You’ve probably seen the meteorologist on the local news pointing at a map covered in giant blue "H" and red "L" symbols. Most people just glance at them and think, "Okay, sun or rain." But there is a massive, invisible tug-of-war happening miles above your head that dictates everything from why your joints ache before a storm to why the wind won't stop howling through your window frame.

Air is heavy. It doesn't feel like it because we live at the bottom of it, but the atmosphere is literally pressing down on you with about 14.7 pounds of force per square inch. That’s the baseline. When that weight shifts—even by a tiny fraction—the world outside changes. High and low pressure are basically just descriptions of how much air is stacked above a specific spot on the Earth's surface.

Think of it like a crowd of people. In a high-pressure zone, everyone is packed tight, moving slowly, and things are generally calm. In a low-pressure zone, it’s a mosh pit. Things get messy fast.

The Invisible Weight: Understanding High and Low Pressure

To get why this matters, you have to understand that air is a fluid. It flows. It’s constantly trying to find a balance, moving from where there’s "too much" (high pressure) to where there’s "not enough" (low pressure). This movement is what we call wind.

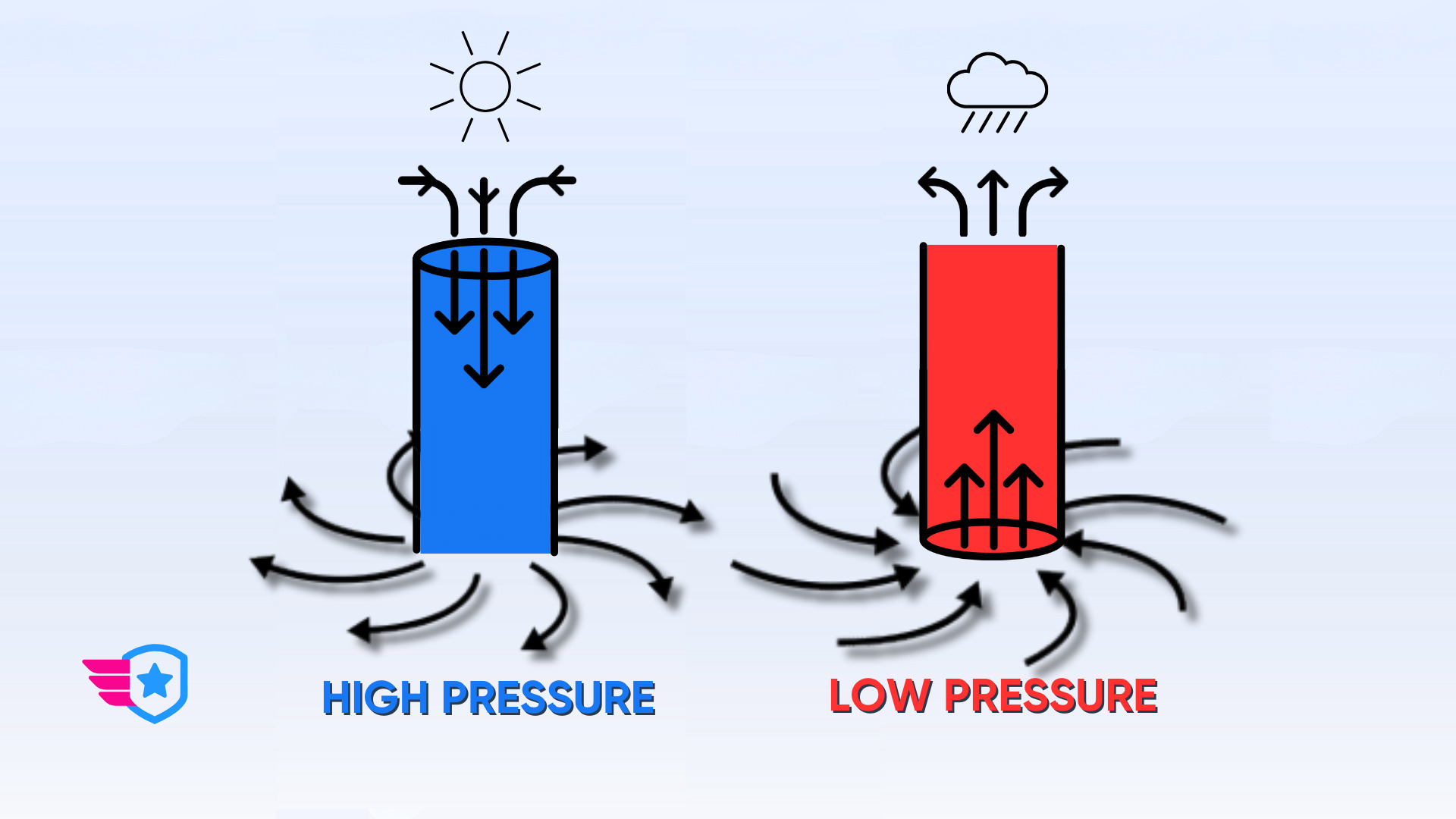

High pressure, or an anticyclone, happens when air sinks. As air cools in the upper atmosphere, it becomes denser and heavier. It starts to drop toward the ground. Because it’s sinking, it pushes down harder on the surface. That’s your "H." This sinking motion actually prevents clouds from forming. Why? Because as air sinks, it warms up, and warm air can hold more moisture as invisible vapor rather than letting it condense into water droplets. This is why high-pressure days are usually those gorgeous, blue-sky afternoons where nothing seems to happen.

✨ Don't miss: Wait, is that a Snake Egg? What to Look for in Pics of Snake Eggs and Why You Might Be Mistaken

Low pressure is the polar opposite. It’s an "unstable" situation. Here, air is rising. Maybe the ground is warm, heating the air above it, or maybe two different air masses are colliding and forcing the air upward. As that air rises, it cools. Since cold air can't hold as much water vapor as warm air, that moisture turns into clouds, then rain, then maybe a thunderstorm or a blizzard.

Why the Wind Swirls

If the Earth stood still, air would just blow in a straight line from high to low. But we’re spinning. Thanks to the Coriolis Effect, air in the Northern Hemisphere curves to the right.

This creates a specific "look" on the weather map:

- High Pressure: Air moves clockwise and outward. It’s like a fountain of air spilling onto the ground and spreading out.

- Low Pressure: Air moves counter-clockwise and inward. It’s like a vacuum cleaner sucking air toward the center and pulling it upward.

If you’re standing outside and the wind is hitting your back, the low-pressure center is usually to your left. It’s a handy trick if you’re ever stuck without a smartphone and need to know where the storm is headed.

How High and Low Pressure Mess With Your Body

It isn't just about the rain. Have you ever noticed your knees or lower back hurting right before a big storm? That isn't just an old wives' tale. It's physics.

When a low-pressure system moves in, the weight of the atmosphere on your body literally decreases. This allows the tissues in your joints to expand slightly. If you have chronic inflammation or old injuries, that tiny bit of expansion puts pressure on your nerves. Boom. You’re a human barometer.

According to Dr. Robert Newlin Jamison, a professor at Harvard Medical School who has studied the link between weather and pain, it’s the change in pressure that does it. Your body likes equilibrium. When the outside pressure drops rapidly, the internal pressure in your joints is suddenly higher than the air around you.

The Real-World Stakes: Why "L" Means Trouble

When we talk about extreme weather, we are almost always talking about "deep" low pressure. The lower the pressure drops, the more violent the weather gets.

Take a hurricane, for example. The eye of a hurricane is a zone of incredibly low pressure. Hurricane Wilma in 2005 holds the record for the lowest pressure ever recorded in the Atlantic basin at 882 millibars. For context, "normal" sea-level pressure is around 1013 millibars. That massive "hole" in the atmosphere sucks in air with such force that it creates the 150+ mph winds that level cities.

On the flip side, high pressure can be dangerous too, just in a quieter way. Strong high-pressure systems can lead to "heat domes." During the 2021 Pacific Northwest heatwave, a massive high-pressure ridge parked itself over the region. It acted like a lid on a pot, trapping hot air and compressing it, which made it even hotter. Lytton, British Columbia, hit 121°F because the high pressure wouldn't let the heat escape.

The Feedback Loop

Weather is rarely just one thing happening in isolation. High and low pressure systems are parts of a global conveyor belt.

Imagine the Jet Stream. It’s a river of fast-moving air high in the atmosphere. It acts like a border between cold air from the poles and warm air from the tropics. When the Jet Stream "dips" south, it creates a trough. This is where low-pressure systems love to form. When it "bulges" north, it creates a ridge, which is high-pressure territory.

- The Trough: Expect rain, wind, and a drop in temperature.

- The Ridge: Expect sunshine, calm winds, and rising temperatures.

If you’ve ever wondered why your flight from New York to London is faster than the return trip, it’s because the pilots are using these pressure-driven wind currents to hitch a ride.

Identifying Pressure Changes Without a Map

You don't need a degree in meteorology to see high and low pressure at work. Honestly, just look at the sky.

If you see high, wispy "mare's tail" clouds (cirrus clouds), a low-pressure system might be 24 to 48 hours away. These are the vanguard. They’re the very top of the rising air from an approaching storm.

Is the smoke from your neighbor's chimney rising straight up? That’s high pressure—the air is stable and heavy. If the smoke is curling downward or hanging low to the ground (what sailors call "smoky water"), pressure is likely dropping.

Another tell: Sound. Low pressure often makes distant sounds—like a train whistle or a highway—sound much louder and clearer. This happens because the clouds associated with low pressure can create a "ceiling" that reflects sound waves back toward the ground instead of letting them dissipate into space.

Living With the Barometer: Practical Steps

Understanding the pulse of the atmosphere actually helps with daily planning. It’s more than just "should I bring an umbrella?"

🔗 Read more: Finding the Perfect Pic of Forget Me Nots: Why These Tiny Blue Flowers Are Harder to Shoot Than You Think

If you’re a gardener, pay attention to high pressure in the winter. Those clear, star-filled nights with no wind are when frost is most likely to kill your plants. Without a "blanket" of clouds (which you’d get with lower pressure), all the heat from the Earth escapes into space.

For the hikers and pilots, low pressure means "thin" air. Even though the air is rising, it’s less dense. This means your car engine might feel slightly more sluggish, and you’ll get winded faster on a mountain trail.

Actionable Insights for Weather Changes:

- Monitor Rapid Drops: If your smartwatch or home barometer shows a drop of more than 1 millibar per hour, a significant storm is likely within 3-6 hours. Secure loose patio furniture.

- Manage Joint Pain: If you’re prone to barometric pain, stay hydrated and keep your joints warm when the pressure starts to dive. Compression sleeves can sometimes help counteract the internal tissue expansion.

- Check Tires: Air pressure in your tires changes with the atmospheric pressure and temperature. After a major high-pressure "cold snap," your "low tire pressure" light is almost guaranteed to turn on.

- Watch the Clouds: Learn the difference between "fair weather cumulus" (the fluffy cotton balls) and "cumulonimbus" (the towering anvils). The latter means the low-pressure "updraft" is becoming violent.

Nature is basically a giant balancing act. High pressure tries to fill the gaps, and low pressure tries to vent the heat. We’re just caught in the middle of it. By keeping an eye on these shifts, you’re not just looking at a forecast; you’re understanding the physical mechanics of the planet.