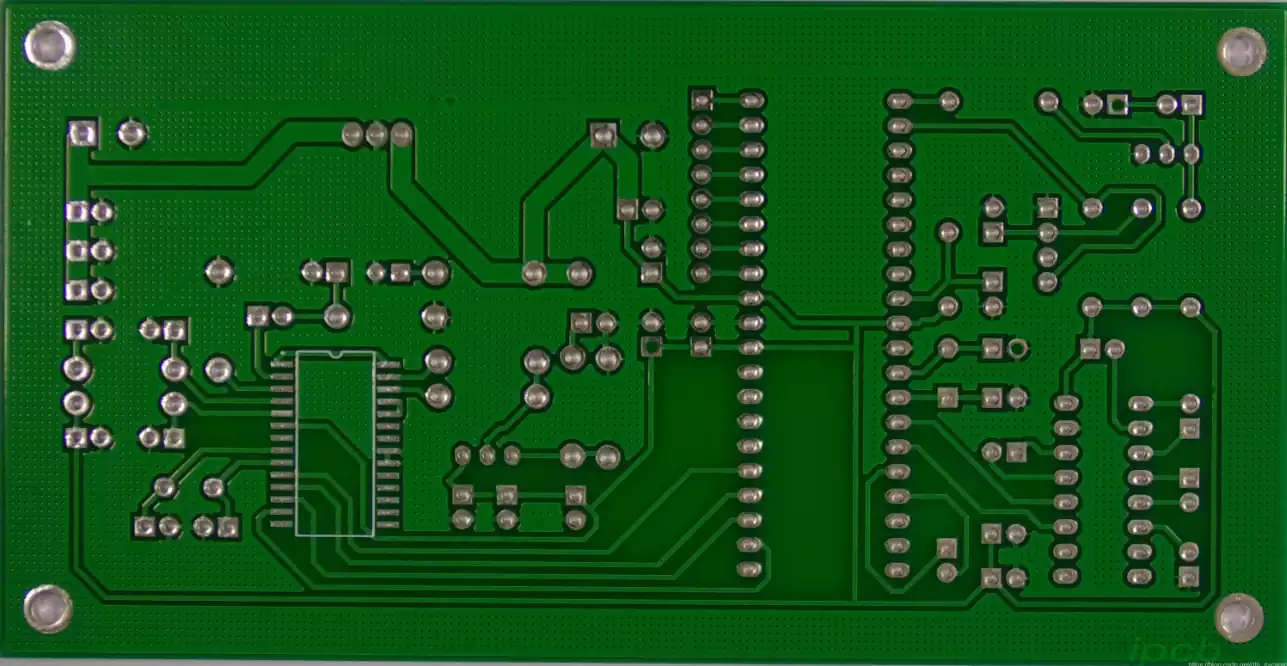

Signals move fast. Too fast, sometimes. When you’re dealing with high speed pcb design radiocord technologies, you aren't just laying down copper tracks on a piece of fiberglass anymore. You’re building a complex network of waveguides. If you treat a 10GHz signal like a simple DC circuit, your board won't just perform poorly—it basically won't work at all.

I’ve seen engineers pull their hair out because a prototype looked perfect in the CAD tool but turned into a literal radio transmitter the second they powered it up in the lab. It’s frustrating.

Radiocord Technologies has carved out a specific niche here because they tackle the stuff most people ignore: the physics of the substrate itself. High-speed design is honestly about 20% routing and 80% managing electromagnetic fields. If you don't respect the physics, the physics will punish you.

The Impedance Nightmare Nobody Mentions

Most designers talk about 50 ohms like it’s a magic number. It isn't. It’s a compromise. The real challenge with high speed pcb design radiocord technologies is maintaining that impedance across every single millimeter of the trace.

Think about a via. It looks like a simple hole. To a high-frequency signal, that via is a massive roadblock of parasitic capacitance. Radiocord emphasizes the use of back-drilling to remove the unused "stub" of the via. If you leave that stub there, it acts like a tiny antenna, reflecting energy back to the source and ruining your eye diagram.

✨ Don't miss: Why Everyone Is Looking for an AI Photo Editor Freedaily Download Right Now

Reflection is the enemy. When a signal hits a mismatch, it bounces. You get ringing. You get overshoot. If your rise times are in the picosecond range, even a tiny 90-degree bend in a trace can cause a localized impedance shift. This is why you see those smooth, curved traces or 45-degree miters in high-end RF boards.

Stackup is Everything

You can't just pick a 4-layer default and hope for the best. Radiocord’s methodology often focuses on the "ground sandwich." You want your high-speed signals tightly coupled to a continuous reference plane.

- Distance matters: The closer the trace is to the plane, the smaller the loop area.

- Dielectric constant (Dk): Standard FR-4 is kinda trash for high frequencies. Its Dk varies too much with frequency and temperature.

- Dissipation Factor (Df): This is where you lose power. If your Df is high, your signal gets sucked into the board material and turned into heat.

High-performance materials like Rogers or Isola are staples in this world. They have a stable Dk and a very low Df. Using these materials is more expensive, sure, but it’s cheaper than spinning a board four times because your signal integrity is shot.

Cross-Talk and the 3W Rule

Wires "talk" to each other. When you have two traces running parallel, the magnetic field from one induces a current in the other. It’s called crosstalk.

🔗 Read more: Premiere Pro Error Compiling Movie: Why It Happens and How to Actually Fix It

Basically, you need space. The industry standard is the 3W rule—the distance between traces should be three times the width of the trace. But honestly? In dense designs, you can’t always do that. That’s where Radiocord’s specific routing techniques come in, using guard traces or differential signaling to cancel out the noise.

Differential pairs are a lifesaver. By sending two opposite signals, any noise picked up from the outside affects both equally. The receiver only looks at the difference, so the noise gets canceled out. But you have to keep them "tight." If one trace in the pair is longer than the other (skew), the whole advantage disappears.

The Thermal Reality of Radiocord Designs

High speed usually means high power. High power means heat.

I’ve seen boards warp because the thermal expansion of the copper didn't match the substrate. Radiocord technologies focus heavily on thermal vias—stitching multiple layers together to pull heat away from the chips and dump it into the ground planes.

💡 You might also like: Amazon Kindle Colorsoft: Why the First Color E-Reader From Amazon Is Actually Worth the Wait

If you ignore the thermal profile, your clock speeds will throttle. Or worse, the solder joints will fatigue over time and crack. It’s a slow death for hardware.

Practical Steps for Your Next Build

Stop guessing. If you are moving into the realm of high speed pcb design radiocord technologies, you need to change your workflow immediately.

- Simulate early. Don't wait for the physical board. Use tools like Ansys or Altium’s signal integrity simulators to check for reflections before you hit "order."

- Talk to your fab house. Ask them about their impedance control capabilities. If they can’t give you a TDR (Time Domain Reflectometry) report, find a new vendor.

- Prioritize the stackup. Define your layers before you place a single component. Ground should be your best friend.

- Length matching is non-negotiable. For DDR or PCIe interfaces, the timing budget is so tight that even a few millimeters of difference can cause bit errors.

- Watch the returns. Every signal has a return current. It wants to follow the path of least inductance (usually right under the trace). If you cut a hole in your ground plane, that return current has to go around it, creating a giant EMI loop.

High-speed design is a discipline of details. It’s about understanding that a piece of copper is an inductor, a gap is a capacitor, and the air around the board is part of the circuit. Master the physics of high speed pcb design radiocord technologies, and your hardware will actually do what it’s supposed to.