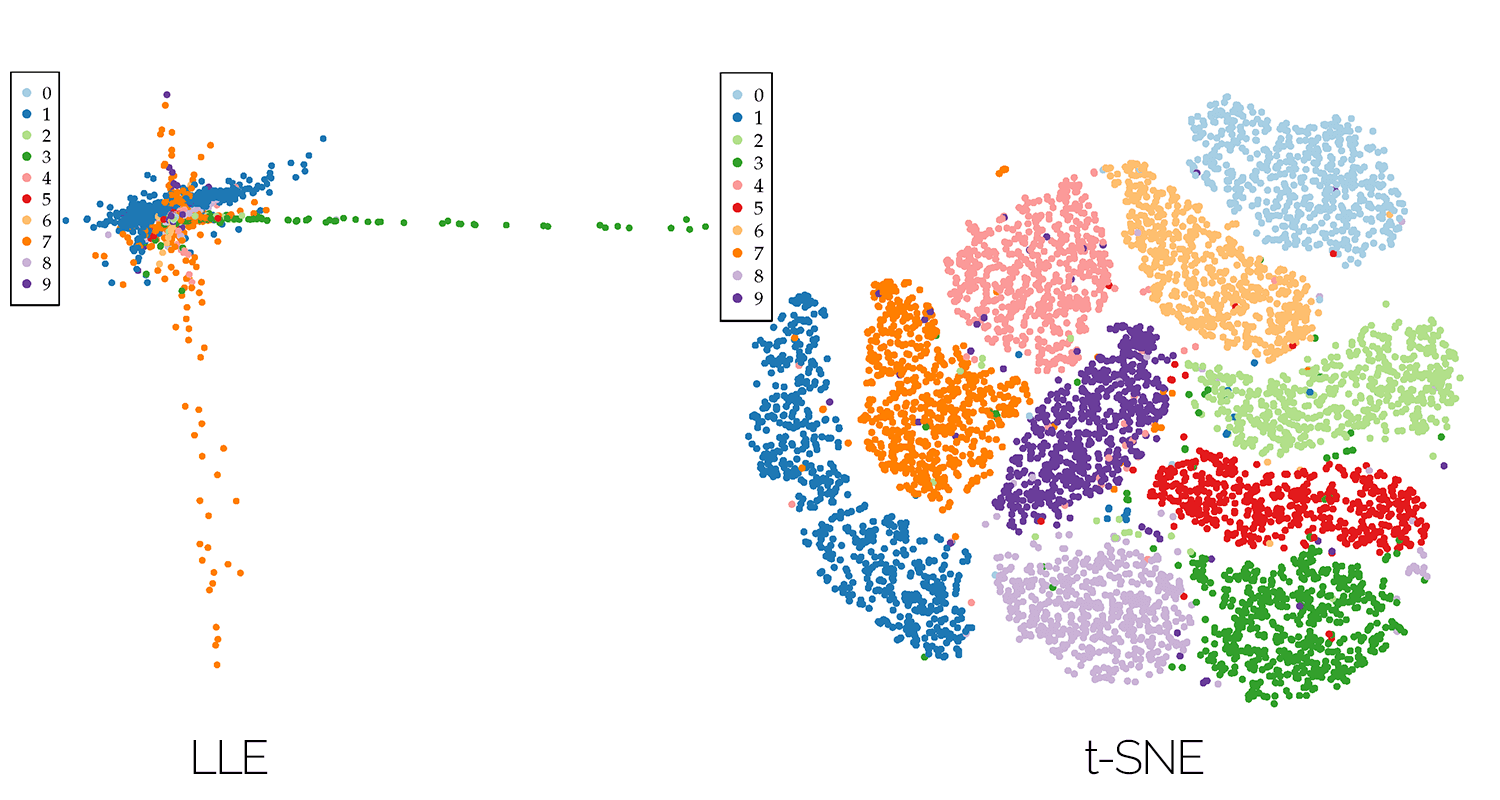

Manifold Learning. This is the idea that even though your data exists in 1,000 dimensions, it actually "lives" on a much lower-dimensional surface. Tools like t-SNE or UMAP help visualize this. They try to find the "shape" of the data within the chaos.

The Intuition Gap

The hardest part about dealing with higher dimensional data: toxic edge is that humans are bad at it. We can't visualize four dimensions, let alone four hundred. Our intuition says "more data = more information."

Mathematically, that’s a lie.

Beyond a certain point, more data = more ambiguity.

Think of it like a flashlight. In a small room (low dimensions), a flashlight illuminates everything clearly. In a massive, dark warehouse (high dimensions), that same flashlight barely reaches the walls. Everything in the distance looks like a shadow. Those shadows are the toxic edge. They look like shapes, but they're just an absence of light.

✨ Don't miss: The 23 and me dna kit: What You’re Actually Getting (and What You’re Not)

Moving Toward Sparse Solutions

The future of data science isn't about "Big Data"—it’s about "Wide Data" vs "Deep Data."

The "toxic edge" is specifically a problem of "Wide Data." We are seeing a shift toward "Sparsity." This is the mathematical assumption that only a few things truly matter. In a sea of 10,000 variables, maybe only 12 actually drive the outcome.

Identifying those 12 is the job.

If you aren't actively trying to reduce your dimensionality, you're likely building a model that will break the moment it hits the real world. Real-world data is messy. It doesn't follow the perfect, "edged" patterns your model found in the training lab.

Actionable Next Steps for Data Practitioners

If you suspect your project is suffering from the higher dimensional data: toxic edge, don't panic. Start by checking your feature-to-row ratio. If you have more columns than rows, you are already in the danger zone.

Prune the forest. Run a basic correlation matrix. If two variables are 95% correlated, you don't need both. Throw one away. It’s redundant and it’s adding to the dimensionality without adding information.

Validate like a cynic. Use K-fold cross-validation, but be extra careful about "data leakage." In high-dimensional spaces, it is incredibly easy for the answer to "leak" into your features in ways that aren't obvious. If your model's accuracy looks too good to be true (like 99.9%), it’s probably just the toxic edge giving you a false sense of security.

Check your distances. Calculate the distribution of pairwise distances between your points. If the distribution is very narrow—meaning the "closest" point and the "average" point are basically the same distance away—your high-dimensional space has collapsed. Your model is literally guessing.

Stop adding features. Start subtracting.

The most robust models aren't the ones that see everything; they are the ones that know what to ignore. High-dimensional data is a powerful tool, but the "toxic edge" is the tax you pay for that power. Pay it early by simplifying your model, or pay it later when your predictions fail in production.

The goal isn't to live on the edge. It's to stay far enough away from it that you can still see where you're going.